Contraceptive Self-Care: The ability of individuals to space, time, and limit pregnancies in alignment with their preferences, with or without the support of a healthcare provider

What is the program enhancement that can intensify the impact of High Impact Practices in Family Planning?

Integrate contraceptive self-care into family planning and reproductive health services and systems.

Background

Self-care is defined as the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote and maintain health, prevent disease, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a healthcare provider.1,2 Ranging from access to preventive and curative products over the counter, to education around preventive health behaviors and treatment, to the development of self-care technologies that put control in the user’s hands, self-care has evolved into an important approach to support health and wellness.

Self-care expands access to healthcare services and supports health systems. Self-care increases choice and access, leading to better health outcomes. With growing healthcare worker shortages, disruptions from conflict and climate emergencies, and rising use of digital tools, evidence-based self-care is now more essential than ever.3–7 Recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO), self-care plays a critical role across a range of health areas including mental health, HIV, and reproductive health.2,8–10 Self-care also supports management of diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic conditions.11,12

Contraceptive self-care is the ability of individuals to freely and effectively space their pregnancies, time their pregnancies, and prevent pregnancies in alignment with their fertility preferences, with or without the support of a healthcare provider. This is facilitated by the integration of contraceptive self-care interventions into policies, programs, and delivery channels across health systems.

Contraceptive self-care is a key component in improving access to contraceptive care and promoting client empowerment.13 It also can help women who are subjected to intimate partner violence and reproductive coercion in using contraceptives discreetly and safely.14,15 At least 18 low- and middle-income countries have integrated a form of contraceptive self-care into their sexual and reproductive health policy.6,16,17 Evidence supports the positive influence of contraceptive self-care, bolstering the impact of family planning programming by improving implementation or reach with improvement in method uptake and continuation, increased service delivery, and access by clients.

Approaches to contraceptive self-care encompass a range of technologies, practices, delivery channels, and social and behavior changes to facilitate greater control over one’s reproductive health. Examples of evidence-based contraceptive self-care interventions can include18* :

|

|

Contraceptive self-care offers the broad positive attributes of self-care approaches, including improvements in access and equity, increases in personal agency, enhanced confidentiality, reduced costs to clients and the health system, and a partial answer to shortages in the healthcare workforce.7 Deliberate social and systems changes made to integrate contraceptive self-care can strengthen the health system, fulfill contraceptive demand, and support method continuation.7,19** In times of political, economic, climate, or epidemic/pandemic upheaval, contraceptive self-care can provide increased access and resources and added options in contraceptive decision making. The suspension of clinical services at facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic provided a wake-up call toward the need for self-care.20,21 Community-based self-care programming, including the work of community healthcare workers, facilitated access for clients during pandemic and humanitarian emergency settings.19,22

Like self-care approaches more broadly, contraceptive self-care must sit firmly within the health ecosystem and include essential connections and accountability across both public and private channels of the health system. “Assessing and ensuring an enabling environment in which self-care interventions can be made available safely and appropriately must be the cornerstone of any strategy to introduce or expand use of these interventions.”23 Contraceptive self-care must align with client safety, information, choice, continuity of care, and other overall quality standards for contraceptive services and products.24 Successful implementation of contraceptive self-care requires effort across all six of the WHO health systems building blocks (Figure 1).25,26

* The literature is rich with studies on condom use for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections and HIV and for contraception. Studies on condom use are hard to disentangle between STIs/HIV and contraceptive use. Thus, this brief focuses on other self-managed methods.

** Note: Studies cited in this brief focus on a limited range of available self-care methods.

| Health Information Systems | Service Delivery | Access to Essential Medicines | Health Workforce | Financing | Leadership/Governance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data generation, compilation, analysis, and communication. Include self-care data integration into national health or logistics management information systems. Information related to self-care shared with policymakers, program managers, healthcare workers, and communities. |

Comprehensive range of service delivery approaches, regulatory systems, and trained healthcare workers to support self-care. Includes peer support, counseling, training, referral, community support, and digital health approaches. | Access to registered essential medicines and medical products and technologies of ensured quality, safety, and efficacy to be used in self-care. Includes national policies, dispensing protocols, standards, and guidelines and regulations, as well as prices and quality. | Healthcare workers, including pharmacists and community healthcare workers, trained in self-care approaches and provide a high standard of care that promotes and supports self-care option. | Money and cost-related issues can affect whether people have fair access to affordable self-care options. | Strategic policy frameworks and service delivery guidelines exist for self-care and are combined with effective oversight, coalition building, and regulation, with attention to system design, accountability, and environmental considerations. |

Adapted from: World Health Organization. Implementation of Self-Care Interventions for Health and Well-Being: Guidance for Health Systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/378232/9789240094888-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Theory of Change

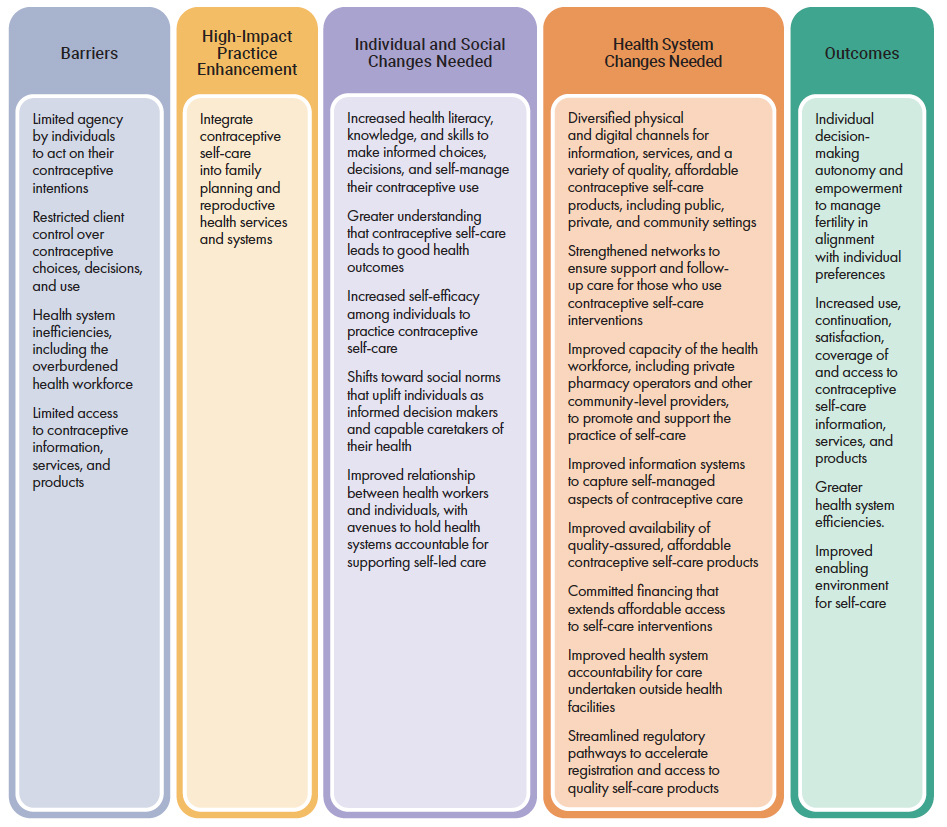

As the basis for planning, ongoing decision making, resources, and action, the contraceptive self-care theory of change (Figure 2) illuminates how self-care can overcome obstacles by addressing individual, social, and health system barriers to ultimately improve outcomes for women.

Theory of Change

How can this practice enhance HIPs?

Contraceptive self-care is an enhancement to the High Impact Practices. An enhancement is a practice that can be implemented in conjunction with HIPs to further intensify their impact. HIPs fall into three categories—enabling environment, service delivery, and social and behavior change—and contraceptive self-care enhances HIPs within each of those categories.

The impact of evidence-based HIPs is boosted through contraceptive self-care (Figure 3). Self-care interventions affect every HIPs category, strengthening the implementation impact across the HIPs categories. For more information on HIPs, see https://fphighimpactpractices.org.

| HIPs Category and Practice Examples | HIPs when combined with Contraceptive Self-Care | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Enabling Environment

Comprehensive Policy Processes: The agreements that outline health goals and the actions to realize them |

Clear and actionable policies, regulations, and service delivery guidelines for contraceptive self-care lead to higher fulfillment of contraceptive demand.

Successful implementation of contraceptive self-care requires development, implementation, and monitoring of self-care policies and regulations. |

Improved implementation of contraceptive self-care through health system accountability and strategic and systematic enactment.

Strong policies, regulations, and guidelines for contraceptive self-care, that when implemented, lead to increased access, use, and continuation of contraceptive methods. |

| Service Delivery

Community Health Workers: Bringing family planning services to where people live and work Pharmacies and Drug Shops: Expanding contraceptive choice and access in the private sector |

Community-based support, information, supplies, and service delivery by community healthcare workers and pharmacies/drug shops facilitate contraceptive self-care, including high-quality counseling and self-care training. | Reduces burden on the health system through provider ability to serve more clients. Provides clients with increased access to contraceptive methods, self-care behavioral support, and a robust referral system in client-preferred settings, which improves contraceptive uptake, satisfaction, and continuation. |

| Social and Behavior Change

Knowledge, Beliefs, Attitudes, and Self-Efficacy: Strengthening an individual’s ability to achieve their reproductive intentions Social Norms: Promoting community support for family planning Digital Health for Social and Behavior Change: New technologies, new ways to reach people |

Contraceptive self-care incorporated into community efforts in social messaging, support, and ultimately individual behavior change; enhances agency to act on contraceptive intentions.

Digital health approaches in combination with contraceptive self-care interventions can provide access to digital money (online, noncash funds), reporting and logistics, data collection around use of contraceptive self-care, and training for providers and referrals for clients. Digital health technology can provide immediate access for clients seeking information across all aspects of contraceptive self-care. |

Contraceptive self-care within a supportive community and healthcare system, increased knowledge, and improved attitudes lead to better communication, greater satisfaction with selected methods, consistent method use, and decreased discontinuation.13,27 Community “norms” or rules also affect decision making around family planning.28

Digital technology in family planning services can be viewed as cost-effective and well accepted by clients and providers. It can raise women’s awareness of family planning methods and side effects, support shared decision making among couples, and help address health system challenges. Digital tools can enhance the coverage and quality of family planning services.29 |

What is the influence of contraceptive self-care on family planning?

Studies show a positive influence of contraceptive self-care on family planning, which bolsters the impact of other HIPs. Examples of contraceptive self-care reinforcing gains and outcomes in family planning are elaborated in the text below.

Contraceptive self-care increases demand for contraception.

Studies have demonstrated the demand for user-managed methods and self-care options and have identified populations that are especially likely to use them. These include young and/or unmarried women, women who want to keep their sexual activity or their contraceptive use a secret, and women who have infrequent sex, including those whose husbands travel and those who had nonconsensual sex.30–32

Women living in crises and humanitarian settings, who want a short-acting method, or who lack access to health facilities because of conflict or climate emergencies, are more likely to seek and use self-managed methods.5,33

Contraceptive self-care improves method satisfaction.

Studies have demonstrated high acceptability of self-managed contraceptive methods, with women expressing high satisfaction.34 Self-perceived competence with self-injection of DMPA (depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate, also known as Depo-Provera) increases over time.35,36 It is critical that women receive support to be able to self-inject DMPA easily. Contraceptive self-care means that women have increased agency over their contraceptive decision making.

Contraceptive self-care supports contraceptive method continuation.

Multiple studies compare method continuation rates for over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription oral contraceptive users, and contraceptive injectables when administered by a provider versus a user.36,37 Evidence suggests that OTC oral contraceptive pills may have higher continuation rates than prescription pills from a health center.38 In another study, the 12-month continuation rate for women self-injecting DMPA-SC was statistically higher than for women receiving DMPA-IM from a healthcare worker. Pregnancy rates and side effects were the same for everyone.37

Contraceptive self-care increases privacy and empowers women to avoid provider bias and reduce coercion.

Contraceptive self-care can reduce provider bias as a barrier to care. For example, a woman may wish to use a DMPA-SC injectable discreetly in response to intimate partner violence or reproductive coercion; self-injection may enhance confidentiality, safety, and privacy.14,39 In short, self-injection may improve injectable continuation by reducing clinic access challenges while enhancing women’s autonomy and control over contraceptive use and improving the ability to control their own contraceptive decision making.37

Adolescents often face provider bias based on age or marital status.46 Contraceptive self-care can help address these concerns by offering greater privacy and less exposure to judgment—particularly with oral and emergency contraceptive pills accessed through pharmacies.40 Pharmacies are valued for their convenience, discretion, affordability, and respectful service. Increased privacy of contraceptive self-care has been seen as important to adolescent women utilizing pharmacies for their contraceptives.42

Contraceptive self-care saves time and money.

Contraceptive self-care reduces costs and improves efficiency for both clients and health systems. Self-care is less costly for individuals than facility-based care, as it reduces transportation expenses, user fees, wait times, and the time needed to seek and receive care.17 Contraceptive self-care offers flexibility in method, timing, and location. Studies in Uganda and Senegal show self-injection is cost-efficient when considering savings for both women and health systems.43,44 In cases where self-care can be an alternative to facility-based care, it has the potential to reduce the burden on the health system by freeing up resources and staff, thereby improving efficiencies.45

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

Institutionalize contraceptive self-care interventions through strong leadership and governance.

Health systems must recognize and support self-care beyond traditional facilities. Clear legal and policy frameworks are essential to guide both public and private sectors, ensure accountability, and simplify product approvals. The Ministry of Health should lead efforts to adopt and implement self-care, including reviewing existing laws. Contraceptive self-care should align with universal health coverage, primary healthcare, and other broader goals. Box 1 illustrates how countries are furthering access to self-care.

Adapt contraceptive self-care to local contexts.

Effective self-care interventions must be tailored to local needs and realities. Engage key stakeholders—public and private sector actors, civil society, women-led groups, and the like—from design through evaluation. Involving providers and clients, particularly adolescents, ensures that services are appropriate and acceptable. Local health teams should lead in adapting policies, building capacity, and aligning self-care with existing contraceptive options. Strengthen peer networks and mentorship to empower individuals to make informed choices.

Consider strategic, comprehensive, and multisectoral advocacy approaches to contraceptive self-care, including institutional change and provider support.

Implementing contraceptive self-care intervention approaches must include sustainable policy and program development and provider buy-in. Adapting health service innovations to changing sociocultural, economic, and institutional contexts is vital for success. Build political will to introduce and sustain contraceptive self-care interventions. Identify and recruit potential influencers to both build the system and advocate for implementation. Advocacy with reticent providers who may resist adoption of contraceptive self-care approaches is critical.

Create and employ health literacy approaches to contraceptive self-care.

Examine behavioral shifts that are needed by users and those who will support them in self-care practice. Directly address health literacy, client knowledge, and skills needed for successful contraceptive self-care approaches, creating broad awareness of self-care and improvements in client knowledge and skills, including instruction and coaching.

Train and support providers for quality self-care delivery.

Health providers, including pharmacists, need targeted training and support to deliver contraceptive self-care. Training should cover client coaching, use of guidelines and job aids, referrals, data collection, and safe product disposal. Ongoing supervision, mentoring, and refresher sessions are key. Pre-service education should include self-care methods to prepare future providers, with quality counseling as a central focus.

Plan for supply and access when scaling up contraceptive self-care.

When clients practice self-care, they often take home multiple units of a product, which affects how supplies are ordered and restocked. To support self-care, ensure that contraceptive products are widely available through multiple channels. This may require updating supply chain systems to include new distribution points. Contraceptive self-care products should be listed on the national essential medicines list to improve access and affordability. National forecasting and supply planning should reflect how these products are dispensed for self-care use.

Secure funding and resources for contraceptive self-care.

Contraceptive self-care is a cost-saving way to improve health system efficiency. Studies show it can save money while providing improved access to care for many clients. However, it needs dedicated funding to succeed. This includes training providers in both clinics and communities, offering supportive supervision, creating training materials and job aids, and sharing best practices.43,44,47 These efforts should be built into health policies and budgets. To ensure long-term success, a clear strategy for sustainable funding is essential. Financing can come from government allocations, private sector support, insurance, out-of-pocket payments, vouchers, or other sources.

Examine digital health opportunities for contraceptive self-care.

Digital technologies and platforms have expanded the use of telehealth and often resulted in expansion of self-care approaches. During the COVID-19 era, digital platforms and telehealth options grew rapidly, increasing health service access and use, including contraceptive self-care. Digital technology and telehealth are changing the landscape of service delivery by creating new ties to quality services and virtual approaches, including contraceptive self-care. Digital health and AI technologies can enable a more personalized approach to care, requiring less interaction with formal (provider-assisted) care while ensuring that care follows standards. See Digital Health HIPs to support providers, systems, and social and behavior change.

Measure and monitor contraceptive self-care effectively.

To expand contraceptive self-care, it’s important to understand how to measure its use and impact. Monitoring and evaluation help identify what’s working and where changes are needed. Because current health information systems may not capture self-care data, special tools should be developed for this purpose. Proxy measures—such as tracking how many doses are distributed or sold—can help protect users’ privacy. Collecting client feedback is also key, along with tracking how self-care is scaled and sustained. Through enhanced engagement with the private sector, surveys and data from manufacturers and other alternative nongovernmental sources may be needed. Health information systems should be updated to include self-care data and ensure fair access for all.

Box 1. Contraceptive Self-Care Moves Forward

Nigeria: Strengthening Policy. One of the first countries to adopt global guidelines (2020).2 As of 2023, 21 of the 36 Nigerian states have committed to implementing the guidelines.

India: Self-Care Kits. Self-care options and decisions put directly in the hands of women and men. Kits include condoms, emergency contraceptive pills, and a pregnancy test.

Ethiopia: Conflict Zones. Self-care approaches support sexual and reproductive health service and method delivery in northern Ethiopia and other conflict zones. Includes over-the-counter contraceptive pills, emergency contraceptives, and self-care interventions centers. Training of providers is a key component.

Uganda: Information and Education. Ministry of Health–led development of self-care informational materials and messaging to highlight self-care approaches to the public, providers, and policymakers. Dissemination is intended to increase uptake of self-care.

Implementation Measurement and Indicators

Integrating contraceptive self-care into family planning and reproductive health services and systems has demonstrated benefits in the cost and efficiency of family planning. The following indicators may be helpful in measuring implementation and outcomes:

- Percentage of women ages 15–49 reporting they are using a method that can be self-administered (disaggregated by method/practice, age, geography, and public/private). Note: This indicator will look different in each country because of varied self-care policies. Could be available from health management information systems.

- Percentage of women ages 15–49 reporting they received contraceptive self-care information from a provider in the past 12 months (disaggregated by age, geography, and public/private).

- Percentage of women ages 15–49 reporting exposure to contraceptive self-care messages on radio, television, social media, or in print in the past 12 months (disaggregated by age, geography, and source).

- Contraceptive self-care services and supplies are integrated into national costed implementation plans for program implementation plans and financing strategies.

- Status of a policy or policies that expand access to contraceptive self-care, for example, whether a policy has been adopted, implemented, or monitored that authorizes clients to self-inject DMPA-SC and allows community healthcare workers and pharmacists to initiate self-injection.

Tools and Resources

Tools and Resources

- Implementation of Self-Care Interventions for Health and Well-Being: Guidance for Health Systems. The World Health Organization offers an evidence-based perspective on interventions and actionable steps for integrating self-care, including contraceptive self-care, into national health systems, with a focus on enabling policy environments and service delivery reform.

- Self-Care Interventions for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: Country Cases. This collection of case studies showcases how diverse countries are advancing contraceptive self-care through innovative policy, programmatic, and regulatory strategies, and providing practical lessons for adaptation.

- Self-Care for Family Planning: 20 Essential Resources. This curated package of resources offers tools, guidance, and evidence for practitioners and policymakers working to operationalize contraceptive self-care across health systems.

- Sexual and Reproductive Health Self-Care Measurement Tool, First Edition. This tool discusses common dilemmas in self-care measurement and provides indicators and a measurement framework to help track progress and the impact of self-care interventions, including those related to contraceptive access and use.

- Progress and Potential of Self-Care: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead. This report synthesizes recent global progress, emerging trends, and key priorities for advancing self-care, positioning contraceptive self-care as central to rights-based, resilient health systems.

Priority Research Questions

Contraceptive self-care must exist within the health ecosystem, and many obstacles must be overcome to ultimately improve outcomes. Key research questions include:

- How can contraceptive self-care expand equitable, affordable access to quality care in health systems, including both public and private channels?

- What are the contraceptive self-care approaches that enable positive social perceptions and normalization of contraceptive self-care?

- What is the impact of self-care policies and guidelines on access to and use of contraceptive self-care?

- How does contraceptive self-care address the needs of marginalized populations, such as adolescents, those in humanitarian settings, those with disabilities?

- What is the evidence on whether contraceptive self-care contributes to a sense of empowerment, including the ability to respond to intimate partner violence and reproductive coercion?

- What strategies cost-effectively reduce bias by providers, including pharmacists, related to contraceptive self-care?

Search Strategy

To compile the list of documents meeting inclusion criteria, a literature search was conducted using bibliographic databases and hand searching of online websites for peer-reviewed articles and grey literature that includes contraceptive self-care. The period of review focused on documents published from 2010 to 2025.

For more information, download the “Methods for Literature Search, Information Sources, Abstraction, and Synthesis” document.

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Contraceptive Self-Care: The ability of individuals to space, time, and limit pregnancies in alignment with their preferences, with or without the support of a healthcare provider. Washington, DC: HIPs Partnership; August 2025. Available from https://fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/contraceptive-self-care/

Acknowledgements

This HIP enhancement brief was authored by Holly Burke (FHI 360), Maria Carrasco (USAID), Megan Christofield (Jhpiego), Jane Cover (PATH), Andrea Ferrand (PSI), Josselyn Neukom (SwipeRx), Gertrude Odezugo (USAID), Funmilola OlaOlorun (University of Ibadan, Nigeria), Sarah Onyango (PSI), Melkam Teshome-Kassa (CIFF), and HIPs writer Linda Cahaelen.

This HIPs Enhancement brief was reviewed and approved by the HIPs Technical Advisory Group. The brief benefited from critical reviews and helpful comments from those who commented via the HIPs website.

Special thanks to Gilda Sedgh, Rose Stevens, and Callie Goering for their extensive literature review and to the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation for its support.

The World Health Organization Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIPs briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception.

References

- World Health Organization. Self-Care for Health and Well-Being. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/self-care-health-interventions.

- World Health Organization. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Self-Care Interventions for Health: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/325480/9789241550550-eng.pdf.

- Boniol M, Kunjumen T, Nair TS, Siyam A, Campbell J, Diallo K. The Global Health Workforce Stock and Distribution in 2020 and 2030: A Threat to Equity and ‘Universal’ Health Coverage?. BMJ Global Health. 2022;7(6):1–8. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9237893/.

- Dawson A, Tappis H, Tran NT. Self-Care Interventions for Sexual and Reproductive Health in Humanitarian and Fragile Settings: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Services Research. 2022;22(1). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-022-07916-4.

- Tran NT, Tappis H, Moon P, Christofield M, Dawson A. Sexual and Reproductive Health Self-Care in Humanitarian and Fragile Settings: Where Should We Start? Conflict and Health. 2021;15(1). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13031-021-00358-5#citeas

- Christofield M, Moon P, Allotey P. Navigating Paradox in Self-Care. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(6):e005994. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8212175/.

- Narasimhan M, Aujla M, Van Lerberghe W. Self-Care Interventions and Practices as Essential Approaches to Strengthening Health-Care Delivery. The Lancet Global Health. 2022;11(1). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9597558/.

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline on Self-Care Interventions for Health and Well-Being, 2022 Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/357828/9789240052192-eng.pdf.

- Narasimhan M, Logie CH, Gauntley A, et al. Self-Care Interventions for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for Advancing Universal Health Coverage. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2020 July 20;28(2):1778610. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7887951/.

- Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, et al. Addressing the Burden of Mental, Neurological, and Substance Use Disorders: Key Messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd Edition. The Lancet. 2016;387(10028):1672–1685. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)00390-6/abstract.

- Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient Self-Management of Chronic Disease in Primary Care Patient Self-Management of Chronic Disease in Primary Care. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(19):2469–2475. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://phdres.caregate.net/curriculum/GeneralCurriculum/jama2k2-2469.pdf.

- Riegel B, Moser DK, Buck HG, et al. Self‐Care for the Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017;6(9). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5634314/.

- Burke HM, Ridgeway K, Murray K, Mickler A, Thomas R, Williams K. Reproductive Empowerment and Contraceptive Self-Care: A Systematic Review. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2022;29(2). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9336472/.

- Akoth C, Oguta JO, Gatimu SM. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Covert Contraceptive Use in Kenya: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11375-7.

- Uysal J, Pearson E, Benmarhnia T, Silverman J. Does Covert Contraceptive Use Increase Women’s Risk of Abuse? A Longitudinal Study in Kenya. San Diego: Center on Gender Equity and Health, UC San Diego School of Medicine; Publication Pending, 2025. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.svriforum2024.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Jasmine-Uysal-UPDATE.pdf.

- USAID. National Family Planning Guidelines in 10 Countries: How Well Do They Align with Current Evidence and WHO Recommendations on Task Sharing and Self-Care? Washington, D.C.: USAID; 2020 July. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://hrh2030program.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/HRH2030_Task-Sharing-Brief_Final_07-31-20.pdf.

- Self-Care Trailblazer Group. Costing and Financing for Self-Care for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: A Review of Evidence and Country Consultations in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in Africa. Washington, D.C.: Population Services International; 2023 September. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Costing-and-Financing-Technical-Brief-V3.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Self-Care Interventions for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights to Advance Universal Health Coverage: 2023 Joint Statement by HRP, WHO, UNDP, UNFPA, and the World Bank. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373301/9789240081727-eng.pdf.

- Malkin M, Mickler AK, Ajibade TO, et al. Adapting High Impact Practices in Family Planning During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences from Kenya, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2022;10(4). Accessed July 27, 2025. https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/10/4/e2200064.

- Haddad LB, RamaRao S, Hazra A, Birungi H, Sailer J. Addressing Contraceptive Needs Exacerbated by COVID-19: A Call for Increasing Choice and Access to Self-Managed Methods. Contraception. 2021;103(6):377-379. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7997847/.

- Zacharenko E, Cataldo F, Wuyts E. Ensuring Sexual and Reproductive Safety in Times of COVID-19: IPPF Member Associations’ Advocacy Good Practices and Lessons Learned. London: International Planned Parenthood Federation Advocacy Advisory Group; 2020. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.ippf.org/resource/advocacy-good-practices-lessons-learned-ensuring-sexual-reproductive-safety-during-covid.

- Rab F, Razavi D, Kone M, et al. Implementing Community-Based Health Program in Conflict Settings: Documenting Experiences from the Central African Republic and South Sudan. BMC Health Services Research. 2023;23(1). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-023-09733-9.

- Ferguson L, Fried S, Matsaseng T, Ravindran S, Gruskin S. Human Rights and Legal Dimensions of Self Care Interventions for Sexual and Reproductive Health. BMJ. 2019;365:l1941. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l1941.

- Self-Care Trailblazer Group. Digital Self-Care: A Framework for Design, Implementation, and Evaluation. Washington, D.C.: Population Services International; 2020 September. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://media.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/31000510/Digital-Self-Care-Final.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43918/9789241596077_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- World Health Organization. Implementation of Self-Care Interventions for Health and Well-Being: Guidance for Health Systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/378232/9789240094888-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Burke HM, Packer C, Akuzike Zingani, et al. Testing a Counseling Message for Increasing Uptake of Self-Injectable Contraception in Southern Malawi: A Mixed-Methods, Clustered Randomized Controlled Study. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(10):e0275986-e0275986. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0275986.

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Social Norms: Promoting Community Support for Family Planning. Washington, D.C.: USAID; 2022 May. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://fphighimpactpractices.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/SocialNormsBrief_May2022_ENG_v9.pdf.

- Yousef H, Al-Sheyab N, Al Nsour M, et al. Perceptions Toward the Use of Digital Technology for Enhancing Family Planning Services: Focus Group Discussion with Beneficiaries and Key Informative Interview with Midwives. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(7):e25947. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34319250/

- Keesbury J, Morgan G, Owino B. Is Repeat Use of Emergency Contraception Common Among Pharmacy Clients? Evidence from Kenya. Contraception. 2011;83(4):346–351. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0010782410004737.

- Both R, Samuel F. Keeping Silent About Emergency Contraceptives in Addis Ababa: A Qualitative Study Among Young People, Service Providers, and Key Stakeholders. BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14(1). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-014-0134-5.

- Kalamar A, Bixiones C, Jaworski G, et al. Supporting Contraceptive Choice in Self-Care: Qualitative Exploration of Beliefs and Attitudes Towards Emergency Contraceptive Pills and On-Demand Use in Accra, Ghana and Lusaka, Zambia. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2022;29(3). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8942546/.

- Asali F, Mahfouz IA, Al-Kamil E, Alsayaideh B, Abbadi R, Zurgan Z. Impact of Coronavirus 19 Pandemic on Contraception in Jordan. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2022;42(6):2292–2296. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01443615.2022.2040969.

- Cover J, Namagembe A, Morozoff C, Tumusiime J, Nsangi D, Drake JK. Contraceptive Self-Injection Through Routine Service Delivery: Experiences of Ugandan Women in the Public Health System. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health. 2022;3. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9433546/.

- Burke HM, Chen M, Buluzi M, et al. Women’s Satisfaction, Use, Storage and Disposal of Subcutaneous Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (DMPA-SC) During a Randomized Trial. Contraception. 2018;98(5):418–422. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010782418301719.

- Cover J, Ba M, Drake JK, NDiaye MD. Continuation of Self-Injected Versus Provider-Administered Contraception in Senegal: A Nonrandomized, Prospective Cohort Study. Contraception. 2019;99(2):137–141. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6367564/.

- Cover J, Namagembe A, Tumusiime J, Nsangi D, Lim J, Nakiganda-Busiku D. Continuation of Injectable Contraception When Self-Injected vs. Administered by a Facility-Based Health Worker: A Nonrandomized, Prospective Cohort Study in Uganda. Contraception. 2018;98(5):383–388. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6197833/.

- Kennedy CE, Yeh PT, Gonsalves L, et al. Should Oral Contraceptive Pills Be Available without a Prescription? A Systematic Review of Over-the-Counter and Pharmacy Access Availability. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4(3):e001402. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/4/3/e001402.

- Logie CH, Berry I, Ferguson L, Malama K, Donkers H, Narasimhan M. Uptake and Provision of Self-Care Interventions for Sexual and Reproductive Health: Findings from a Global Values and Preferences Survey. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2022;29(3). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/26410397.2021.2009104.

- Burke HM, Mkandawire P, Phiri MM, et al. Documenting the Provision of Emergency Contraceptive Pills Through Youth-Serving Delivery Channels: Exploratory Mixed Methods Research on Malawi’s Emergency Contraception Strategy. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2024;12(5):e2400076. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/12/5/e2400076.

- World Health Organization. Self-Care Interventions for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: Country Cases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/379048/B09126-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Gonsalves L, Wyss K, Gichangi P, Hilber AM. Pharmacists as Youth-Friendly Service Providers: Documenting Condom and Emergency Contraception Dispensing in Kenya. International Journal of Public Health. 2020;65(4):487–496. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7275003/.

- Di Giorgio L, Mvundura M, Tumusiime J, Morozoff C, Cover J, Drake JK. Is Contraceptive Self-Injection Cost-Effective Compared to Contraceptive Injections from Facility-Based Health Workers? Evidence from Uganda. Contraception. 2018;98(5):396–404. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6197841/.

- Mvundura M, Di Giorgio L, Morozoff C, Cover J, Ndour M, Drake JK. Cost-Effectiveness of Self-Injected DMPA-SC Compared with Health-Worker-Injected DMPA-IM in Senegal. Contraception: X. 2019;1:100012. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336762111_Cost-effectiveness_of_self-injected_DMPA-SC_compared_with_health_worker-injected_DMPA-IM_in_Senegal.

- Remme M, Narasimhan M, Wilson D, et al. Self Care Interventions for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: Costs, Benefits, and Financing. BMJ. 2019;365:l1228. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l1228.

- Cover J, Namagembe A, Tumusiime J, Lim J, Cox CM. Ugandan Providers’ Views on the Acceptability of Contraceptive Self-Injection for Adolescents: A Qualitative Study. Reproductive Health. 2018;15(1). Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6169014/

- World Health Organization, United Nations University International Institute for Global Health. Meeting on Economic and Financing Considerations of Self-Care Interventions for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, 2–3 April 2019, New York: Summary Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Accessed July 27, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331195/WHO-SRH-20.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1.