Community Group Engagement: Changing Norms to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health

Background

This brief describes the evidence on and experience with community group engagement (CGE) interventions that aim to foster healthy sexual and reproductive health (SRH) behaviors. The distinguishing characteristic of CGE interventions from other social and behavior change (SBC) interventions is that they work with and through community groups to influence individual behaviors and/or social norms rather than shifting behavior by targeting individuals alone. Specifically, community support can shift individual behaviors, including contraceptive behaviors, either by changing norms or individual knowledge and attitudes (Storey et al., 2011).

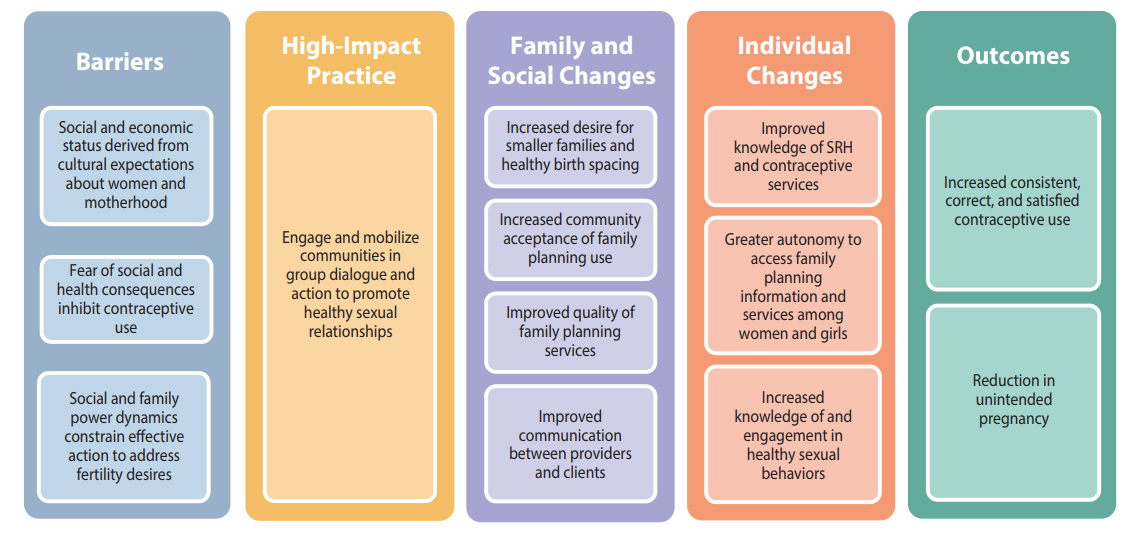

Individuals face many barriers to accessing and using contraceptives effectively, such as a fear of social and/or health consequences of using family planning. The barriers included in the illustrative theory of change for CGE shown in Figure 1 are based on a review of gender barriers to contraceptive use (McCleary-Sills et al., 2012) and reflect common issues addressed by CGE activities. Although the theory of change is set up in a linear, unidirectional format, it is likely that the mechanisms of action are multidirectional and more complex.

Community group engagement activities typically follow a defined process to identify and respond to perceived local drivers of and barriers to sexual and reproductive health. This approach seeks to maximize broad engagement and to move beyond conversations with decision makers and leaders to better understand sexual and reproductive health from the perspective of the community. Activities may include mapping exercises, social network approaches, exploratory games, dramas, case studies, prioritization exercises, and coalition-building, to name a few. Although activities may be facilitated by outsiders, such as NGO staff, public servants, or extension workers, they rely on active participation of local community groups and members to catalyze change.

Programs frequently implement CGE interventions as part of a package of interventions to influence the individual, family and/or peer group, and community simultaneously. Community group engagement should be linked with other SBC approaches (e.g., mass media, interpersonal communication, or counseling) and/or investments in service delivery improvement for greater impact.

Community group engagement interventions are one of several promising “high-impact practices in family planning” (HIPs) identified by a technical advisory group of international experts. A promising practice is one that has good evidence but more information is needed to fully document implementation experience and potential impact. The technical advisory group recommends that these interventions be promoted widely, provided they are implemented within the context of research and are carefully evaluated in terms of impact and process (HIPs, 2015). For more information about HIPs, see http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/overview.

Which challenges can community group engagement help countries address?

Women and girls derive social and economic status by conforming to cultural expectations about womanhood and motherhood. (McCleary-Sills et al., 2012). Gender norms that idealize sexual ignorance for girls and sexual prowess for boys are found globally (Kågesten et al., 2016; Marston and King, 2006). These norms underpin harmful social practices that contribute to poor health. For women and girls, these norms contribute to early marriage, social isolation, lack of power, limited mobility, and pressures to prove fertility by becoming pregnant early and often (Adams et al., 2013; Greene et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2014; McClearySills et al., 2012), and are reinforced through family and community. For example, child marriage is typically a decision made by parents, spouses, in-laws, and other gatekeepers (WHO, 2009; Daniel et al., 2008; Mathur et al., 2004; Shattuck et al., 2011). Providers support these practices by placing age or parity restrictions on contraceptive access or by requiring spousal consent (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2014, Tumlinson et al., 2015).

Studies show that CGE can improve both men’s and women’s SRH knowledge (Schuler et al., 2015). Limited knowledge and understanding of contraception and reproduction contribute to fear of the potential social and health consequences of using family planning. (McCleary-Sills et al., 2012). In many communities there is a general lack of understanding of the intersection between sex, reproduction, and contraception. Lacking such an understanding, women—and especially adolescent girls—may not effectively assess their pregnancy risk (McCleary-Sills et al., 2012, Sedgh et al., 2007).

Community group engagement can improve women’s decision-making power. Women’s ability to make and act on decisions is linked to contraceptive use (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2013; Kraft et al., 2014; Radice, 2014; Wang et al., 2013; WHO, 2010). Decision-making autonomy and ready access to or control over cash is critical to accessing contraceptive services (Miller et al., 2002; Keele et al., 2005). Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data from 31 countries found that women with greater involvement in household decisionmaking were 80% more likely to be using modern contraception than those with no decision-making power. Women’s involvement included decisions about their own health care, purchases of large household items or daily household needs, visits to their family or relatives, and daily meal preparation (Ahmed et al., 2010). Studies confirm that CGE can promote equitable gender norms and couple decision-making, and reduce acceptance of intimate partner violence (Schuler et al., 2015; Abramsky et al., 2014; Shattuck et al., 2011; Figueroa et al., 2016; Underwood et al., 2011).

Community group engagement likely influences change at the community, family, and individual levels by building capacity within the community. A study in Zambia demonstrated that CGE could improve social cohesion, collective ability to solve problems, conflict management, equitable and effective leadership, and participation/self-efficacy (Underwood et al., 2013). Individuals from communities that worked together to address health problems were over twice as likely to be currently using a modern contraceptive method than individuals from communities that did not work together to address health problems.

What is the impact?

Community group engagement is associated with higher levels of contraceptive use. In family planning programming, CGE is often used in combination with other SBC strategies and service delivery improvements. Studies using multivariate analysis of this combined approach have been conducted in Benin, Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal. Mulitvariate analysis allows researchers to assess the relationship between exposure to CGE and outcome measures, controlling for exposure to other intervention components. All four of these studies reported an increase in modern contraceptive use or a decline in fertility rates after two to three years of program implementation (Speizer and Lance, 2016; Debpuur et al., 2002; Population Council, 2012; IRH, 2016). The impact of implementing the comprehensive programs varied from an increase of 4 to 10 percentage points in modern contraceptive use in the intervention communities (Speizer and Lance, 2016; Debpuur et al., 2002; IRH, 2016). Multivariate analyses found that in all four countries CGE contributed significantly to the observed results (Speizer and Lance, 2016; Debpuur et al., 2002; IRH, 2016).

Intervention designs varied substantially between the programs. Programs in Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal emphasized activities working with religious or community leaders as well as the community at large (e.g., drama with group discussion), and they incorporated specific messages and activities. All programs, except the program in Ghana, included investments in mass media as well as other SBC strategies, such as print material. In addition, all programs, except the program in Benin, included significant investments to improve service delivery (Speizer and Lance, 2016; Debpuur et al., 2002; Ashburn et al., 2016).

Studies of CGE have been conducted in varied contexts among a wide range of population groups. For example, participatory theater, songs, and large mixed-group dialogue were used to explore barriers to accessing family planning in crisis settings in Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Mali, and Pakistan. Programs across these five countries supported 52,616 new modern contraceptive users over two and a half years (Curry et al., 2015). In Kenya, 150 trained community-based facilitators held ongoing community dialogues with men and women about gender, sexuality, and family planning over three and a half years. Women who participated in these dialogues were nearly 80% more likely to be using modern contraceptives at endline compared with women who did not participate in dialogues (Wegs et al., 2016). CGE is also a common approach for engaging men. In Malawi nearly 80% of men participating in a CGE program reported modern contraceptive use (Shattuck et al., 2011). Although studies of CGE in El Salvador and Guatemala demonstrated increased contraceptive use in comparison with the control groups, the differences were not statistically significant (Lundgren et al., 2005; Schuler et al., 2015).

Community group engagement may be a critical component of comprehensive adolescent SRH programming. Community group engagement can facilitate dialogue with influential individuals to identify and clarify values around adolescent marriage and childbearing and to address norms, myths, and misconceptions about adolescent sexuality (Dick and Chandra-Mouli, 2006; Daniel et al., 2008; Daniel and Nanda, 2012; Denno et al., 2015).

Eight studies of adolescent programs that included CGE were identified—three in India, two in Nepal, and one each in Burkina Faso, Bangladesh, and Uganda (Save the Children, 2009; Kanesathasan et al., 2008; Mathur et al., 2004; ACQUIRE, 2008; Thiombiano et al., 2006; IRH, 2016; Santhya et al., 2008; Daniel and Nanda, 2012). None of these studies included analysis to assess the unique contribution of CGE. Four of the studies measured program effect on early marriage, with all four demonstrating a positive impact (Save the Children, 2009; Kanesathasan et al., 2008; Mathur et al., 2004; ACQUIRE, 2008), which can contribute to better child and maternal outcomes. In Bangladesh, the mean age of marriage increased from 14.6 years to 15.4 years; in India, from 16 to 18; and in Nepal, from 14 to 16 (Save the Children, 2009; Kanesathasan et al., 2008; ACQUIRE, 2008). Seven studies reported on contraceptive use among married adolescent women. The results overall are inconclusive, which is consistent with the findings from a review conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2009). However, the three studies from India and the study in Uganda recorded large increases in modern contraceptive use—10 percentage points or higher (Daniel and Nanda, 2012; Santhya et al., 2008; IRH, 2016; Kanesathasan et al., 2008). Two other studies recorded minimal or no increase in contraceptive use (ACQUIRE, 2008; Thiombiano et al., 2006). One study in Nepal reported a decrease in contraceptive use; however, this decrease was greater in control sites suggesting the intervention may have dampened the rate of decrease (Mathur et al., 2004).

These eight adolescent programs were similar to the combined approach described above—all programs incorporated a variety of SBC approaches and service delivery improvements. In terms of target age groups, two programs in India and one in Nepal focused on married women younger than 20 years of age and their husbands (Daniel and Nanda, 2012; Santhya et al., 2008; ACQUIRE, 2008). The other programs included unmarried boys and girls between the ages of 10 to 24 in addition to married adolescents while the program in Burkina Faso did not report a target population group (Thiombiano et al., 2006).

Community group engagement has been implemented in other health areas at scale and cost-effectively. Large-scale implementation of CGE in family planning programs is not yet common place. Evidence for application of CGE in maternal and child health programs, however, demonstrates that this approach can lead to “cost-effective sustained transformation to improve critical health behaviors” (Farnsworth et al., 2014; Prost et al., 2013).

A multi-component intervention supported participants to reflect on social expectations related to being a boy or girl and how these norms influence sexual decision making and access to services. The CGE component involved a set of tools and a radio serial drama to promote dialogue and learning between groups of adolescents (ages 10–19) and members of their communities. The process was designed to engage community members and leaders to reflect on community norms, identify key issues, and develop and execute a plan of action. (IRH, 2016).

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

A group of experts convened to identify key components to successfully engaging communities in behavior change (Gumucio, 2001). The group emphasized focusing on outcomes beyond individual behavior to those related to social norms, policies, culture, and the supporting environment, recommended that:

- Communication for social change should be empowering, horizontal (versus top-down), and biased toward local content and ownership, and it should give a voice to previously unheard community members. Group dialogue, reflection, and tailored participatory activities can highlight the contribution of gender and other social norms to poor reproductive health outcomes. These approaches are also particularly useful for individuals with little power, such as adolescents and ethnic minorities. Community group engagement approaches may give marginalized groups a stronger collective voice and agency to affect health and social change for themselves, within their families, and across the larger community (Storey et al., 2011). Once local stakeholders and community members articulate and explore these dynamics, they are better equipped to develop and carry out contextually relevant strategies that enable social support for changing norms and improving SRH practices.

- Communities should be their own change agents. In addition to ensuring NGO staff understand how social norms shape their own behaviors, CGE interventions should support individual community members and the community as a whole, for example, by building capacity to lead group processes to promote informed decision-making and collective action (Cheetham, 2002; IAWG, 2007). Strengthening the capacity of local youth-led or youth-serving organizations is also recommended (Youth Health and Rights Coalition, 2011; IAWG, 2007). With increased capacity to identify and address problems that affect them and their community, these groups can tackle other issues as they arise.

- Emphasis should shift from persuasion and information transmission from outside technical experts to dialogue, debate, and negotiation on issues that resonate with community members. Community group engagement interventions should avoid predetermining solutions. Community group engagement facilitates a process through which communities identify root causes to problems and craft approaches to addressing these causes. Once the goal is clear, communities often benefit from flexibility to identify and implement their own localized responses. Such flexibility on the part of programs is likely to increase local ownership, capacity, and commitment to achieve and sustain the community’s desired results.

CGE programs should also:

- Reach young people, especially out-of-school youth. A 2009 review of adolescent programming for SRH from the World Health Organization concluded that out-of-school SRH education sessions allow for more open, participatory discussions compared with in-school education. Community members or established organizations that already serve young people, such as the Scout and Guide movements, can carry out the education and dialogue sessions in a sustainable, culturally sensitive way. The review recommends combining these educational sessions with community mobilization activities.

- Build on existing platforms whenever possible. Community group engagement interventions should assess the extent to which existing community platforms and groups include active participation of marginalized and/or affected populations. Using existing social infrastructure—both formal and informal— encourages sustainability and improves the possibility of effective replication and scale-up. Forming new groups, on the other hand, is resource-intensive and requires more ongoing efforts to sustain. Programs should bear in mind, however, that the most vulnerable populations such as adolescents and ethnic minorities may not feel comfortable participating within existing groups. In this case, these vulnerable groups may need support to express themselves and claim their rights to participation. When new community platforms are required, programs should add time in work plans—typically an additional six months to one year—for community entry and organizing.

- Layer and connect SBC approaches. Experts believe CGE works best when implementers create linkages and feedback mechanisms between multiple SBC approaches (for example, interpersonal counseling, group dialogue, and radio programming with harmonized themes) working to achieve the same aim. SBC health strategies that work at multiple levels and that use multiple channels likely have greater coverage and increase impact (Arora et al., 2012). As with all multifaceted and complex approaches, loss of effectiveness and efficiency during scale-up should be factored into planning (Maclean, 2006). Interventions should be designed with a vision of how to plan and support expanded implementation of proven components.

- Define monitoring and quality assurance mechanisms. As with other program approaches, implementation monitoring is necessary to ensure effective programming. Strategies such as low-dose (1 hour or less), high-frequency (once a month) implementation and follow-up sessions for group facilitators to share experiences and solve problems are useful to ensure high-quality programming. Observation checklists (on paper or mobile devices) for supportive supervision of group facilitators are also useful.

- Ensure political and resource commitment to CGE approaches. Community group engagement approaches often take ministries of health out of their comfort zone, which may lead them to deprioritize this intervention during scale-up, especially in the context of staff and resource shortages. For example, the long-term evaluation of the Navrongo project in Ghana showed that effective expansion of the CGE intervention was not sustained during scale-up, and thus the project did not sustain reductions in pregnancies when operating at scale (Phillips et al., 2012). High-quality data, as well as human interest stories from a diverse set of stakeholders who have been engaged from the beginning, can help build commitment. Other lessons on how to build this commitment may be found in efforts to secure buyin and stakeholder engagement for scaling up capacity-building interventions for youth, adults, and organizations (Diop et al., 2004; Daniel et al., [2013]; Mathur et al., 2004).

- Do CGE interventions influence key family planning outcomes among specific adolescent population groups, such as very young, married, or unmarried adolescents?

- How is CGE implemented at scale and what are the associated costs?

- What level/dose and coverage of CGE are sufficient to achieve sustained change in social norms and family planning behaviors?

Communication for Social Change: An Integrated Model for Measuring the Process and Its Outcomes provides a practical resource for community organizations, communication professionals, and social change activists working in development projects to assess the progress and the effects of their programs. Available from: http://www.communicationforsocialchange.org/pdf/socialchange.pdf

How to Mobilize Communities for Health and Social Change provides step-by-step guidance on how to use CGE to influence positive health behaviors. Available from: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadu080.pdf

For more information about High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs), please contact the HIP team.

References

Abramsky T, Devries K , Kiss L, Nakuti J, Kyegombe N, Starmann E, et al. Findings from the SASA! Study: a cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of a community mobilization intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV risk in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Med. 2014;12:122. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0122-5

ACQUIRE Project. Mobilizing married youth in Nepal to improve reproductive health: the Reproductive Health for Married Adolescent Couples Project, Nepal, 2005–2007. New York: EngenderHealth/The ACQUIRE Project; 2008. Available from: http://www.acquireproject.org/archive/files/11.0_research_studies/er_study_12.pdf

Adams MK, Salazar E, Lundgren R. Tell them you are planning for the future: gender norms and family planning among adolescents in northern Uganda. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123 Suppl 1:e7-e10. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.07.004

Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One. 2010;5(6): e11190. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011190

Ashburn K, Igras S, Diakite M. Effects of a social network diffusion intervention on key family planning indicators, unmet need and use of modern contraception household survey report on the effectiveness of the intervention. Presented at: Population Association of America Annual Meeting; 2016 Mar 31 – Apr 2; Washington, DC. Available from: https://paa.confex.com/paa/2016/mediafile/ExtendedAbstract/Paper6743/TJ_PAA_2016_abstract_22%20SEPT2015.pdf

Chandra-Mouli V, Greifinger R, Nwosu A, Hainsworth G, Sundaram L, Hadi S, et al. Invest in adolescents and young people: it pays. Reprod Health. 2013;10:51. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-10-51

Chandra-Mouli V, McCarraher DR, Phillips SJ, Williamson NE, Hainsworth G. Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income countries: needs, barriers, and access. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-11-1

Cheetham N. Community participation: what is it? Transitions. 2002;14(3):3. Available from: http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/publications/683-community

Curry DW, Rattan J, Nzau JJ, Giri K. Delivering high-quality family planning services in crisis-affected settings I: program implementation. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(1):14-24. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00164

Daniel E, Hainsworth G, Kitzantides I, Simon C, Subramanian L. PRACHAR: advancing young people’s sexual and reproductive health and rights in India. Watertown (MA): Pathfinder International; [2013]. Available from: http://www.pathfinder.org/publications-tools/pdfs/PRACHAR_Advancing_Young_Peoples_Sexual_and_Reproductive_Health_and_Rights_in_India.pdf

Daniel EE, Masilamani R, Rahman M. The effect of community-based reproductive health communication interventions on contraceptive use among young married couples in Bihar, India. Int Family Plann Perspect. 2008;34(4):189-197. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1363/ifpp.34.189.08

Daniel EE, Nanda R. The effect of reproductive health communication interventions on age at marriage and first birth in rural Bihar, India: a retrospective study. Watertown (MA): Pathfinder International; 2012. Available from: https://www.pathfinder.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/The-Effect-of-Reproductive-health-Communication-Interventions-on-Age-at-Marriage-and-First-Birth-in-Rural-Bihar-India.pdf

Debpuur C, Phillips JF, Jackson EF, Nazzar A, Ngom P, Binka FN. The impact of the Navrongo Project on contraceptive knowledge and use, reproductive preferences, and fertility. Stud Family Plann. 2002;33(2):141–164. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/councilarticles/sfp/SFP332Debpurr.pdf

Denno DM, Hoopes AJ, Chandra-Mouli V. Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. J Adolesc Health 2015;56(1 Suppl):S22-S41. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.012

Diop NJ, Faye MM, Moreau A, Cabral J, Benga H, Cissé F, et al. The TOSTAN program: evaluation of a community based education program in Senegal. New York: Population Council, GTZ, and TOSTAN; 2004. Available from: https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/TOSTAN%20program_Evaluation%20of%20CommBased%20Edu%20Pgm_Senegal.pdf

Figueroa ME, Poppe P, Carrasco M, Pinho MD, Massingue F, Tanque M, et al. Effectiveness of community dialogue in changing gender and sexual norms for HIV prevention: evaluation of the Tchova Tchova Program in Mozambique. J Health Commun. 2016;21(5):554-563. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1114050

Farnsworth SK, Böse K, Fajobi O, Souza PP, Peniston A, Davidson LL, et al. Community engagement to enhance child survival and early development in low- and middle-income countries: an evidence review. J Health Commun. 2014;19 Suppl 1:67-88. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.941519

Greene ME, Gay J, Morgan G, Benevides R, Fikree F. Literature review: reaching young first-time parents for the healthy spacing of second and subsequent pregnancies. Washington (DC): Pathfinder International, Evidence to Action Project; 2014. Available from: http://www.e2aproject.org/publications-tools/pdfs/reaching-first-time-parents-for-pregnancy-spacing.pdf

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). High impact practices in family planning list. Washington (DC): U.S. Agency for International Development; 2015. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/high-impact-practices-in-family-planning-list

Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH), Georgetown University. GREAT project endline report. Washington (DC): IRH; 2016. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00KXRW.pdf

Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH), Georgetown University. GREAT Project Results Brief. Washington (DC): IRH, 2016. Available from: http://irh.org/resource-library/brief-great-project-results/

Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH), Georgetown University. Tekponon Jikuagou Brief: Project Results. Washington (DC): IRH, 2016. Available from: http://irh.org/resource-library/tekponon-jikuagou-brief-project-results/

Inter-Agency Working Group (IAWG) on the Role of Community Involvement in ASRH. Community pathways to improved adolescent sexual and reproductive health: a conceptual framework and suggested outcome indicators. Washington (DC): IAWG; 2007. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/asrh_pathways.pdf

Kågesten A, Gibbs S, Blum RW, Moreau C, Chandra-Mouli V, et al. Understanding factors that shape gender attitudes in early adolescence globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157805. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157805

Kanesathasan A, Cardinal LJ, Pearson E, Das Gupta S, Mukherjee S, Malhotra A. Catalyzing change: improving youth sexual and reproductive health through DISHA, an integrated program in India. Washington (DC): International Center for Research on Women, 2008. Available from: http://www.icrw.org/files/publications/Catalyzing-Change-Improving-Youth-Sexual-and-Reproductive-Health-Through-disha-an-Integrated-Program-in-India-DISHA-Report.pdf

Keele J, Forste R, Flake D. Hearing native voices: contraceptive use in Matemwe Village, East Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9(1):32-41. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3583158

Kraft JM, Wilkins KG, Morales GJ, Widyono M, Middlestadt SE. An evidence review of gender-integrated interventions in reproductive and maternal-child health. J Health Commun. 2014;19 Suppl 1:122-141. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.918216

Lundgren RI, Gribble JN, Greene ME, Emrick GE, de Monroy M. Cultivating men’s interest in family planning in rural El Salvador. Stud Family Plann. 2005;36(3):173-188. Available from: http://irh.org/resource-library/cultivating-mens-interest-in-family-planning-in-rural-el-salvado/

Maclean A. Community involvement in youth reproductive health and HIV prevention: a review and analysis of the literature research. Research Triangle Park (NC): FHI 360; 2006. Available from: https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/Community%20Involvement%20in%20Youth%20Reproductive%20Health_1.pdf

Mathur S, Mehta M, Malhotra A. Youth reproductive health in Nepal: is participation the answer? Washington (DC): International Center for Research on Women; 2004. Available from: http://www.icrw.org/files/publications/Youth-Reproductive-Health-in-Nepal-Is-Participation-the-Answer.pdf

Marston C, King E. Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;368(9547):1581-1586. Available from: http://nclc203seminarf.pbworks.com/f/Cicely+Marston,+Eleanor+King+2006.pdf

McCleary-Sills J, McGonagle A, Malhotra A. Women’s demand for reproductive control: understanding and addressing gender barriers. Washington (DC): International Center for Research on Women; 2012. Available from: https://www.icrw.org/files/publications/Womens-demand-for-reproductive-control.pdf

Miller S, Tejada A, Murgueytio P, Diaz J, Dabash R, Putney P, et al. Strategic assessment of reproductive health in the Dominican Republic. New York: Population Council; 2002. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnacp757.pdf

Phillips JF, Jackson EF, Bawah AA, MacLeod B, Adongo P, Baynes C, et al. The long-term fertility impact of the Navrongo Project in northern Ghana. Stud Fam Plann. 2012;43(3):175–190. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23885004

Population Council. Family Advancement for Life and Health (FALAH): end of project report. New York: Population Council; 2012.

Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, et al. Women’s groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9879):1736-1746. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60685-6

Radice A. Influencing the sexual and reproductive health of urban youth through social and behavior change communication: a literature review. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Health Communication Capacity Collaborative; 2014. Available from: http://healthcommcapacity.org/hc3resources/influencing-sexual-reproductive-health-urban-youth-social-behavior-change-communication/

Santhya KG, Haberland N, Das A, Lakhani A, Ram F, Sinha RK, et al. Empowering married young women and improving their sexual and reproductive health: effects of the First-time Parents Project. New Delhi: Population Council; 2008. Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/ForcedMarriage/NGO/PopulationCouncil23.pdf

Save the Children. Endline evaluation of adolescent reproductive and sexual health program in Nasirnagar 2008. Dhaka (Bangladesh): Save the Children USA, Bangladesh Country Office; 2009. Available from: http://resourcecentre.savethechildren.se/sites/default/files/documents/endline_survey_report_kaishar_ek_pdf.pdf

Sedgh G, Hussain R, Bankole A, Singh S. Women with an unmet need for contraception in developing countries and their reasons for not using a method. Occasional Report No. 37. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2007. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pubs/2007/07/09/or37.pdf

Schuler SR, Nanda G, Ramírez LF, Chen M. Interactive workshops to promote gender equity and family planning in rural communities of Guatemala: results of a community randomized study. J Biosoc Sci. 2015;47(5):667-686.

Shattuck D, Kerner B, Gilles K, Hartmann M, Ng’ombe T, Guest G. Encouraging contraceptive uptake by motivating men to communicate about family planning: the Malawi Male Motivator project. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6): 1089-1095. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3093271/

Singh S, Darroch JE, Ashford LS. Adding it up: the costs and benefits of sexual and reproductive health. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2014. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/addingitup2014.pdf

Speizer IS, Lance PM. The Measurement, Learning and Evaluation Project: background, design, results and lessons from a large, multi-country longitudinal impact evaluation. Presented at: U.S. Agency for International Development; 2016 Aug 29; Washington, DC. Available from: https://www.urbanreproductivehealth.org/sites/mle/files/usaiddraft_final_pml3_002_1.pdf

Storey D, Lee K, Blake C, Lee P, Lee H, Depasquale N. Social and behavior change interventions landscaping study: a global review. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for Communication Programs; 2011. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271706961_Social_and_Behavior_Change_Interventions_Landscaping_Study_A_Global_Review

Thiombiano R, Ky S, Cheetham N. Les Juenes se prennent en charge: synthese du programme de participation communitaire pour la sante reproductive et sexuelle des juenes au Burkina Faso. Washington (DC): Advocates for Youth; 2006. Available from: http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/storage/advfy/documents/burkina.pdf

Tumlinson K, Okigbo CC, Speizer IS. Provider barriers to family planning access in urban Kenya. Contraception. 2015;92(2):143-151. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4506861/

Underwood C, Boulay M, Snetra-Plenwman G, Macwan’gi M, Vijayaraghavan J, Namfukwe M, et al. Community capacity as means to improved health practices and an end in itself: evidence from a multi-stage study. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2012-2013;33(2):105-127.

Underwood C, Brown J, Sherard D, Tushabe B, Abdur-Rahman A. Reconstructing gender norms through ritual communication: a study of African Transformation. J Commun. 2011;61:197–218

Wang W, Alva S, Winter R, Burgert C. Contextual influences of modern contraceptive use among rural women in Rwanda and Nepal. DHS Analytical Studies 41. Calverton (MD): ICF International; 2013. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnaec676.pdf

Wegs C, Creanga AA, Galavotti C, Wamalwa E. Community dialogue to shift social norms and enable family planning: an evaluation of the Family Planning Results Initiative in Kenya. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153907. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153907

World Health Organization (WHO). Generating demand and community support for sexual and reproductive health services for young people: a review of the literature and programmes. Geneva: WHO; 2009. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44178/1/9789241598484_eng.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO). Social determinants of sexual and reproductive health: informing future research and programme implementation. Geneva: WHO; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/social_science/9789241599528/en/

Youth Health and Rights Coalition. Promoting the sexual and reproductive rights and health of adolescents and youth. Washington (DC): Youth Health and Rights Coalition; 2011. Available from: http://www.pathfinder.org/publications-tools/pdfs/Promoting-the-sexual-and-reproductive-rights-and-health-of-Adolescents-and-Youth.pdf

Suggested Citation

High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Community engagement: changing norms to improve sexual and reproductive health. Washington, DC: USAID; 2016 Oct. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/community-group-engagement.

Acknowledgements

This document was written by Kate Plourde, Joy Cunningham, Meagan Brown, Kerry Aradhya, Shegufta Sikder, Joan Kraft, Shawn Malarcher, Hope Hempstone, and Angela Brasington. Critical review and helpful comments were provided by Afeefa Abdur-Rahman, Peggy D’Adamo, Jennifer Arney, Michal Avni, Doortje Braeke, Wendy Castro, Paata Chikvaidze, Tamar Chitashvili, Arzum Ciloglu, Chelsea Cooper, Kristen Devlin, Ellen Eiseman, Debora Freitas, Jill Gay, Jay Gribble, Gwyn Hainsworth, Karen Hardee, Laura Hurley, Cate Lane, Rebecka Lundgren, Erin Mielke, Danielle Murphy, Maggwa Ndugga, Maureen Norton, Gael O’Sullivan, Shannon Pryor, Suzy Sacher, Amy Sedig, Ritu Shroff, Reena Shukla, Gail Snetro, Linda Sussman, Feven Tassew, Nandita Thatte, Caitlin Thistle, Caroll Vasquez, and Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli.

This brief is endorsed by: Abt Associates, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, CARE, Chemonics International, EngenderHealth, FHI 360, FP2020, Georgetown University/Institute for Reproductive Health, International Planned Parenthood Federation, IntraHealth International, Jhpiego, John Snow, Inc., Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Management Sciences for Health, Marie Stopes International, Palladium, Pathfinder International, Population Council, Population Reference Bureau, Population Services International, Save the Children, United Nations Population Fund, United States Agency for International Development, and University Research Co., LLC.

The World Health Organization/Department of Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/.