Family Planning Mobile Outreach Services: Expanding Equitable Access to a Full Range of Modern Contraceptives

Background

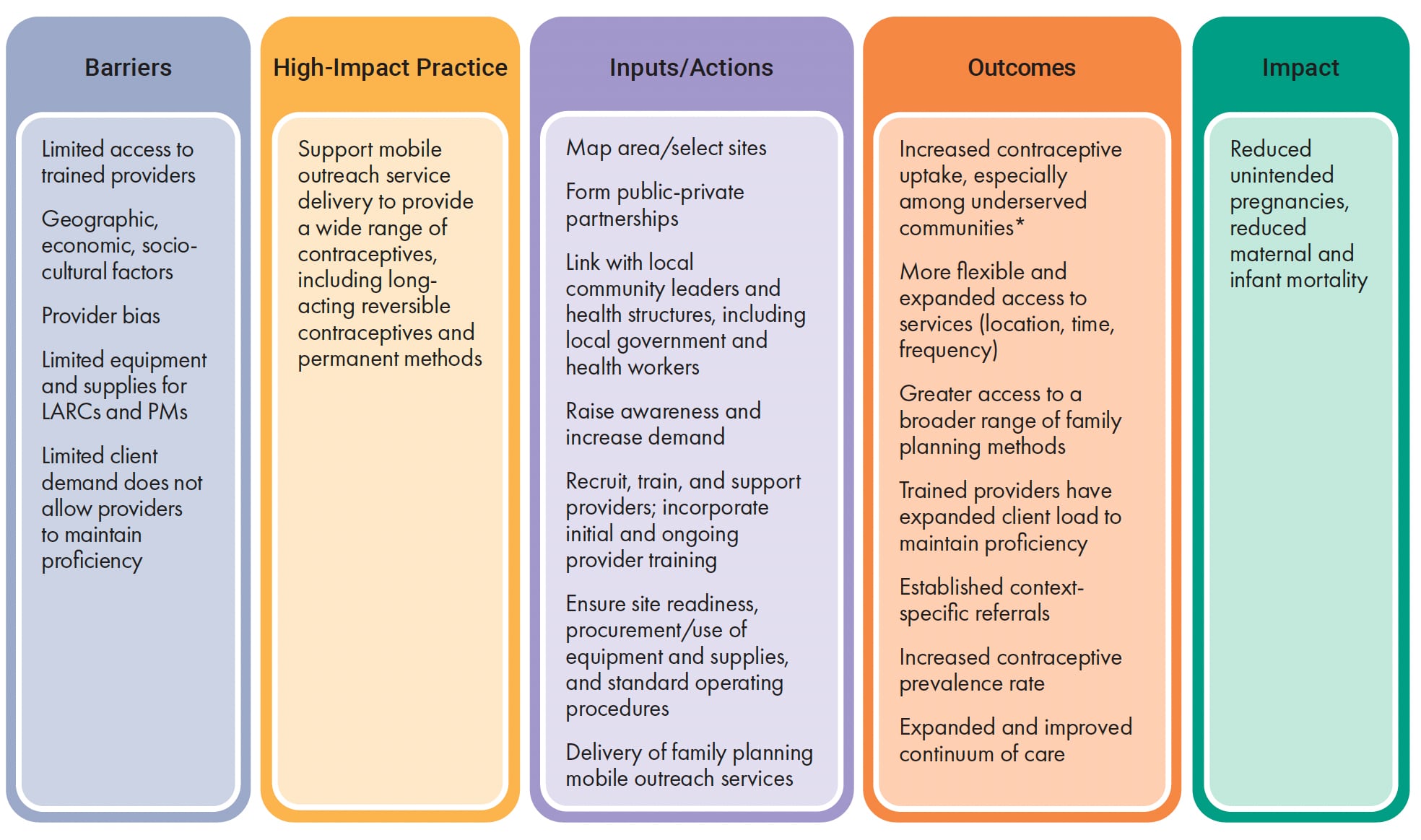

Family planning mobile outreach services enable the flexible and strategic use of resources. They also expand access to safe and voluntary family planning services, including trained health care providers, family planning commodities, supplies, equipment, and infrastructure at intervals that most effectively meet demand. Family planning mobile outreach can occur in permanent community structures, such as health facilities that do not routinely offer these methods and other permanent locations (schools, religious buildings, social/town halls), or in temporary facilities (tents, vehicles).1 Mobile services can be a practical cost-effective and long-term solution for health systems to deploy skilled health workers and improve access to health care. For some specialized services (for example, permanent methods), it may be effective to train fewer personnel and deploy them on mobile outreach teams.

Evidence highlights the efficacy of mobile outreach services to significantly enhance contraceptive use, particularly in areas of low contraceptive prevalence or high unmet need for family planning, and where geographic, economic, or social barriers, such as stigma and discrimination, limit access and service uptake. Family planning mobile outreach services improve access to all clients and have been widely used to help provide family planning services to a range of underserved populations, including those living in poverty or in peri-urban and rural settings; and displaced or marginalized populations, including adolescents and youth.2,3 In humanitarian settings (conflict areas and pandemic- or epidemic-exposed areas), mobile health clinics can serve as a flexible and adaptable means of providing essential family planning services to communities,4 offering an opportunity for new clients in addition to those who desire to continue care, through an expanded continuum of care model.

Mobile outreach is one of several proven High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs) identified by a technical advisory group of international experts. When scaled and institutionalized, HIPs can maximize investments in a comprehensive family planning strategy. For more information about HIPs, see www.fphighimpactpractices.org/.

Mobile outreach for family planning refers to a service delivery approach that brings trained providers, equipment, and supplies to locations to better reach populations with diverse access challenges or barriers. Trained providers expand method choice by offering counseling and access to a full range of contraceptive services, including long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), permanent methods (PMs), and short-acting methods. Services emphasize informed choice, voluntarism, and client contraceptive choice. Demand creation and awareness raising typically precede family planning mobile outreach.

Mobile outreach service delivery models

An array of mobile outreach service delivery models has been implemented globally with success and at large scale. The delivery models vary in who provides the services, location of service delivery, recipients of care, and the dynamics and shared responsibilities between stakeholder providers and the community. Mobile outreach services are often implemented through partnerships between the government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector (public-private partnerships) and act to fill service delivery gaps or strengthen the public health system by expanding the reach of trained providers, commodities, and services in accessible locations. The service model can vary based on availability of resources and local needs, with differences in staffing composition, supply source, types of services provided, and the location of the actual service provision.

Table 1 is shared to assure that communities and providers are broadly familiar with the ways mobile outreach can be arranged; the purpose of this table is to explain the different models so communities can choose which to implement depending on context and needs. Implementation can involve a mix of model types within a community or a combination of approaches to meet client needs.

Models for Mobile Outreach Service Delivery

| Classic Model | Split Model | Streamlined Model (dedicated provider) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What | Services Provided | Permanent methods; LARC insertions and removals; short-acting methods | LARC insertions and removals; short-acting methods; referrals for permanent methods (provision may be possible if a doctor is on the team) | LARC insertions and removals; short-acting methods; vasectomy and tubal ligations; or referrals for permanent methods |

| A strong system must be in place for adequate follow-up care, particularly for clients receiving LARCs/PMs Continuity of care should be ensured for any short-acting methods provided |

||||

| How | Strategy | Resource-intensive model that includes multiple providers. | Splits classic mobile outreach team to create sub-teams that can provide simultaneous mobile clinics in different communities. May rely more heavily on public sector providers to help staff the teams. Rotate between peri-urban and rural areas. | Lean service model that allows individual providers to bring technical expertise to local clinic settings. Providers may be attached to or employed by the facility, such as a district hospital, but are mobile to offer services at lower-level facilities. |

| Supplies and Transport | Travel in large vehicles allows teams to bring all necessary supplies and equipment, permitting services in a broader variety of settings. | Clinical host sites provide large equipment such as exam tables so providers can travel with minimal supplies via local transport, motorcycles, or other small vehicles. | ||

| Who | Staff Composition |

|

|

|

| *Defined as medical doctor, assistant medical clinical officer, nurse, or nurse midwife | ||||

| Where | Location | Rural or hard-to-reach areas; peri-urban and urban | Peri-urban and urban | |

| Site | Sites may vary between clinical and community facilities, formal and informal settings, and permanent and temporary sites, depending on national health guidelines around services to be provided. | |||

| Model Application Notes | Benefits |

|

|

|

| Special Considerations | With sufficient local referrals and local capacity at the host facility, complications are able to be well managed. | |||

| Data collection may vary across service sites and service delivery models. | ||||

| If staff are alone for some or all of a day, they may experience greater security risks. | ||||

|

||||

What challenges can family planning mobile outreach address?

Accessibility. Mobile outreach makes services more accessible to underserved populations.

Mobile outreach brings family planning services and supplies closer to where people live and work. This is particularly critical for populations in rural areas. Populations facing specific barriers where normal services for family planning get interrupted (as in natural disaster settings) can be better served through mobile outreach services.1,5,6,7

Confidentiality. Mobile outreach services can provide client-preferred privacy and confidentiality.

Mobile services can offer increased privacy for clients who prefer the confidentiality of a mobile clinic over a community health center. This can reduce stigma, especially as related to certain demographic characteristics such as age (adolescents), marital status, sexual orientation, and economic status.8

Cost. Mobile outreach services can be more cost effective than community health centers.

The building and staffing of permanent health centers can be prohibitively costly, particularly in rural and hard-to-reach communities. Mobile outreach services can provide a cost-effective alternative for meeting client needs with quality services and a ready supply of contraceptives. Mobile outreach provides both the human resources and supplies needed in often hard-to-reach areas, significantly increasing access, even within an existing budget.10,11 Mobile outreach can also prove to be cost saving for clients, particularly in decreasing the cost of travel and time away from work and school.12

Community engagement. Mobile outreach can increase community engagement, increasing family planning uptake.

Mobile outreach services are an opportunity for community involvement in the planning and implementation of family planning services. Services are geared to community needs. This can foster engagement and trust, increasing uptake of family planning, reducing misinformation, and improving awareness of services.13

Provider training. Mobile outreach can offer increased opportunities for training and mentorship.

Mobile services can provide the critical number of clients needed for the practice of counseling and clinical skills by providers in training. Mobile services offer opportunities for new staff, as well as existing staff as needed, to receive on-the-job training, coaching, and skills improvement in both long-acting and permanent contraceptive methods.6 Task sharing has permitted the training of mid-level health care providers so they can engage in clinical procedures otherwise performed by higher-level providers, thus expanding the number of providers as well as family planning procedures in rural and peri-urban areas.14

Through mobile outreach and public health strengthening in conflict-affected northern Uganda, the country was able to increase current use of any modern family planning method and current use of long-acting and permanent methods, while decreasing the proportion of women with unmet need for family planning.7

In Malawi, 274 integrated mobile outreach clinics had a special focus on young people ages 15-24 in 2020.9 In another study, data indicated that 18.5% of the project’s family planning mobile outreach clients across 15 countries in Africa and Asia in 2022 were under 20 (MSI, routinely collected multi-country data, 2022).

What is the impact?

Mobile outreach increases access to underserved populations experiencing limited access to clinical family planning services, including those living in rural and poor areas as well as conflict-affected settings.

Mobile outreach services can expand access to underserved and hard-to-reach populations and increase their uptake of family planning services; often, most women reached by mobile outreach are from rural areas and poor households and have no education.1,5 Data from one organization implementing mobile outreach globally indicated that 53% of the people they reached stated that they do not know of another option to get the contraception method of their choice.9 Mobile outreach services support the delivery of a full range of contraceptive methods and quality family planning services to populations with diverse access barriers. By delivering information, clinical services, contraceptives, and supplies closer to where clients (particularly adolescents) live and work, at reduced or no cost, mobile outreach mitigates access barriers to care for groups including the following:

- Populations facing geographic and economic barriers. Many people living in remote or rural areas, urban slums, and poverty do not have access to a range of family planning methods, especially long-acting or permanent methods.15 Family planning mobile outreach can make high-quality family planning services accessible for populations facing significant barriers. At the same time, it can expand method choice by bringing health services closer to the client.2,15,16,17

- Populations experiencing a humanitarian emergency. Mobile outreach can increase access to family planning services in humanitarian settings (conflict areas and pandemic- or epidemic-exposed areas), and in health and climate crises. In such settings women often have greater desire to delay pregnancy until a return to stability and have increased need for family planning services. These settings are frequently associated with greater risk of unplanned pregnancies due to sexual and gender-based violence, sexual exploitation, transactional sex, and early or forced marriage.4

- Adolescents and youth. Multiple individual, interpersonal, community, and health system factors hinder youth access to a full range of family planning services and contraceptive methods.18,19 Provider bias against provision of various contraceptive methods to young people based on age, marital status, and other factors is common.20 In many contexts, family planning mobile outreach has demonstrated success by making services more accessible to adolescents and youth by increasing privacy, lowering transportation costs, and reducing travel times.8,11

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, and Uganda, LARCs and PMs were more likely to be selected by clients than by clients at permanent services centers.5

In conflict-affected northern Uganda, there was an increase in use of LARCs and PMs from 1.2% to 9.8%.7

In Togo, where family planning mobile outreach services were implemented to provide a broader range of options in underserved rural areas, 58% of all LARCs were provided through mobile outreach activities.22

Family planning mobile outreach can increase method choice, improving access to often hard-to-access LARCs and PMs.

Access to a full range of contraceptive services, especially LARCs and PMs, is limited in many communities. Mobile outreach services can supplement widely available methods and increase access to a wider range of contraceptive options to communities where they are typically unavailable. Mobile outreach services have been shown to play an important role in expanding access to LARCs and PMs in multiple contexts.21 A family planning mobile outreach program noted that “Mobile outreach services that enable rural clients to access high-quality family planning counseling and a broad range of voluntary family planning methods are feasible and can result in increased family planning users even in fragile and hard-to-reach settings with very low mCPR [modern contraceptive prevalence rate].”32 Evidence from multiple studies suggests that mobile outreach services are effective at increasing contraceptive use.2,15,16,17

Family planning mobile outreach can expand family planning access and method choice to new users.

Though providing an opportunity to reach and resupply or follow up with existing users, a majority of clients accessing contraception through mobile outreach are new users or adopters of a method or had not previously used a method.2,23 In a project providing targeted support for family planning mobile outreach across multiple countries, two-thirds of clients in Burkina Faso were not using a family planning method when they presented for their service. In Senegal 69% of women in Kaffrine and 45% of women in Diourbel were completely new to use of modern family planning ((MSI, routinely collected multi-country data, 2022). In one study in Togo, the majority (65%) of clients using mobile outreach services for family planning were first-time users.21 In a cross-country expansion initiative, 46% of LARC users at mobile clinics were adopters who had not used a modern family planning method in the previous three months.2 Mobile outreach can support family planning when integrated with other services such as child immunization.24

Mobile outreach services can increase awareness of family planning, reduce misconceptions about family planning services and methods, and encourage and support contraceptive continuation particularly among those who are more likely to discontinue use.

Mobile outreach services provide information about the full range of family planning methods, address client concerns, and offer appropriate counseling about all methods, including LARCs and PMs.25 Demand generation and awareness raising typically precede mobile outreach and can enhance use of modern contraception.13 Peer engagement has been used to complement mobile outreach efforts in some contexts by increasing uptake of family planning services in target populations.3 When clients are treated with care and respect and their needs are met, they are more satisfied, more likely to return, and more likely to refer others. Research shows that positive client–provider interactions lead to greater client knowledge, satisfaction, better adherence to treatment, and improved health outcomes.33 Programmatic experience has shown that mobile outreach supports contraceptive continuation and the continuum of care, particularly among youth, who are more likely to discontinue; this is dependent on coordinating regular frequency of mobile visits.

Mobile outreach services promote provider excellence, reduce provider bias, and improve access to supplies.

Regular visits by family planning mobile outreach providers to under-resourced health facilities offer opportunities for providers to get on-the-job training to build and reinforce family planning clinical care, counseling, client flow management, administrative skills, and monitoring and evaluation. Mobile outreach can provide training to reduce provider bias for specific methods and toward specific demographics.26 In one study, most providers were receptive to a self-injection method for adult women, but less than half were supportive of adolescent self-injection. Their reservations focused on whether young women, women who are unmarried, and women without children should use the injectable method.20 Mobile outreach services can help to ensure a reliable supply of contraceptive commodities, medical supplies, and equipment. Follow-up outreach days provide observation of counseling, insertions, and removals by host providers, along with quality assurance.27

Mobile contraceptive services are essential for enhancing access to care and can ensure that all individuals have the opportunity to make informed choices about their reproductive health. Mobile outreach not only addresses critical gaps in service delivery but also fosters sustainability and accountability in health care provision. Shifting responsibility to the government, though currently uncommon, empowers local health systems, promotes equity, and ultimately contributes to improved health outcomes. Investing in mobile outreach is not just a public health imperative; it is a commitment to safeguarding the rights and well-being of every citizen.

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

Map the geographic area and select family planning mobile outreach model, sites, and frequency.

Map the location of focus communities within a catchment area to identify optimal sites for mobile outreach, including schools and rural areas. Review mobile outreach models and select/design the model(s) best suited to the local context (see Table 1).

Form public-private partnerships and ensure coordination.

Mobile outreach service arrangements often allow ministries of health, NGOs, and the private sector to collaborate through public-private partnerships to expand reach and meet national health goals. Coordination with local governments in advance of mobile outreach visits facilitates logistics and continuity of care.

Link with community health workers and local health clinics.

Within the public sector, connecting mobile outreach programs with community health workers28 and local clinics can enhance family planning counseling, referrals, and community mobilization. Community health workers typically live in and are selected by the communities in which they operate. Connecting mobile outreach services with local resources offers opportunities for direct referrals. When participating in any intervention or programming involving sexual and reproductive health and people with disabilities, a first step is to partner with existing local organizations that work with disabled people.29

Coordinate with community leaders to raise awareness.

Routine communication, advocacy, and coordination with community leaders are key to enlist and maintain their support, which is critical to the success of mobile outreach service delivery. Community leaders play important roles in understanding the community context, including overcoming key barriers for clients with unmet need for family planning and establishing trust in providers.

Recruit, train, and support providers to provide quality, respectful care, including counseling services and referral for additional care.

Mobile outreach providers can be recruited and trained in family planning by the government, NGOs, or the private sector. Providers may be full-time employees, part-time employees, or ad hoc teams put together for each episode of mobile outreach. Task sharing can be implemented to increase provider availability.30 Regularly reviewing and rotating staff work plans and schedules can mitigate staff turnover. Setting travel dates in advance can make the arrival of the mobile team or provider predictable for both clients and providers.

Ensure site safety, privacy, confidentiality, comfort, and cleanliness.

Mobile outreach sites must be safe, comfortable, and clean, and they must ensure privacy during counseling, procedures, and recovery. It is critical to maintain infection prevention and control in accordance with international guidelines and standards.

Establish procedures to guide client access to follow-up care.

Mobile outreach sites should have detailed standard operating procedures consistent with national guidelines to refer clients for follow-up care. Where possible, provide written follow-up information to clients.

Establish procedures for data collection, recording, and inputting data into context-appropriate repositories.

Mobile outreach sites should have in place procedures and detailed standard operating procedures for best practices in data collection and linking client data to context-specific data repositories for follow-up. Record data within, or link data to, government registries such as health facility registers or electronic medical records.

Assure voluntarism and informed choice.

An individual’s decision to use a specific method of family planning, or whether to use any method at all, is voluntary if it is based on the exercise of free choice and is not obtained by any special inducements or coercion. “Informed choice” means that the potential family planning client has access to information on family planning choices and to the counseling, services, and supplies needed for individuals to choose to obtain or decline services; to seek, obtain, and follow up on a referral; or simply to consider the matter further.31

Implementation Measurement and Indicators

All indicators collected should be disaggregated by age group, sex, and family planning method, as possible. Consider disaggregation by socio-economic factors based on context and to evaluate whether target populations are being reached. Be sure to set a time frame (annually, quarterly) for collection.

- Clients provided with family planning services through mobile outreach. (a) Available method mix during outreach offered by the team/provider and at the host facility, and percent/number distributed or provided; (b) Number of family planning method removals; availability of method removals; continuation rate.

- Quality of services provided. (a) Client satisfaction measures such as wait and travel times measured by satisfaction surveys; (b) Clinical indicators such as complication rates from sterilizations (as implemented).

- Number and type of mobile outreach services. (a) Number of family planning mobile outreaches conducted; (b) Number of communities in the target district where family planning is provided to young people within a context-appropriate time period; (c) Number of services provided in mobile outreach.

TCI Global Toolkit: Service Delivery Mobile Outreach Services provides a step-by-step guide to implementing mobile outreach services.

Support for International Family Planning Organizations Final Performance Monitoring Report provides an overview of SIFPO-MSI and its key results.

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs) Data for Impact provides data for impact and reports on the results of a qualitative assessment of quality and scale of implementation for three service delivery HIPs, including mobile outreach, in Bangladesh and Tanzania.

Approaches to Mobile Outreach Services for Family Planning: A Descriptive Inquiry in Malawi, Nepal, and Tanzania. The RESPOND Project, August 2014.

Priority Research Questions

- What are the best practices for ensuring cost-effective and sustainable service delivery within family planning mobile outreach?

- What are the best practices in quality assurance for family planning mobile outreach?

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Family Planning Mobile Outreach Services: Expanding Equitable Access to a Full Range of Modern Contraceptives. Washington, DC: HIP Partnership; August 2025. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/mobile-outreach-services/.

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by: Dina Abbas (MSI), Levent Cagatay (EngenderHealth), Comfort Chizinga (Palladium), Erin Milke (USAID), Collins Otieno (Amref Health Africa), Heidi Quinn (UNFPA), Sahil Tandon (David and Lucile Packard Foundation), Eleanor Unsworth (WINGS Guatemala), and HIPs writer Linda Cahaelen (Independent). It was updated from a previous version, published in 2014, available here https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/previous-brief-versions/

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Maria Carrasco (USAID), Emeka Nwachukwu (USAID), Karen Hardee (What Works Associates), and others who commented via the HIPs website.

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception.

References

- The Challenge Initiative. TCI Global Toolkit: Service Delivery Mobile Outreach Services. Baltimore: The Challenge Initiative. N.d. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://tciurbanhealth.org/courses/core-package/lessons/mobile-outreach-services/.

- Ngo TD, Nuccio O, Pereira SK, Footman K, Reiss K. Evaluating a LARC Expansion Program in 14 Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Service Delivery Model for Meeting FP2020 Goals. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2016 May;21(9):1734-1743. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5569118/.

- Malkin M, Mickler AK, Ajibade TO, et al. Adapting High Impact Practices in Family Planning During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences From Kenya, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2022 August;10(4). Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9426984/.

- Gee S, Schulte-Hillen C, Noznesky L. Contraception and Family Planning in Refugee Settings, Part 1. Geneva: UNHCR; 2019 December. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/contraception-and-family-planning-refugee-settings-part-1.

- Jarvis L, Wickstrom J, Shannon C. Client Perceptions of Quality and Choice at Static, Mobile Outreach, and Special Family Planning Day Services in 3 African Countries. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2018 October 4;6(3):439-455. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/6/3/439.

- Wickstrom J, Yanulis J, Van Lith L, Jones B. Approaches to Mobile Outreach Services for Family Planning: A Descriptive Inquiry in Malawi, Nepal, and Tanzania. New York: The RESPOND Project/EngenderHealth; The RESPOND Project Study Series: Contributions to Global Knowledge—Report No. 13. 2013 August. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20170809091133/https://www.respond-project.org/pages/files/6_pubs/research-reports/Study13-Mobile-Services-LAPM-September2013-FINAL.pdf.

- Casey SE, McNab SE, Tanton C, Odong J, Testa AC, Lee-Jones L. Availability of Long-Acting and Permanent Family-Planning Methods Leads to Increase in Use in Conflict-Affected Northern Uganda: Evidence from Cross-sectional Baseline and Endline Cluster Surveys. Global Public Health. 2013;8(3):284-297. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17441692.2012.758302.

- Ninsiima LR, Chiumia IK, Ndejjo R. Factors Influencing Access to and Utilisation of Youth-Friendly Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Reproductive Health. 2021;18(1). Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-021-01183-y.

- Population Services International (PSI) Support for International Family Planning and Health Organizations 2: Sustainable Networks (SIFPO2) April 2014 – December 2020, SIFPO2 Year Six Semi-annual Report October 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00XCW3.pdf

- MSI Reproductive Choices. Evidence and Insights, Version 2. London: MSI Reproductive Choices; 2022. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.msichoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/msi-evidence-insights-compendium-2022.pdf.

- Kifle, YA, Nigatu, TH. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Clinical Specialist Outreach as Compared to Referral System in Ethiopia: An Economic Evaluation. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2010;8(1):13. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://resource-allocation.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-7547-8-13.

- Nwakamma IJ, Talla CS, Kei SE, Okoro GC, Asuquo G, Onu KA. Adolescent and Young People’s Utilization of HIV/Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: Comparing Health Facilities and Mobile Community Outreach Centers. International Journal of Translational Medical Research and Public Health. 2019;3(2):66-74. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://ijtmrph.org/adolescent-health-adolescent-and-young-peoples-utilization-of-hiv-sexual-and-reproductive-health-services-comparing-health-facilities-and-mobile-community-outreach-centers/.

- Teklemariam, E, Getachew S, Kassa S, Atomsa W, Setegn M. What Works in Family Planning Interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review. Journal of Women’s Health Care. 2019;8(4):1-6. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.longdom.org/open-access/what-works-in-family-planning-interventions-in-subsaharan-africa-a-scoping-review-44642.html.

- Ngo TD, Nuccio O, Reiss K, Pereira SK. Expanding Long-Acting and Permanent Contraceptive Use in Sub-Saharan Africa to Meet FP2020 Goals. London: Marie Stopes International; 2013 November. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272481159_Expanding_long-acting_and_permanent_contraceptive_use_in_sub-Saharan_Africa_to_meet_FP2020_goals.

- Hayes G, Fry K, Weinberger M. Global Impact Report 2012: Reaching the Under-Served. London: Marie Stopes International; 2013. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20131219185830/http://www.mariestopes.org/sites/default/files/Global-Impact-Report-2012-Reaching-the-Under-served.pdf.

- Thapa S, Friedman M. Female Sterilization in Nepal: A Comparison of Two Types of Service Delivery. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 1998;24. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/journals/ipsrh/1998/06/female-sterilization-nepal-comparison-two-types-service-delivery.

- Aruldas K, Khan ME, Ahmad J, Dixit A. Increasing Choice of and Access to Family Planning Services Via Outreach in Rajasthan, India. New Delhi: Population Council; 2014. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/955/.

- Yakubu I, Salisu WJ. Determinants of Adolescent Pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Reproductive Health. 2019;15(1). Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-018-0460-4.

- Dioubaté N, Manet H, Bangoura C, Sidibé S, Kouyaté M, Kolie D, Ayadi AME, Delamou A. Barriers to Contraceptive Use Among Urban Adolescents and Youth in Conakry, in 2019, Guinea. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health. 2021;2. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/global-womens-health/articles/10.3389/fgwh.2021.655929/full.

- Solo J, Festin M. Provider Bias in Family Planning Services: A Review of Its Meaning and Manifestations. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2019;7(3):371-385. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from:

https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/early/2019/09/12/GHSP-D-19-00130/tab-figures-tables?versioned=true. - Jones B. Mobile Outreach Services: Multi-Country Study and Findings from Tanzania. New York: The RESPOND Project/EngenderHealth; 2011. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20170517095443/https://www.respond-project.org/pages/files/5_in_action/lapm-cop-mobile-services/Barbara-Jones.pdf.

- Weidert K, Tekou KB, Prata N. Quality of Long-acting Reversible Contraception Provision in Lomé, Togo. Open Access Journal of Contraception. 2020; 11:135-145. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7520155/.

- Population Services International. Support for International: Family Planning and Health Organizations 2. Washington, DC: Population Services International; 2021. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://media.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/30234640/SIFPO2-Report.pdf.

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Family Planning and Immunization Integration: Reaching Postpartum Women With Family Planning Services. Washington, DC: USAID; 2021 September. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/family-planning-and-immunization-integration/.

- Ideas 42 and Maria Stopes International, Maria Stopes Uganda. Confronting Concerns About Family Planning Methods: Increasing Sustained Use of LARCs in Uganda. New York: Ideas 42; 2020 October. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.ideas42.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/I42-1261_dBiasProgram_Brief_2.pdf.

- Chowdhury R. Choice in Her Hands: Challenging Provider Bias to Support Reproductive Self-Care. Washington, DC: Population Services International; 2021 January. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.psi.org/project/self-care/choice-in-her-hands-challenging-provider-bias-to-support-reproductive-self-care/.

- Temba A, Gamaliel J, Njelekela M, et al. “One Stop Shop” Mobile Family Planning Outreach and Service Integration in Southern Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: EngenderHealth Tanzania; 2024. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://d1c2gz5q23tkk0.cloudfront.net/assets/uploads/3082411/asset/EngenderHealth_Tanzania.pdf?1618608657.

- High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Community Health Workers: Bringing Family Planning Services to Where People Live and Work. Washington, DC: USAID; 2015. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/community-health-workers.

- Berger G, Aresu A, Newnham J. Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for All: Disability Inclusion from Theory to Practice. Silver Spring, MD: Humanity & Inclusion. 2022. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://www.hi-us.org/sn_uploads/document/1288_HI_Guidelines_17_10_22_DIGITAL.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Task Sharing to Improve Access to Family Planning/Contraception. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259633/WHO-RHR-17.20-eng.pdf.

- USAID. Voluntarism and Informed Choice. Washington, DC: USAID; 2023. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20250131213444/https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-areas/family-planning/voluntarism-and-informed-choice.

- Dumas EF, Hama D, Moon P, Saley M, Thurston S, Wilson M. Mobile Outreach for Family Planning in Rural Niger: Delivering and Adapting High Impact Practices in Fragile and Hard-to-Reach Settings. Washington, DC: Population Services International; 2019 December. Accessed March 14, 2025. Available from: https://media.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/31005039/Brief-Niger-English1.pdf.

- Abdel-Tawab N, RamaRao S. Do improvements in client–provider interaction increase contraceptive continuation? Unraveling the puzzle. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;81(3):381-387. Accessed March 14, 2025, Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21074962/