Community Health Workers: Bringing Contraceptive Information and Services to People Where They Live and Work

Background

Community health workers (CHWs) are health care providers who have less formal education than professionals such as nurses and doctors and offer an increasingly broad range of health services to communities, often their own.1 CHWs frequently serve as people’s first point of contact with health systems; as such, they are essential actors in local, national, and global efforts to expand knowledge of, access to, and use of modern contraception. By bringing relevant information, services, and supplies to people where they live and work, CHWs play particularly important roles in extending the reach of public sector family planning services in areas where unmet need is high, access is low, and there are geographic or social barriers to use of family planning services.2 As evidenced during the COVID-19 pandemic, CHWs are a first line of defense in times of crisis, given their increased access to and embeddedness in communities.2,3

By systematically selecting and training CHWs and providing them with sustainable financial, administrative, and regulatory support, national health systems can extend benefits of CHWs to large populations and improve overall equity in knowledge of and access to health care, including family planning.1,4,5,6

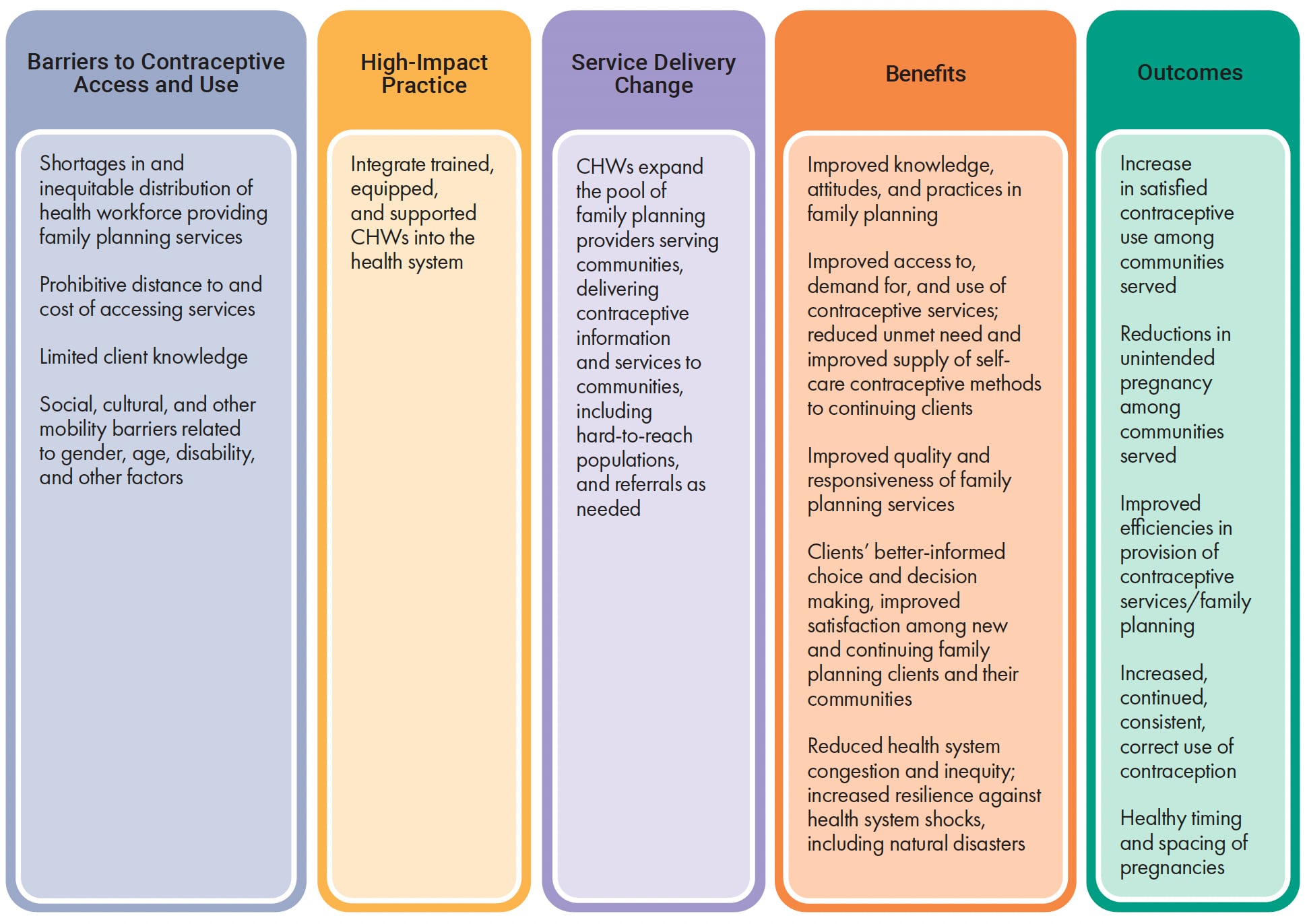

This brief focuses on benefits and impacts of well-managed, large-scale, public sector CHW initiatives in family planning. Integrating CHWs into the health system is one of several proven High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs) identified by a technical advisory group of international experts. For more information about other HIPs, see https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/.

What challenges can CHWs help countries address?

CHWs help health systems address geographic access barriers caused by health worker shortages.

The World Health Organization projects a shortfall of 10 million health workers by 2030, mainly in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Employing CHWs has emerged as one of the most effective ways to address shortages of human resources for health, expand health system reach, and improve access to and quality of primary health care.1,7 In rural, hard-to-reach settings with health worker shortages, CHWs can be at least as effective as standard facility-based services in increasing contraceptive prevalence and use.8–11 Bringing family planning services closer to clients reduces both cost and geographic barriers.

Appropriately trained and supported CHWs address clients’ gaps in knowledge about modern contraception.

CHWs are critical resources in providing education and counseling on contraceptive choices, addressing myths and misconceptions about family planning, and answering questions or concerns about side effects.1,10,12,13 They help guide clients to select contraceptive methods and provide referrals to health care facilities for provider-initiated contraceptive methods (such as an intrauterine contraceptive device or permanent contraception) and for medical care.

CHWs can effectively address young people’s needs for contraception and other sexual and reproductive health information and care.

A systematic review of qualitative studies in sub-Saharan Africa identified numerous personal, societal, and health systems-based barriers to contraceptive use among young people. These include myths and misconceptions about contraceptive methods and their side effects, restrictive social norms and stigma among health care professionals related to adolescent sexuality (especially among unmarried women and girls), and negative attitudes toward adolescent contraceptive use.14 CHWs play a key role in health promotion among youth by providing information, counseling, and guidance on overall sexual and reproductive health that can boost health service utilization, uptake of short-acting methods, and contraceptive continuation.2,12,15,16 In the Uttar Pradesh state in India, for example, training, mentoring, and otherwise supporting CHWs on addressing the family planning needs of young, married, first-time parents significantly increased exposure to family planning information and use of modern contraceptives among this group, whose unmet need is traditionally high.17

CHWs can help overcome social, cultural, and physical barriers that inhibit contraceptive use among people living with disabilities, gender and ethnic minorities, and other disenfranchised communities.

CHWs from disenfranchised communities provide a bridge to the health system by bringing, in a culturally appropriate manner, sexual and reproductive health information, counseling, and services to people where they work and live. At the same time, these CHWs help boost trust in and engagement with the health system, health service utilization, and uptake of contraceptive methods.2,15,16,18 In Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sierra Leone, community-based mobilizers recruited from local organizations of persons with disabilities effectively reached members of their community with sexual and reproductive health-related information and care, including family planning.19 In some countries, women’s movements and independent decision making are constrained by social norms. CHWs have worked around these cultural barriers by bringing services directly to where women and their families live and work. CHWs’ engagement in communities also positions them to identify high-need populations who may not seek family planning or other health care services, such as pregnant adolescents, new mothers at risk of repeat pregnancy, and migrant populations.

CHWs are instrumental in providing care during pandemics and in humanitarian and other emergency settings when access to clinic-based care is limited.20

Case studies in Kenya and Nigeria illustrated the front-line work of trained youth community health volunteers in sustaining access to family planning services and increasing use of contraceptive self-injection among adolescents and youth during COVID-19 restrictions.2 CHWs’ presence in communities facilitated their ability to reach clients who were subject to restrictions on movement and gatherings.

What is the impact?

The Appendix summarizes key studies referenced below on the impact of CHWs in providing family planning information and services.

Appropriately trained and supported CHWs help improve knowledge and attitudes related to contraception.

Counseling by CHWs has been associated with improved knowledge and more positive attitudes toward family planning among clients and communities, as well as increased likelihood of contraceptive uptake and continuation.1,10,12,13 Counseling and referrals by CHWs is also positively associated with greater acceptability and high client satisfaction with injectables, implants, and other hormonal contraception methods.8,11,21,22

CHWs help increase both initial uptake and continued use of modern contraceptive methods, including long-acting methods.

In northern Nigeria, trained and supported CHWs mobilized community members in support of family planning, generated demand, and safely inserted contraceptive implants while providing high-quality counseling to clients.21 In rural Nigeria, contact with CHWs significantly increased women’s intention to use modern contraception.23 Researchers in Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, and Uganda observed contraceptive continuation rates of 47% to 96% at three, six, and 12 months after the first injection of DMPA (depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate), also known as Depo-Provera, by CHWs.8,9,12

CHW programs increase contraceptive use in places where use of clinic-based services is not universal.

CHWs’ engagement in providing home-based antenatal and postnatal care enables them to reach women with information regarding postpartum family planning, which has been shown to increase contraceptive use among postpartum women.11,24–26

CHWs working in coordination with a functioning health system reduce unmet need for contraception and help couples and individuals accomplish their reproductive intentions.

A community-based health delivery program in Madagascar that deployed CHWs to provide family planning services increased women’s likelihood of ever using a contraceptive method and reduced the probability of conception by 12%.27 In Burkina Faso, a task sharing program that trained and supported CHWs to provide long-acting and reversible methods reported a tripling of acceptance of such methods in just six months, averting 11.7% of expected pregnancies in 2019; in Ethiopia, such task sharing contributed to doubling the contraceptive prevalence rate and declining rates of total fertility.28 Another study in Ethiopia found that exposure to well-qualified health extension workers decreased women’s unmet need for family planning, increasing both their demand for and use of contraceptive methods.29

CHWs expand clients’ choices of contraceptive methods by providing a wide range of methods safely and effectively.

Evidence supports trained and supported CHWs’ ability to safely and effectively counsel, refer, and provide clients in low- and middle-income country settings with both short- and long-acting and reversible family planning methods, including injectable contraceptives, and contraceptive implants.8,9,21,22,28,30 Research in Malawi showed that CHWs can effectively train women in rural settings to self-inject subcutaneous DMPA, with no difference in continuation rates for clients trained by CHWs versus clinic-based providers.30,31 In Burkina Faso, Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, Uganda and elsewhere, CHWs effectively trained women to self-inject. They also provided follow-up care, including support in managing complications and side effects, with positive impact on continuation rates.9,31,32

CHWs can help reduce inequities in knowledge of and access to services, by effectively serving disadvantaged, remote, and otherwise hard-to-reach segments of populations.

A systematic review found that CHW programs in low- and middle-income countries promote equity of access and service utilization, addressing barriers related to place of residence, gender, education, socioeconomic status, and other factors.5 Further reviews suggested that, in particular, CHWs’ home visits and facilitation of participatory women’s groups reduced inequities in coverage, access to services, and health behaviors related to maternal and newborn health. This in turn had the effect of expanding the scope of CHWs’ remits, ensuring strong training and monitoring and effective partnerships between CHWs and other stakeholders, and addressing financial barriers that impede clients’ ability to heed CHWs’ advice and referrals.4,33

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

- Recruit CHWs from and embed them within communities. Communities’ sense of ownership in CHW programs, derived from having substantial control over CHWs’ selection, promotion, monitoring, and activities, is associated with higher program success, including CHW retention and performance.1 Effective community engagement in CHW programs entails pre-consultation with community leaders and community participation in evidence-based needs assessments, selecting and monitoring CHWs, choosing and prioritizing CHW activities, decision making, problem solving, planning, and budgeting for CHW programs.34

- Link CHWs to the health system with well-defined referral structures. Health referral systems need to be strengthened to ensure that CHWs can not only refer clients to health facilities, at all appropriate levels, but also get feedback after service delivery elsewhere to ensure continuum of care. The focus, however, should be to ensure essential services at the community level with robust referrals for more complex services.

- Empower CHWs to contribute to national health management information systems (HMIS). Modify national HMIS to gather cadre-specific data on family planning to ensure accurate measurement of CHWs’ contributions. Ensure that CHWs understand and have the necessary tools (including digital), skills, and time for accurate reporting into the HMIS, as well as for timely and appropriate interpretation and use of data, to optimize data and product flow between CHWs and the larger health system.

- Ensure that CHWs’ voices are heard through representation in relevant health planning and policymaking bodies. Comprehensive integration of CHW programs and personnel into national health care planning, governance, and financing is essential to optimize CHWs’ performance and impact.1 It is vital to include CHWs in community, facility, and national governance and decision-making structures.

- Implement a comprehensive training program that includes incremental, practical, competency-based training on the full range of contraceptive methods, with regular refresher training, especially on emerging trends such as self-care, best practices, and technical approaches. Build on existing curricula and other tools to enhance integration and sustainability. Effective training addresses clinical aspects of method provision and follow-up care, including helping clients manage side effects; skills in social and behavior change, such as counseling and interpersonal communication and behavior-change communication; and ethical conduct.1,35,36 In South Sudan, low-dose, high-frequency training led to higher satisfaction among CHWs. It also was credited with better retention and greater application of new knowledge and skills in family planning and other aspects of maternal and newborn care than with traditional training and supervision approaches.37

- Use digital technology to enhance training, data collection, and post-training support to CHWs. Integration of CHW training on contraceptive counseling into mobile applications has led to increased uptake of contraception methods.38,39 In Nepal, a multi-village intervention used mobile technology to collect data and display counseling content to support CHWs in delivering patient-centered, home-based antenatal and postnatal counseling on postpartum contraception. Through knowledge transfer, demand creation, referrals to health facilities, and follow-up, the intervention increased modern contraceptive use from 29% among recently postpartum women to 46% of them.11

- Invest attention and funding to improve supply chains and ensure regular provision of the broadest possible mix of contraceptive methods and related commodities to CHWs. Continuous availability of contraceptive supplies at the community level is essential to maintain CHWs’ motivation, program effectiveness, and community trust, and to achieve overall program success.1 Although not specific to family planning, studies in Malawi and Rwanda showed that establishing multilevel quality-improvement teams to support the use of streamlined, demand-based resupply procedures by CHWs and other providers significantly reduces bottlenecks and improves community-level availability of essential commodities.40 Governments should consider revising policies to authorize CHWs to provide the broadest possible range of contraceptive methods, as supported by evidence.

- Professionalize CHWs’ status within the health system through national policy. Formalize CHWs’ relationships to the government or local non-governmental organizations with written contracts that specify CHWs’ roles and duties, working conditions, remuneration, rights, and how their work integrates with that of other health care workers and with the community. Create clear pathways for long-term career progression, including certification to visibly recognize CHWs’ contributions and to drive quality standards for training and performance, and transition to retirement.34 Ensure that CHWs enjoy the same benefits as other health care employees, including health insurance, retirement benefits, and coverage by labor protection laws.

- Effectively implement task sharing. Training and supporting CHWs to take on family planning tasks that traditionally have been assigned to higher cadres of providers have proven effective in a variety of settings in increasing clients’ access to services without diminishing quality of care.28 Clear, comprehensive task sharing and task shifting policies and guidelines that formalize CHWs’ authority and duties are essential to effective task work, including countering resistance among other cadres of health care workers.40

- Implement supportive supervision. Effective coaching, mentoring, and supportive supervision of CHWs can be done by facility-based providers and established structures such as local health units.41 Ensuring manageable workload is especially important because increased task sharing and task shifting, when added to CHWs’ duties, may adversely affect morale, performance, and retention. Consider pairing CHWs to help ensure continuity of services in the event of turnover.

- Strengthen political leadership and domestic funding for CHW programs. Multisectoral, shared ownership, and collaboration among communities, governments, and other stakeholders at all levels are critical to the success of CHW programs. An effective enabling and policy environment includes clear authorization and guidance for appropriately trained CHWs to provide a wider range of family planning services and methods. Strong leadership that prioritized community-based family planning services has been essential to effective CHW programs such as Nigeria’s health extension workers, currently the country’s main providers of family planning services including long-acting and reversible methods of contraception.25,28 Documenting the impact of CHW programs and using evidence of their success can be useful for advocacy purposes, including securing necessary financial resources.

Planning, Implementing, and Scaling-Up CHW Programs in Family Planning

| Program Considerations | Factors Contributing to Success | Factors Contributing to Failure | Considerations for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Approach | Understanding that CHW programs are complex and challenging to sustain. | Misconception that CHW programs are simple and self-sustaining. | Plan for scale-up from the beginning. Make a systematic plan for scale-up based on country strategy and existing program. |

| Range of Services and Commodities | Broad range of services and commodities that reflect preferences of communities served, as identified by needs assessment. A well-functioning supply chain to ensure timely, reliable availability of clients’ preferred methods and necessary supplies. | Preoccupation with a single commodity or service resulting in failure to develop a comprehensive service system. Stockouts threaten support for and reputation of CHWs. | Adapt service package to meet a community’s evolving needs. Ensure dependable national-level availability of commodities, equipment, and supplies for defined needs and a supply chain that facilitates efficient movement of products to resupply points as well as data to and from all levels of the system. |

| Community Engagement & Political Support | Community engagement at all stages, from strategic planning through implementation, monitoring, and evaluation, and continuous program improvement. CHW selection guided by community opinion. Ownership and collaboration with government and key stakeholders at all levels. | Lack of community buy-in and broad political support. Responsibility of galvanizing and mobilizing communities rests solely with CHWs. | Sustain engagement of community and health system with leadership from district and health center staff. Ensure local and national political support, including policies and mechanisms to support timely program adaptation in response to identified needs. |

| Sustainability vs. Compensation | Paid workers perform better than volunteers. Completely voluntary schemes do not work well. If workers are not paid, some other motivational scheme is required, and the scope of work for unpaid volunteers should be realistic. |

Overemphasis on sustainability and cost recovery, which may be incompatible with the objective of reaching poor and remote communities. | Advocate with governments, donors, and community for political and financial support. Provide cost-benefit information. When planning the program, consider costs of scaling-up as well as of maintaining the program at scale. |

| Training | Competency-based training for CHWs in counseling and method provision. Consider regular refresher training, including low-dose, high-frequency approaches; use of mobile technologies; and ongoing coaching and mentorship. | Infrequent training without ongoing follow-up or support. | Leverage existing policies on task shifting to provide on-the-job training and supervision. |

| Quality of Care | Clear definition of and consistent emphasis on quality of care at every stage: planning, training, monitoring and evaluation. | Failure to overtly and consistently address quality of care negatively affects trust in, use of, and overall effectiveness of the program. | Improve quality continuously through active organizational management. Address broad contextual and health system barriers. |

| Social Barriers | CHWs trained and engaged in social and behavior change communication activities. CHWs recruited from and/or trained to effectively engage with marginalized communities. | Failure to address social barriers to contraceptive use. | Co-design programs with members of communities commonly affected by social barriers. |

| Supervision of CHWs | Supportive, rather than directive, CHW supervision. | Lack of connection with larger health system. | Consider mobile technologies and other innovations to support remote case management. |

| Health Management Information Systems | Health management information systems that support the information needs of CHWs and include simple and effective data collection mechanisms linked to the health system. | Failure to collect, coordinate, and use data on health service use threatens program functioning and impact. | Consider SMS and web-based mHealth systems, where data is transformed into relevant, usable reports and shared on a timely basis. |

| Referrals & Linkages | CHWs are linked to and have ongoing relationships with facility-based services. | CHW system is viewed as separate from the health system. | Ensure referral and linkage systems from CHWs to the health facility are in place and clearly understood by CHWs. Strengthen relationship between CHWs and health care providers. |

Implementation measurement

Integrating community health workers into the health care system has demonstrated benefits in family planning. The following indicators may be helpful in measuring implementation and outcomes:

- Percent of clients reporting that they received family planning information and services from a CHW in the past 12 months (reporting age- and gender-disaggregated data)

- Number/percent of CHWs’ completed referrals to health care facilities for family planning services

- Number/percent of CHWs who received new or in-service training/professional development in provision of high-quality family planning services

- cStock. A RapidSMS, open-source, web-accessible logistics information management system that helps CHWs and health centers streamline reporting and resupply of up to 19 health products, including contraceptives, managed at the community level while enhancing communication and coordination among CHWs, health centers, and districts.

- WHO Guideline on Health Policy and System Support to Optimize Community Health Worker Programmes. This guideline identifies the policy and systems enablers to assist governments and partners improve the design, implementation, performance, and evaluation of CHW programmes.

- Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement Matrix (CHW AIM). A tool to identify design and implementation gaps in both small- and national-scale CHW programs and to close gaps in policy and practice.

- Task Sharing to Improve Access to Family Planning/Contraception. Summary of recommendations to provide capacity to lay and mid-level health care professionals including CHWs to safely provide clinical tasks and procedures that would otherwise be restricted to higher-level cadres.

Priority research questions

Because CHWs are often people’s first point of contact with health systems, it’s important that CHW programs are set up in the best way to serve an individual community. Key research questions include:

- What program implementation strategies are needed to ensure the quality of family planning services when integrated alongside other services provided by CHWs?

- How do different models of remuneration for CHWs compare in terms of impact on motivation, performance, retention, and cost-effectiveness?

- How do the cost-effectiveness and sustainability of delivering family planning services through CHWs compare with clinic-based care and other models?

- How does gender influence the effectiveness and accessibility of community health workers in delivering health services to underserved populations?

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Community Health Workers: Bringing Contraceptive Information and Services to People Where They Live and Work. Washington, DC: HIP Partnership; Month Year. Available from https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/community-health-workers/

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by: Afua Aggrey (USAID/Ghana), Mojisola Alere (DAI Nigeria), Khadija Swalehe Ally (Community Hands Foundation Tanzania), Pritha Biswas (Independent), Sarah Castle (Independent), Sanjeeta Gawri (IPE Global Limited), Asante Kamuyango (WHO), Ronald Kibonire (Save the Children), Christopher Kuria (Action for Community Development Center Kenya), and Merrill Wolf (Independent). It was updated from a previous version, published in 2015, available here https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/previous-brief-versions/

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Maria Carrasco (USAID), Emeka Nwachukwu (USAID), Erin Milke (USAID), Mackenzie Schiff (Palladium), Anand Sinha (Packard Foundation), Janelli Vallin (Innovations for Choice and Autonomy at the University of California San Francisco), Peter Kibor Keitany (Belgian Red Cross Flanders Uganda), and Ados May (WHO/IBP Network).

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception.

References

- World Health Organization. What Do We Know About Community Health Workers? A Systematic Review of Existing Reviews. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 April. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/what-do-we-know-about-community-health-workers-a-systematic-review-of-existing-reviews.

- Malkin M, Mickler AK, Ajibade TO, et al. Adapting High Impact Practices in Family Planning During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences From Kenya, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2022;10(4). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9426984/.

- Salve S, Raven J, Das P, et al. Community Health Workers and COVID-19: Cross-Country Evidence on Their Roles, Experiences, Challenges and Adaptive strategies. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023;3(1): e0001447. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10022071/.

- Ahmed S, Chase LE, Wagnild J, et al. Community Health Workers and Health Equity in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Systematic Review and Recommendations for Policy and Practice. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2022;21(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-021-01615-y.

- McCollum R, Gomez W, Theobald S, et al. How Equitable are Community Health Worker Programmes and Which Programme Features Influence Equity of Community Health Worker Services? A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-016-3043-8.

- World Health Organization. Community Health Workers: A Strategy to Ensure Access to Primary Health Care Services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/EMROPUB_2016_EN_1760.pdf.

- Evans M, Andréambeloson T, Randriamihaja M, et al. Geographic Barriers to Care Persist at the Community Healthcare Level: Evidence from Rural Madagascar. PLOS Global Public Health. 2022;2(12): e0001028. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0001028.

- Ayuk BE, Yankam BM, Saah FI, & Bain LE. Provision of Injectable Contraceptives by Community Health Workers in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of Safety, Acceptability, and Effectiveness. Human Resources for Health. 2022;20(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12960-022-00763-8.

- MacLachlan E, Atuyambe LM, Millogo T, et al. Continuation of Subcutaneous or Intramuscular Injectable Contraception When Administered by Facility-Based and Community Health Workers: Findings From a Prospective Cohort Study in Burkina Faso and Uganda. Contraception. 2018;98(5):423–429. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6197835/.

- Scott VK, Gottschalk LB, Wright, KQ, et al. Community Health Workers’ Provision of Family Planning Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of Effectiveness. Studies in Family Planning. 2015;46(3):241–261. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281608068_Community_Health_Workers%27_Provision_of_Family_Planning_Services_in_Low-_and_Middle-Income_Countries_A_Systematic_Review_of_Effectiveness.

- Wu, WJ, Tiwari A, Choudhury N, et al. Community-Based Postpartum Contraceptive Counselling in Rural Nepal: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2020;28(2):1765646. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/26410397.2020.1765646.

- Lemani C, Tang JH, Kopp D, et al. Contraceptive Uptake After Training Community Health Workers in Couples Counseling: A Cluster Randomized Trial. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(4): e0175879. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0175879.

- UNICEF, Oxford Policy Management, Ministry of National Health Services, Regulation and Coordination. Lady Health Workers Programme, Pakistan: Performance Evaluation. New York: UNICEF; 2019 September. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/media/3096/file/Performance%20Evaluation%20Report%20-%20Lady%20Health%20Workers%20Programme%20in%20Pakistan.pdf.

- Bain LE, Amu H, Tarkang EE. Barriers and Motivators of Contraceptive Youth Among Young People in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(6): e0252745. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0252745.

- Mulligan B, Ribaira GY, Rossi EE, Gottert P. Linking CHVs, Youth and Community Members to Increase Family Planning Services. Boston: CHW Central. 2022 May. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://chwcentral.org/linking-chvs-youth-and-community-members-to-fps/.

- Brooks MI, Johns NE, Quinn AK, et al. Can Community Health Workers Increase Modern Contraceptive Use Among Young Married Women? A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural Niger. Reproductive Health. 2019;16(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-019-0701-1.

- Sharma MK, Das E, Sahni H, et al. Engaging Community Health Workers to Enhance Modern Contraceptive Uptake Among Young First-Time Parents in Five Cities of Uttar Pradesh. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2024;12(Suppl 2): e2200170. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/12/Supplement_2/e2200170.

- Perry HB, Chowdhury AMR. Bangladesh: 50 Years of Advances in Health and Challenges Ahead. Global Health, Science and Practice. 2024;12(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10906562/.

- MSI Reproductive Choices. Committed to Leaving No One Behind: Contributions of the WISH Programme to Increasing Disability Inclusive Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in West and Central Africa. London: MSI Reproductive Choices. 2023 December. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.msichoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/MSI-WISH-Disability-Inclusion-Report-December-2023.pdf.

- Rab F, Razavi D, Kone M., et al. Implementing Community-Based Health Program in Conflict Settings: Documenting Experiences from the Central African Republic and South Sudan. BMC Health Services Research. 2023;23(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-023-09733-9.

- Charyeva Z, Oguntunde O, Orobaton N, et al. Task Shifting Provision of Contraceptive Implants to Community Health Extension Workers: Results of Operations Research in Northern Nigeria. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2015;3(3):382–394. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/3/3/382.

- Weidert K, Gessessew A, Bell S, Godefay H, & Prata N. Community Health Workers as Social Marketers of Injectable Contraceptives: A Case Study from Ethiopia. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2017;5(1):44-56. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/5/1/44.

- Solanke BL, Oyediran OO, Awoleye AF, Olagunju OE. Do Health Service Contacts with Community Health Workers Influence the Intention to Use Modern Contraceptives Among Non-Users in Rural Communities? Findings From a Cross-Sectional Study in Nigeria. BMC Health Services Research. 2023;23(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9832820/.

- MCSP (Maternal and Child Survival Program), USAID. Community-Based Family Planning Breaking Barriers to Access and Increasing Choices for Women and Families. Washington, DC: USAID; 2019 December. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.mcsprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/5_-MCSP-CBFP-Brief.pdf.

- Perry, HB. Health for the People: National Community Health Worker Programs from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Boston: CHW Central. 2021 October. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://chwcentral.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Health_for_the_People_Natl_Case%20Studies_Oct2021.pdf.

- Sitrin D, Jima GH, Pfitzer A, et al. Effect of Integrating Postpartum Family Planning into the Health Extension Program in Ethiopia on Postpartum Adoption of Modern Contraception. Journal of Global Health Reports. 2020;4. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.joghr.org/article/13511-effect-of-integrating-postpartum-family-planning-into-the-health-extension-program-in-ethiopia-on-postpartum-adoption-of-modern-contraception.

- Herrera-Almanza C, Rosales-Rueda MF. Reducing the Cost of Remoteness: Community-Based Health Interventions and Fertility Choices. Journal of Health Economics. 2020; 73:102365. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167629619309452.

- Ouedraogo L, Habonimana D, Nkurunziza T, et al. Towards Achieving the Family Planning Targets in the African Region: A Rapid Review of Task Sharing Policies. Reproductive Health. 2021;18(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-020-01038-y.

- Tadesse D, Medhin G, Kassie GM, et al. Unmet Need for Family Planning Among Rural Married Women in Ethiopia: What Is the Role of the Health Extension Program in Reducing Unmet Need? Reproductive Health. 2022;19(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-022-01324-x.

- Tilahun Y, Lew C, Belayihun B, Lulu Hagos K, Asnake M. Improving Contraceptive Access, Use, and Method Mix by Task Sharing Implanon Insertion to Frontline Health Workers: The Experience of the Integrated Family Health Program in Ethiopia. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2017;5(4):592-602. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/5/4/592.

- Burke HM, Chen M, Buluzi M, et al. Effect of Self-Administration Versus Provider-Administered Injection of Subcutaneous Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate on Continuation Rates in Malawi: A Randomised Controlled Trial. The Lancet Global Health, 2018;6(5): e568-e578. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(18)30061-5/fulltext.

- Burke HM, Chen M, Buluzi M, et al. Factors Affecting Continued Use of Subcutaneous Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (DMPA-SC): A Secondary Analysis of a 1-Year Randomized Trial in Malawi. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2019;7(1):54–65. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/7/1/54.

- Blanchard AK, Prost A, Houweling TAJ. Effects of Community Health Worker Interventions on Socioeconomic Inequities in Maternal and Newborn Health in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4(3): e001308. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/4/3/e001308?int_source=trendmd&int_medium=cpc&int_campaign=usage-042019.

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline on Health Policy and System Support to Optimize Community Health Worker Programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/275474/9789241550369-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). SBC Overview: Integrated Framework for Effective Implementation of the Social and Behavior Change High Impact Practices in Family Planning. Washington, DC: HIP Partnership; 2022 August. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/sbc-overview/.

- Alam D, Pal M, Kaushik S, Singal S, Agarwal A. Enhancing Community-Based Family Planning Using a Train–Assist–Graduate Framework: Supporting Accredited Social Health Activists to Facilitate Voluntary, Informed Decisions. Washington, DC: EngenderHealth. 2021. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.engenderhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/imported-files/Enhancing-Community-Based-Family-Planning-Using-a-Train%E2%80%93Assist%E2%80%93Graduate-Framework.pdf.

- USAID, World Relief. Scope: Community Health Workers Technical Brief. Washington, DC: USAID; 2024. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://worldrelief.org/content/uploads/2024/03/SCOPE-CHW-Technical-Brief.pdf.

- E2A (Evidence to Action), USAID. Strengthening Community-Based Family Planning Services in Shinyanga, Tanzania. Washington DC: USAID; 2015 October. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.pathfinder.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Tanzania-Strengthening-CBFP-Services.pdf.

- Eyapu A, Namugera F, Katushabe P. Digital Health Pilot Project in Uganda Extends the Reach of Family Planning Care in the Community. Baltimore: Knowledge Success. 2021 January. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://knowledgesuccess.org/2021/01/15/digital-health-pilot-project-in-uganda-extends-the-reach-of-family-planning-care-in-the-community/.

- Chandani Y, Duffy M, Lamphere B, Noel M, Heaton A, Andersson S. Quality Improvement Practices to Institutionalize Supply Chain Best Practices for iCCM: Evidence from Rwanda and Malawi. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy. 2017;13(6):1095-1109. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://chwcentral.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Quality-improvement-practices-to-institutionalize-supply-chain-best-practices-for-iCCM.pdf.

- Okoroafor SC, Christmals CD. Task Shifting and Task Sharing Implementation in Africa: A Scoping Review on Rationale and Scope. Healthcare. 2023;11(8):1200–1200. Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10138489/.

- Hill Z, Dumbaugh M, Benton L. (2014). Supervising Community Health Workers in Low-Income Countries: a Review of Impact and Implementation Issues. Global Health Action, 7(1). Accessed April 30, 2025. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24815075/.