Social Marketing: Using marketing principles and techniques to improve contraceptive access, choice, and use

Background

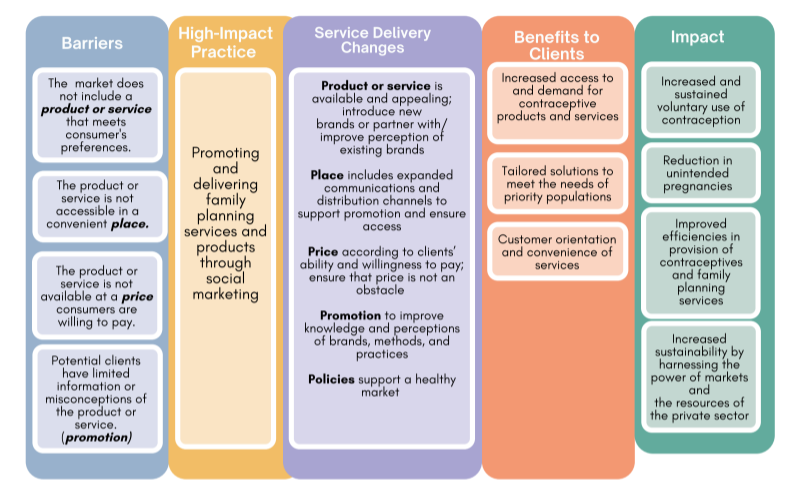

Social marketing seeks to leverage marketing concepts to influence behaviors that benefit individuals and communities for the greater social good.1 It uses behavior change theory, market research, and consumer insight to inform the delivery of health information, products, and services that are attuned to client’s needs, values, and preferences. To do so, social marketing defines its program objectives and utilizes the following four foundational elements of marketing (i.e., the 4 Ps: product, price, promotion, and place) to develop strategies to achieve them. There is growing recognition of the importance of policy in supporting the 4Ps. The 4Ps plus policy can be defined as follows2,3:

- Product: a good or service offered to a specific market segment or priority group.

- Price: clients’ willingness or ability to pay, considering financial and opportunity costs and competition with other similar products.

- Promotion: communication and/or advertising about the product or service targeted to the market segment or priority group.

- Place: availability and distribution channels to reach the target market segment, linked to promotion channels.

- Policy: policy revision, adoption, and/or guidance to ensure a healthy market.

Social marketing success is ultimately about creating sustained behavior change, which goes beyond changing knowledge and attitudes around family planning. What distinguishes social marketing from other behavior change approaches is the notion of value exchange, or the idea that the target audience will adopt or select—a contraceptive method, product, or service—in exchange for perceived benefits.

This notion is rooted in commercial marketing and is evidenced by the many daily consumer behavior decisions we make to purchase one product/service/brand over another due to perceived benefits such as efficacy, value for money, brand status, and improved health. Marketing offers a useful lens through which program designers can leverage the cost/benefit, risk/reward, and incentive/disincentive calculations made by consumers in everyday decision making as they design family planning strategies that create value in the mind of the client and reduce barriers to access.

In addition to promoting behavior change, social marketing programs are also designed to expand the range of contraceptive options available and/or increase when, how, and from whom clients can obtain methods and services (for further information of related HIP briefs to increase access, see: Community Health Workers, Pharmacies and Drug Shops, Social Franchising HIP briefs). Social marketing can serve as a bridge to developing a commercial market in a nascent context where family planning use is relatively low or where the public sector is the dominant source for family planning products and services. Social marketing programs can also work in harmony with an existing commercial market if strategies (e.g., for target market segments and pricing), plans, and relevant stakeholders are coordinated. An ideal family planning marketplace includes a range of actors offering consumers choices of high-quality family planning products at different price points and locations. Such a marketplace can reduce the burden on the public sector by shifting clients who can pay commercial or subsidized prices to private sector sources of family planning. When governments support and invest in strengthening and diversifying the market that comprises the health system, they facilitate opportunities for greater resilience of family planning access and method choice. Governments should provide stewardship—through supportive policies, leadership, and coordination—to ensure that public sector, social marketing, and commercial actors are respectively reaching the desired targeted segments of the population and are able to succeed in the market and meet users’ needs.

Social marketing is one of several proven “high-impact practices” (HIPs) in family planning identified by the HIP partnership and vetted by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. When scaled up, HIPs maximize investments in a comprehensive family planning strategy. For more information about HIPs, see http://www. fphighimpactpractices.org/overview.

What challenges can this practice help us address?

Low demand for contraception. A social marketing program can increase demand for contraceptives by addressing individual knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs, as well as social and community norms. Through integrated, evidence-based behavior change campaigns, social marketing programs can promote the benefits of contraceptive use, ensuring that contraceptives are easily available and that people want to use them.4,5

Limited access to high-quality and affordable contraceptive products and services in many markets. By using appropriate combinations of the marketing mix, social marketing programs ensure different market segments have access to high-quality contraceptive products and services. For example, a social marketing program in Nepal offers a higher-priced oral contraceptive to wealthier urban populations and a lower-priced option to rural populations.6 By marketing high- quality products at affordable prices, social marketing programs can also help reduce the availability, sale, and use of poor-quality products.7 Many social marketing programs contribute to expanding access to a wide range of contraceptives by offering multiple family planning products and services, including male and female condoms, injectable contraceptives, implants, intrauterine devices (IUDs), oral contraceptive pills, and emergency contraceptive pills, at the same service delivery point. The Standard Days Method and mobile applications for fertility awareness and permanent methods are also successfully marketed by social marketing programs across several African countries.8

Lack of availability of contraception products and services in public health facilities. Social marketing helps to ensure that family planning products and services are available to users in ways that expand availability and choice, such as being available at different hours or providing more options. For example, social marketing programs can reach remote villages where distribution by the commercial sector is not financially viable. Additionally, social marketing can tap into additional, often far-reaching networks of commercial and non-governmental health care providers and retail outlets.9 Social marketing programs use market data to understand the characteristics of current and potential private sector clients to find and ultimately meet the needs of underserved populations in ways that government programming often cannot.10

Social marketing was key to building a market for the levonorgestrel IUD, a new product in Madagascar. As a result of a successful product introduction in the private sector, the Ministry of Public Health has decided to work with development partners to introduce and expand access to the hormonal IUD in the public sector. The pilot was designed to test a partial cost recovery model for the levonorgestrel IUD (brand Avibela) in 37 private health clinics. Forty-seven providers were trained and supported to expand the range of contraceptive methods offered at different price points. This allowed providers to set the cost according to the client’s ability to pay. Providers adhered to quality standards in exchange for training, certification, supplies, continuing education, and quality assurance.11,12 In the pilot, nearly 2,500 women chose the hormonal IUD over three years.13

Lack of access to contraception among particular segments of the population. Social marketing can be a good option to provide family planning services to populations not reached through public sector programs. For example, young people are more likely to choose private sector sources to meet their contraceptive needs14 because these sources tend to provide more anonymity and easier availability than public sector sources10 (See HIP Strategic Planning Guide on adolescents and male engagement).

Lack of a wide range of contraceptives in private sector outlets. Social marketing programs can link private facilities to quality-assured products and sensitize providers to offer contraception. For example, the Dimpa program in India helped introduce injectable contraceptives (depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate, or DMPA) in private health facilities, leading to the inclusion of injectables in the national family planning program.15 A social marketing program in Nigeria collaborated closely with private providers and government to increase the availability and provision of IUDs, implants, and oral contraceptive pills in private facilities.16

In Nepal, the Contraceptive Retail Sales (CRS) social marketing program supports pharmacies to offer injectable contraception to their clients. The “Sangini network” includes nearly 3,400 pharmacies across all 75 districts of the country. The social marketing program trains providers, promotes the network via mass media and conducts periodic support visits to ensure quality of family planning provision by Sangini providers. The Sangini network provides approximately 25% of all injectable users nationally.17

What is the evidence of impact?

Social marketing programs can increase knowledge of, demand for, access to, and use of contraceptive products and services. Four notable systematic reviews of social marketing family planning programs found positive impact on clients’ knowledge of, access to, and use of contraceptive methods.18–22 One of the systematic reviews of social marketing broadly found that programs that used “audience insight” and “addressed both the cost and benefits of behavior change” were more likely to be effective. The review concluded that social marketing is effective in changing behavioral factors (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, perceived access) and behaviors (e.g., use of contraceptives) and achieving desired health outcomes (e.g., prevent unintended pregnancies) though the effects related to reproductive health were weaker than other health sectors.21

Social marketing programs particularly serve the needs of short-acting contraceptive users. There is strong evidence that a large proportion of those who use oral contraceptive pills and condoms rely on social marketing. Since 2000, 46 countries have collected Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data on socially marketed products, of which 36 reported that more than 70% of pill users use socially marketed products. Thirty-three countries reported similar data on condom use. Among these countries, 31 report more than 60% of clients use socially marketed brands (ICF, 2021).22 The contribution of social marketing programs in terms of overall contraceptive use has continued to increase steadily, doubling in the last decade.4 In 2017, social marketing programs delivered 80 million couple years of protection4 in more than 80 programs and 60 countries. More specifically, social marketing can specifically adjust the promotion and price of a product to a specific potential user, something that often has a significant impact on the decision to use short-acting contraception like condoms.23

Social marketing programs reach priority populations effectively. While often associated with urban markets, social marketing can also reach rural residents through rural drug shops, mobile outreach, and community-based distribution programs. Young people can be reached through social marketing accompanied by youth-oriented social media campaigns.24,25 To address Ethiopia’s lack of access in rural areas, the country created a social marketing community-based health worker (CHW) program through which CHWs provide family planning counseling; sell and provide short-acting methods to interested clients, including injections; and make referrals for other methods. During the first three years of the program, approximately 600 CHWs provided an estimated 15,410 injections, contributing 3,853 couple-years of protection for 8,604 women, and helping to increase contraceptive use from 30.1% to 37.7%, with injectables largely responsible for this increase.26 In some countries, as a strategy to reach women with limited mobility, youth or other client segments, beauty parlor staff are trained to engage in health conversations with their clients, to sell select family planning products, and/or refer interested women to family planning clinics for additional care.

Social marketing programs contribute to building a healthy market. Social marketing programs that market their own brands and initiatives implemented in partnership with pharmaceutical companies have sustained the increases in contraceptive use even after donor support ended. South Africa and Paraguay transitioned donor-funded condom social marketing programs into financially self-reliant operations.27,28 In Sri Lanka non-governmental organizations reached high levels of financial self-sufficiency through a social enterprise model. Income from social marketing covers more than 80% of the overhead of the Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka, which delivers contraceptives to clients at no cost through its own clinics and sells products at market rates through commercial outlets and service providers.29 In many countries, there are examples of social marketing programs that have been able to transition from being fully donor dependent to increasingly financially sustainable, with 70% of operating costs covered by revenue. This has happened through a mixture of effective marketing, lower contraceptive procurement costs, and overall economic growth.30

In countries with low mCPR countries (mCPR < 20%), “over one-third of pharmacy and drug shop clients are youth.”32 In Nigeria, younger women (<25 years old) who use short-acting methods were significantly more likely to obtain their method from a pharmacy or drug shop than another type of facility.5 Youth cited convenience as a major draw of pharmacies, specifically their longer operating hours, accessible locations, and ease of family planning commodity access.37 In Delhi, a survey of pharmacists providing EC found one-third of the clients were adolescents.38

How to do it: Tips from implementation

Social marketing programs can be used in a variety of settings and should be tailored to the country context and the program’s objectives. A social marketing program may introduce its own brand of a family planning product or choose to partner with a product manufacturer or supplier with a quality-assured brand. Some programs also undertake activities to build a supportive environment for social marketing, including policy and advocacy, partnerships, capacity building, and service delivery.31 The following tips are applicable to a variety of family planning social marketing programs.

Begin with the end in mind. Technical, financial, institutional, and market aspects should be considered from the onset of a social marketing program with the goal of providing consistent, reliable support for clients and creating a market that responds to changing needs, values, and preferences over time.32 Over time, financial reliance on donors and other external resources should decrease as cost recoveryi increasingly supports the cost of products and the program.30 As part of the planning, support the government in its role as steward of the health system and develop a plan for when and how to evolve aspects of the market, including social marketing.

Creating sustained behavior change, not just changing knowledge and attitudes. To ensure this concept is central to social marketing programming, the National Social Marketing Centre in the United Kingdom has identified a set of key principles (Box 1):

- Clearly identify the audience, segmenting and tailoring interventions accordingly

- Seek to understand audience members’ lives, behaviors, motivations, and constraints using relevant theories

- Seek to understand competing behaviors

- Maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of adopting a new behavior to create an attractive exchange

- Use a mix of methods to facilitate behavior change based on the factors influencing the practice

iCost meaning using sales revenues to cover the cost of products and programs, is possible in social marketing through the creation of a price structure that “maximizes revenues without sacrificing the ability of low-income consumers to purchase contraceptives.” 30

Conduct audience research. Review and analysis of data (e.g., DHS, formative research, participatory action research, and human-centered design) helps social marketing programs gain insight into and segment the target audience. In Madagascar, conducting audience research helped the program position the hormonal IUD as a contraceptive product with lifestyle benefits, such as lighter menstrual periods, and clients cited non-contraceptive benefits as among the top three reasons why they chose the method. In addition, continuous monitoring and evaluation using service statistics, sales figures, and other data will help in iterative adjustments to program design and implementation and ensure greatest impact.

Invest in multi-year social and behavior change. Social marketing programs should include both supply and demand-side components, including components to address health care provider barriers. Campaigns and local promotional activities need to be rooted in audience research, continually monitored, and adjusted over time. (See the HIP social and behavior change briefs for more information.)

Support coordination among government, private sector, and social marketing programs. Coordination among different sectors will help ensure that free and heavily subsidized social marketing products are targeted to those who need them the most. All sectors need to share data, communicate regularly, and have a common understanding of the marketplace to ensure that products are available and clients receive uninterrupted services. In many countries, family planning/reproductive health technical working groups (TWGs) made up of representatives of the public sector, donors, implementing partners, and civil society meet to coordinate efforts. These TWGs are a good place to address market issues and could include the commercial sector when discussing market dynamics. Collaboration among sectors is also important in ensuring an enabling policy environment that facilitates a multisector total market approach to family planning.

Where possible leverage existing infrastructure. If there are quality-assured commercial brands already present in the market or manufacturers with capacity and interest in investing in a new market, social marketing programs should collaborate with and support commercial suppliers to build a market for their products.

Ensure subsidized social marketing products are targeted and priced appropriately. When donor-supported programs are not targeted to a specific population segment, social marketing efforts may crowd out commercially viable contraceptives from those individuals who can afford to pay, perpetuating reliance on donor support for sustaining supplies.33 With proper pricing structures and adequate planning, financing, and coordination, the entire population in need can be served with contraceptive products, including free distribution for those in the poorest communities, partially subsidized products for those with slightly greater resources, and commercially distributed unsubsidized products for those with a greater ability to pay.34

Increase cost recovery and support a fair marketplace. Social marketing programs should periodically monitor and keep up with trends in price elasticityii and other market conditions such as inflation and per capita income. By adjusting to the market conditions, social marketing programs can not only increase their cost recovery but also create a marketplace that allows commercial manufacturers to enter the market. Social marketing can and should be implemented to avoid crowding out the for-profit private sector, particularly in countries that are more advanced economically and have higher overall contraceptive prevalence rates.35 However, because an inappropriate price increase may adversely affect poorer populations’ access and use of family planning products, it is important to continually track price elasticity and ability to pay.

Balance branded and generic promotion. Branded promotion is usually necessary to motivate retail outlets to stock the product and for customers to recognize and ask for the product because they perceive value. Many successful social marketing programs benefit from an “umbrella” branding strategy, through which many related products are marketed and sold under a single brand name.36 In Benin, Association Béninoise pour le Marketing Social et la Communication pour la Santé (Beninese Social Marketing and Health Communication Association) socially markets all of its family planning methods (pills, injectables, cycle beads, IUDs and implants) under the single brand name “Laafia” (”happiness, health, and fulfillment”) to increase efficiency and impact of its brand promotion and mass media efforts. Generic promotion, or unbranded campaigns, are best suited for promoting the benefits of family planning; addressing misconceptions about family planning (either specific methods or in general); and delaying, spacing, or limiting future pregnancies per fertility intentions.

iiPrice elasticity of demand is an economic measure of how demand changes when a product’s price increases or decreases.37

- Social Marketing for Health: Global Health eLearning Center. This course provides an overview of social marketing and how it can be applied to improve health. https://globalhealthlearning.org/course/social-marketing-health

- International Social Marketing Association (ISMA). The website provides resources to advance social marketing practice, research, and teaching through collaborative networks of professionals, supporters, and enthusiasts. https://isocialmarketing.org/

- Keystone Design Framework. A collection of best practices and tools to assist the application of social marketing principles and practices to development programming. https://www.psi.org/keystone/

- Total Market Approach (TMA) Compendium. A compendium bringing together tools and resources that can be used to help understand new ways of engaging country counterparts to support TMA efforts. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/tmacompendium

- Phases of Social Marketing. Building the Sustainability of Donor-Supported Programs. Describes strategies to design and support appropriate and sustainable social marketing programs from start-up to graduation. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/sites/default/files/2017-05/Phases%20of%20Social%20Marketing.pdf

Priority Research Questions

Although social marketing is a discipline with proven impact on family planning and other health behaviors, as the field continues to evolve additional research could help practitioners better understand the impact of social marketing and better target their interventions. Evidence on the following questions will contribute to growing the evidence base for social marketing:

- How do social marketing program models evolve over time to sustain or optimize their efficiency?

- How does long-term, sustained use of socially marketed products and services improve overall market growth and access to family planning products and services?

- How does social marketing measurably close equity gaps in contraceptive access?

Indicators to Track Implementation of This High Impact Practice

- Number/percent of pharmacies/drug shops where socially marketed products and/or services are available (disaggregated geographically, product/service)

- Percent of cost recovery of social marketing contraceptive products, disaggregated by product and brand (where relevant)

- Couple Years of Protection (CYP) (https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-areas/family-planning/couple-years-protection-cyp)

References

- International Social Marketing Association (iSMA), European Social Marketing Association (ESMA), Australian Association of Social Marketing (AASM). Consensus Definition of Social Marketing. iSMA; 2013. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.i-socialmarketing.org/assets/social_marketing_definition.pdf

- Khan MT. The concept of ‘marketing mix’ and its elements (a conceptual review paper). Int J Inf Bus Manag. 2014;6(2):95. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1511120790

- Pandit-Rajani T, Bock A, Bwembya M, Banda L. The Next Generation Injectable, A Next Generation Approach: Introducing DMPA-SC Self-Injection Through Private Providers in Zambia. Advancing Partners & Communities Project/USAID DISCOVER-Health Project, JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc.; 2019. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://publications.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=22807&lid=3

- Contraceptive Social Marketing Statistics, 1991–Present. DKT International; 2020. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.dktinternational.org/contraceptive-social-marketing-statistics/

- Khan NA. Marketing a taboo product: tackling the consumer mind-set in Pakistan. Asian J Manag Cases. 2018;15(2):147–60. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0972820118780745

- Increasing access to affordable family planning through a market segmentation strategy. Sustaining Health Outcomes through the Private Sector (SHOPS) Plus, Abt Associates; 2016. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/article/increasing-access-affordable-family-planning-through-market-segmentation-strategy

- Pallin SC, Meekers D, Longfield K, Lupu O. Uganda: A Total Market Approach for Male Condoms. Population Services International; 2013. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Total_Market_Approach_Uganda.pdf

- Kavle J, Eber M, Lundgren R. The potential for social marketing a knowledge-based family planning method. Soc Mark Q. 2012;18(2):152–166. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1524500412450486

- Riley C, Garfinkel D, Thanel K, et al. Getting to FP2020: Harnessing the private sector to increase modern contraceptive access and choice in Ethiopia, Nigeria, and DRC. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192522. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192522

- Pandit-Rajani T, Cisek C, Dunn C, Chanda M, Zulu H. Zambia Total Market Approach (TMA) Landscape Assessment: Contraceptives and Condoms. USAID DISCOVER-Health Project, JSI Research &Training Institute, Inc.; 2017. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.jsi.com/resource/zambia-total-market-approach-tma-landscape-assessment-contraceptives-and-condoms/

- Danna K, Jaworski G, Rahaivondrafahitra B, et al. Introducing the hormonal intrauterine device in Madagascar, Nigeria, and Zambia: results from a pilot study. Research Square. Preprint posted online June 16, 2021. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-606544/v1

- Danna K, Jackson A, Mann C, Harris D. Expanding Effective Contraceptive Options: Lessons Learned From the Introduction of the Levonorgestrel Intrauterine System (LNG-IUS) in Zambia and Madagascar. Expanding Effective Contraceptive Options, WCG Cares; 2020. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/IUSCaseStudy_d7-digital.pdf

- Population Services International (PSI). Expanding Effective Contraceptive Options (EECO) Year 8 Semi-Annual Report. PSI; 2021.

- Weinberger M, Callahan S. 2017. The Private Sector: Key to Reaching Young People with Contraception. Sustaining Health Outcomes through the Private Sector (SHOPS) Plus, Abt Associates; 2017. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/The%20Private%20Sector%20Key%20to%20Reaching%20Young%20People%20with%20Contraception.pdf

- Dalious, M, Ganesan R. Expanding Family Planning Options in India: Lessons From the Dimpa Program. Strengthening Health Outcomes through the Private Sector (SHOPS) Plus, Abt Associates; 2015. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/Expanding_Family_Planning_Options_in_India-Lessons_from_the_Dimpa_Program.pdf

- Society for Family Health, Expanding Social Marketing Program in Nigeria (ESMPIN). Technical Briefs. ESMPIN; 2017. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ESMPIN__Technical_Briefs_FINAL_LR2.pdf

- Smith B, Brunner B, Bhattarai S. Assessment of the Ghar Ghar Maa Swaasthya (GGMS) Project. Sustaining Health Outcomes through the Private Sector (SHOPS) Plus, Abt Associates; 2019. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/GGMSAssessment_Final_Web11.25.2020%20sxf%2012-02-20.pdf

- Chapman S, Astatke H. Review of DFID Approach to Social Marketing. Annex 5: Effectiveness, Efficiency and Equity of Social Marketing, Appendix to Annex 5: The Social Marketing Evidence Base. DFID Health Systems Resource Centre; 2003. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08d1a40f0b652dd001774/Review-of-DFID-approach-to-Social-Marketing-Annex5.pdf

- Madhavan S, Bishai D. Private Sector Engagement in Sexual And Reproductive Health and Maternal and Neonatal Health: A Review of the Evidence. DFID Human Development Resource Centre; 2010. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/330940/Private-Sector-Engagement-in-SRH-MNH.pdf

- Sweat MD, Denison J, Kennedy C, Tedrow V, O’Reilly K. Effects of condom social marketing on condom use in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 1990-2010. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(8):613–622A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.11.094268

- Firestone R, Rowe CJ, Modi SN, Sievers D. The effectiveness of social marketing in global health: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(1):110–124. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw088

- ICF. The DHS Program STATcompiler. Funded by USAID. ICF. Accessed June 29 2021. http://www.statcompiler.com

- Terris-Prestholt F, Windmeijer F. How to sell a condom? The impact of demand creation tools on male and female condom sales in resource limited settings. J Health Econ. 2016;48:107–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.04.001

- Pfeiffer C, Kleeb M, Mbelwa A, Ahorlu C. The use of social media among adolescents in Dar es Salaam and Mtwara, Tanzania. Reprod Health Matters. 2014;22(43):178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(14)43756-X

- Merrick TW. Making the Case for Investing in Adolescent Reproductive Health: A Review of Evidence and PopPov Research Contribution. Population and Poverty Research Network/Population Reference Bureau; 2015. https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/poppov-report-adolescent-srh.pdf

- Weidert K, Gessessew A, Bell S, Godefay H, Prata N. Community health workers as social marketers of injectable contraceptives: a case study from Ethiopia. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(1):44–56. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00344

- Garçon S. Are you in the market for condoms? February 14, 2017. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.psi.org/2017/02/are-you-in-the-market-for-condoms/

- Population Services International (PSI). From Innovation to Scale: Advancing the Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Young People: A Review of Population Services International Programming Approaches and Experiences. PSI; 2016. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Youth-SRHR_Dec2016.pdf

- International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF). Maximizing Social Enterprise: Creating Financial Value to Improve Lives. IPPF; 2016. https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/2016-06/IPPF%20Social%20Enterprise%20Capability%20Statement%20Jun16.pdf

- Purdy C. How one social marketing organization is transitioning from charity to social enterprise. Soc Mark Q. 2020;26(2):71–79. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1524500420918703

- Sustaining Health Outcomes through the Private Sector (SHOPS) Plus. Advocating for Social Marketing Programs to Local Stakeholders. SHOPS Plus, Abt Associates; 2017. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/Advocating_for%20Social%20Marketing%20Programs%20to%20Local%20Stakeholders.pdf

- O’Sullivan G, Cisek, C, Barnes J, Netzer S. Moving Toward Sustainability: Transition Strategies for Social Marketing Programs. Private Sector Partnerships-One, Abt Associates; 2007. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://banyanglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Moving-Toward-Sustainability-Transition-Strategies-for-Social-Marketing-Programs.pdf

- Longfield K, Ayers J, Htat HW, Neukom J, Lupu O, Walker D. The role of social marketing organizations in strengthening the commercial sector: case studies for male condoms in Myanmar and VietNam. Cases in Public Health Communication & Marketing. 2014;8(Suppl 1):S42–S63. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CasesVol8SupplLongfield_Final.pdf

- Htat HW, Longfield K, Mundy G, Win Z, Montagu D. A total market approach for condoms in Myanmar: the need for the private, public and socially marketed sectors to work together for a sustainable condom market for HIV prevention. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i14-i22. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czu056

- Taruberekera N, Chatora K, Leuschner S, et al. Strategic donor investments for strengthening condom markets: the case of Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0221581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221581

- Erdem T. An empirical analysis of umbrella branding. J Mark Res. 1998;35(3):339–351. https://doi.org/10.2307/3152032

- Korachais C, Macouillard E, Meessen B. How user fees influence contraception in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Stud Fam Plann. 2016;47(4):341–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12005

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Social Marketing: Using marketing principles and techniques to improve contraceptive access, choice, and use. Washington, DC: HIP Partnership; September 2021. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/social-marketing

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by: Roselline Achola (UNFPA), Norbert De Anda (PSI), Ramakrishnan Ganesan (Abt Associates), Laura Hoemeke, Shawn Malarcher (USAID), Elaine Menotti (USAID), Rachel Mutuku (PSI), Gael O’Sullivan (Georgetown University), Tanvi Pandit-Rajani(JSI), Christina Wakefield (The Manoff Group), and Jane Wickstrom. It was updated from a previous version, available here.

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Clancy Broxton (USAID), Maria Carrasco (USAID), Mirriam Chege (AMREF Health Africa), Ashley Jackson (PSI), Muka Chikuba-McLeod (JSI), Alam Dawood (EngenderHealth), Kamden Hoffman (CORUS International), Kuyosh Kadirov (USAID), and Joan Kraft (USAID).

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

To engage with the HIPs please go to: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/engage-with-the-hips/

To provide comments on this brief, please fill out the form on the Community Feedback page.