Galvanizing Commitment: Creating a supportive environment for family planning programs

Background

Demonstrable commitment to family planning strengthens the enabling environment in which programs and policies are implemented. Countries such as Indonesia, Mexico, and Turkey have longstanding commitments to family planning, as demonstrated by their use of domestic resources, work toward strengthening systems at subnational levels, and increases in contraceptive prevalence rates (Alkenbrack & Shepherd, 2005; Ozvaris et al., 2004; Seltzer, 2002). Regardless of past performance, countries can experience stagnation as their commitment to family planning lags over time (Putjuk, 2014).

Regional and international initiatives, such as the 2011 Regional Conference on Population, Development and Family Planning and the subsequent creation of the Ouagadougou Partnership as well as the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning and the establishment of Family Planning 2020 (FP2020), have reenergized the family planning community. As a result, countries and their development partners have recommitted to meeting the reproductive needs of their constituents. Sustained advocacy and accountability mechanisms are needed to ensure these commitments come to fruition.

This brief examines the process of commitment making, highlighting three forms of commitment — expressed, institutional, and financial — at the global, regional, country, and subnational levels. The commitment process begins by defining the underlying issues or problems that need to be addressed to improve access to and quality of family planning information and services. Evidence about the extent of the problem is useful for identifying the type of commitment that is needed to improve the situation. Advocacy plays a key role in moving toward establishing commitment as stakeholders link the problem and evidence with the specific investment needed. Once made, stakeholders monitor implementation of the commitment to ensure that it leads to improvements in the underlying issue.

Commitments can result in hollow promises. Accountability—applying pressure to leaders to follow through on their promises—plays a parallel role to commitment. Through accountability efforts, a diverse range of stakeholders exert civil and moral authority to ensure commitments are upheld and resources are used efficiently, effectively, and equitably.

This brief considers why galvanizing support for family planning is important, presents examples of different types of commitment and how they advance the enabling environment, and offers experiential learning from experts in the field.

Galvanizing commitment is one of several High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs) identified by a technical advisory group of international experts. When scaled up and institutionalized, HIPs will maximize investments in a comprehensive family planning strategy (HIPs, 2015). For more information about other HIPs, see http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/overview.

What is the impact?

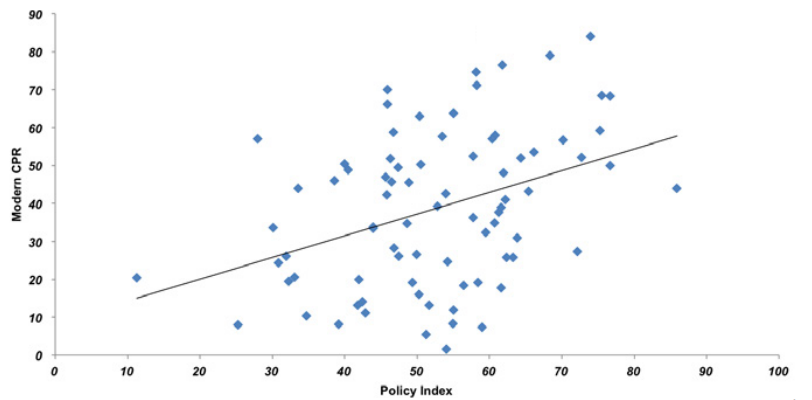

The presence of different types of commitments is tied to a strong policy environment for family planning, which, in turn, is associated with a higher modern contraceptive prevalence rate (mCPR), as illustrated by evidence from the most recent round of the Family Planning Effort Score (FPES). The FPES captures different aspects of national program inputs based on expert observers’ judgments on 30 program features, which are converted to scores in four program effort areas: policy, services, evaluation, and method availability. Figure 1 shows the relationship between the strength of the policy environment for family planning as assessed in the FPES and the country’s mCPR. While the experience of the 90 countries included in the 2015 FPES shows broad distribution, the overall trend indicates a correlation between a strong policy environment and higher mCPR (Kuang et al, 2015).

Expressed commitment from governments and private-sector leaders can be in the form of a constitutional amendment, law, or policy that guarantees access to health and family planning; development of family planning strategies and costed implementation plans; or incorporation of family planning in national development plans, such as poverty reduction strategies and vision statements. From the private sector, commitments can include policies and programs that support employees’ access to family planning.

Expressed commitments are often the first step toward more substantial ownership and investment in family planning programming. A recent case study on family planning commitments in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda reinforces the importance of expressed commitment and highlights the fact that those commitments can come from different levels of political leadership. In Rwanda, explicit leadership for family planning has come from the president and has cascaded down through virtually all levels of government. In Ethiopia and Malawi, the Ministry of Health (MOH) is the lead spokesperson in support of family planning, coupled with strong communication efforts on birth spacing and land availability for agriculture (Murunga et al., 2012).

The following examples illustrate how expressed commitment can lead to additional commitments and desired outcomes.

- In 2005, the effects of rapid population growth on development and poverty were presented to the Rwandan cabinet using the “Resources for the Awareness of Population Impacts on Development” (RAPID) model projections. (RAPID projects the social and economic consequences of high fertility and rapid population growth for such sectors as labor, education, health, urbanization, and agriculture [Health Policy Initiative, 2009].) By 2006, the MOH had produced a National Family Planning Policy and fiveyear strategy (2006–2010), and the government had included a budget line item for contraceptives (Solo, 2008). Use of modern contraceptives among married women increased dramatically in the intervening years—from 10% in 2005 to 45% in 2010 (INSR, 2006; NISR, 2012). Funding for contraceptives showed a commensurate increase, too: from US$491,231 in 2004 to $5,742,112 in 2008—with the MOH beginning to use its own funds for contraceptive procurement in 2008 (MOH [Rwanda], 2009).

- At the 2011 International Conference on Family Planning in Dakar, Senegal’s President Abdoulaye Wade stated his commitment to family planning, which was renewed at the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning. As a result of his expressed commitment, the MOH is employing more staff to provide family planning services, expanding method mix to better meet clients’ needs, and fostering an environment to expand the role of the private sector (Stratton, 2015). Since 2010, Senegal has experienced a rapid increase in modern contraceptive use, from 10% in 2010–11 to 20% in 2014 (ANSD [Senegal], 2014; UN, Population Division, 2011).

Institutional commitments involve greater investment than an expressed commitment. Examples of institutional commitments include creating or upgrading a public agency (such as a national Population Council) or a permanent standing committee (such as a Family Planning Technical Working Group or Contraceptive Security Committee). The following examples illustrate different forms of institutional commitment that contribute to a more favorable enabling environment for family planning.

- India’s Jharkhand State recognized the need for an institution to address the state’s high fertility rates. It first established the Family Planning Task Force, which was charged to assess services and training needs. The Task Force created a state family planning strategy and created a family planning cell within the State Reproductive and Child Health Office to serve as a sustainable institution to promote family planning in the state (Chokshi et al., 2014).

- Kenya’s National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) is charged with providing leadership and mobilizing support for population programs, as well as creating public awareness on population and development issues. As Kenya’s process of devolution moves forward, the NCPD is collaborating with stakeholders to support advocacy efforts for line items for family planning in county budgets (Health Policy Project, 2015).

Financial commitments reflect a willingness of governments and the private sector to invest resources to advance access to family planning information, services, and commodities. National and subnational governments are increasingly creating budget line items for family planning and, through domestic resource mobilization, are contributing to the sustainability of family planning programs. These line items are an important demonstration of financial commitment; however, funds dispersed for family planning efforts represent a more concrete measure of commitment (Fox et al., 2011). Accountability efforts by donors, governments, and civil society play a vital role in ensuring that financial commitments are honored. The following examples illustrate the extent to which countries are increasing financial commitments to family planning—at both the central and the decentralized level.

- Bolivia’s maternal and infant health insurance program (Seguro Universal Materno Infantil, or SUMI) was expanded in 1999 to include reproductive health and family planning services (Beith et al., 2006). However, because contraceptives were still donated centrally, municipalities were not reimbursed for providing these services. In anticipation of donor phase-out, advocates lobbied to expand SUMI to include reproductive health supplies. As a result, in 2006, SUMI was expanded to cover all its beneficiaries’ reproductive health needs, including contraceptives (USAID | DELIVER PROJECT, 2012).

- Guatemala provides financial support for reproductive health programs through an alcohol tax. As part of the 2010 Healthy Motherhood Law, 15% of the alcohol tax revenue is required to be allotted to reproductive health programming, of which 30% must be used to purchase contraceptive commodities. A budget tracking exercise indicates that moneys have been allocated and disbursed as mandated from the Ministry of Finance (MOF) to the MOH. Between 2006 and 2012, the tax contributed an estimated $24.3 million to reproductive health programming (Reyes et al., 2013).

- Malawian parliamentarians committed to create a new budget line for family planning commodities in 2012. In the 2013/14 budget year, the MOF allocated approximately $80,000 for the budget line (Health Policy Project, 2013). In subsequent years, the MOF increased the allocation to $165,000 and then to $190,000. These increases are largely attributed to the engagement of the parliamentarians in oversight and negotiation with the MOF (personal communication with Patrick Mugirwa, Programme Officer, Partners in Population and Development African Regional Office, June 4, 2015).

- Leaders from 364 Indonesian villages began committing funds to family planning, which are expected to cover data recording and reporting, community mobilization, and transportation costs for users of clinical methods who must travel to access services (AFP, 2015).

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria provides resources for purchasing contraceptives, yet relatively few countries have used this alternative mechanism for contraceptive procurement. Rwanda is among the few that included contraceptives in its Round 7 application, taking advantage of this unique opportunity to galvanize additional financial support for family planning (USAID | DELIVER PROJECT, [2008]).

Civil society and the private sector can also make financial commitments to family planning, reinforcing the idea that reproductive health goes beyond the responsibility of governments. The following examples illustrate commitments made by the private sector to increase use of family planning.

- Merck for Mothers is a 10-year, $500 million private-sector initiative to reduce preventable maternal deaths globally. In Senegal, Merck for Mothers is supporting the expansion of a supply chain innovation to ensure that health facilities maintain adequate stocks of a range of contraceptive options by working with private suppliers (Merck for Mothers, [2013]).

- The Levi Strauss Foundation has created an Improving Worker Well-Being Innovation Fund in which suppliers can co-fund grants to community-based NGOs to help factory owners meet their workers’ health and well-being goals, including sexual and reproductive health.

- Lotus High Tech/Lotus High Fashion is an apparel manufacturing company with more than 8,000 workers located in Port Said, Egypt. After receiving technical assistance from a number of international NGOs, the company implemented structural changes to the on-site health clinic, including expanding the role of nurses, integrating management and clinical functions, and defining clinical quality standards.

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

Advocacy, evidence, and accountability are three interrelated components needed to affirm commitment to family planning programs. Because commitments to family planning can waver in both the public and the private sectors, it is important to invest in systems and processes that support family planning over the long term while strengthening capacity in advocacy and accountability—especially for those times when commitments waver.

- Timing is everything. There are key moments in the political process at which advocacy plays a key role. Family planning advocates must engage early in strategy development so that decision-makers understand the contribution that family planning makes to the development agenda. As governments develop their budgets and expenditure frameworks, it is critical to mobilize advocacy efforts at the right moment in the annual cycle to influence the process. Entering the process too late will not lead to successful results.

- Involve civil society organizations, professional associations, and the media in advocacy. While civil society and professional associations often play a vital role in advocacy, an informed media is also important—not as advocates but as unbiased communicators of the underlying problems, their consequences to the public, and the need for commitments to address the situation.

- Coordinate advocacy efforts. Whether as part of a reproductive health technical working group, contraceptive security committee, or other coordinating board, fostering communication among all sectors helps build trust and confidence.

- Support policy champions. Policy champions are central to reaching decision-makers to plant and nurture ideas of commitment and to follow through with accountability approaches. Cultivate and support champions wherever possible—within different parts of government, the private sector, and academia, as well as within individuals whose work focuses on maternal and child health, HIV, or other health issues. Selecting opinion leaders as champions can be an effective way to achieve advocacy goals, but the champions need to understand what they are being asked to do and may need support to carry out the advocacy effort (FHI 360, 2010).

- Support collection and analysis of financial data. Financial data help decision-makers understand how funds flow between national and international accounts and out-of-pocket expenditures, while also providing information that can be used to hold governments and partners accountable for following through on commitments. Support the collection and use of information on cost, cost-effectiveness, and cost savings, including National Health Accounts and reproductive health subaccounts. The Public Expenditure Tracking Survey (PETS), supported by the World Bank, is another example of a tracking system, which documents use and abuse of public money and provides insights into cost efficiency, decentralization, and accountability.

- Estimate the true resource needs of family planning programs beyond the cost of supplies and equipment. Costed implementation plans should address all aspect of family planning and be realistic in estimating activity costs, as well as the total cost of the plan.

- Ensure program impacts are measured and evaluated. With this evidence, advocates can confirm that resources are used efficiently, effectively, and equitably.

- Use UNFPA’s Global Programme to Enhance Reproductive Health Commodity Security (GPRHCS or UNFPA Supplies) annual report to monitor program performance. This report includes information for 46 countries on financial and expressed commitment for making contraceptive supplies available; existence of rights-based and youth-focused policies for access to family planning being implemented through costed plans along with guidelines and tools; effective national coordinating mechanisms for reproductive health supplies; and national institutions integrating family planning supply chain and procurement issues into training curricula.

- Foster accountability monitoring through FP2020. The annual FP2020 report includes key indicators of country progress toward commitments. Track20 and the Performance Monitoring and Accountability (PMA2020) projects also track key measures at the country level (FP2020, 2015).

- Use social accountability to apply pressure to follow through on commitments. Civil society can play a crucial role in holding governments accountable. Social accountability offers a variety of approaches—from periodic community assessments to ongoing budget tracking. Civil society organizations can work together to identify the most effective approach for tracking the commitment they are monitoring. In addition, they can learn from other coalitions about how to carry out these approaches most effectively (Hecht et al., 2014).

Accelerating Progress in Family Planning: Options for Strengthening Civil Society-Led Monitoring and Accountability identifies options to support stronger monitoring and accountability, particularly social accountability, around family planning. Available from: http://r4d.org/knowledge-center/accelerating-progressfamily-planning-options-strengthening-civil-society-led-monit

Costed Implementation Plan Resource Kit features tools for developing and executing a robust, actionable, and resourced family planning strategy. Available from: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/microsite/cip

Eleven-Step Guide to Ensuring Public-Sector Contraceptive Financing and Expenditure sets out practical steps for policy makers, civil society, and other stakeholders to ensure sufficient funds exist and are spent effectively to ensure reproductive health commodity security. Available from: http://pai.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/11-Step-Guide.pdf

Stewardship for FP2020 Goals: MOH Role in Improving FP Policy Implementation identifies three ways for ministries of health to address barriers to policy implementation and strengthen their role as stewards of national FP2020 efforts. Available from: http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/index.cfm?ID=publications&get=pubID&pubID=347

A review of existing monitoring and accountability initiatives in family planning informed the development of a framework for identifying and designing results-oriented, civil society-led monitoring and accountability efforts for family planning. The framework is structured around three key questions: bottlenecks, actions, and modalities (see the matrix below).

Social accountability can be targeted by the main type of bottleneck: policy and program design and financing; program execution including flow of resources and service delivery; or the rights and satisfaction of family planning clients. These issues occur at the national, subnational, and/or facility and community level. The main approaches for family planning social accountability include tracking expenditures and resources, monitoring service provision (quantity, quality, and appropriateness), empowering citizens and communities, and advocacy. Support may entail improving an organization’s ability to conduct policy analysis, data collection and assessment, and advocacy and communications. Capacity building efforts can be supported within or across several countries by using a joint learning approach as well as through mentoring. Documenting innovations and sharing best practices are potentially key activities in generating new and relevant knowledge about social accountability for family planning, coupled with rigorous evaluations of country experiences (Hecht et al., 2014).

A Framework for Designing Family Planning Monitoring and Accountability Options

| What needs improving? | Family Planning Issue or Bottleneck | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policies, regulations, and budgets | Implementation of policy and regulations | Resource flows | Quality and respect for rights | User experience–appropriateness and satisfaction | |

| Focus Level | |||||

| National | Subnational | Facility | Community or household | ||

| What actions are needed? | Social Accountability Approach | ||||

| Evidence-based advocacy | Resource tracking | Monitoring service provision | Empowerment | Community/provider engagement | |

| What modalities of support? | Capacity Building Area | ||||

| Policy and budget analysis | Data collection | Data analysis | Advocacy | Community engagement | |

| Capacity Building Model | |||||

| Technical training and mentoring | Intra-country joint learning | Inter-country learning and mentoring | Joint implementation | ||

| Documentation and Learning Component | |||||

| Support to experimentation, learning, and evaluation | Documentation and dissemination (Social Accountability Atlas) | Cross-country case studies and analyses | |||

Source: Hecht et al., 2014

For more information about High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs), please contact the HIP team.

References

Advance Family Planning (AFP) [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Bill & Melinda Gates Institute for Population and Reproductive Health; c2015. 364 more Indonesian villages commit to funding family planning; 2015 Apr 28 [cited 2015 Sep 28]. Available from: http://advancefamilyplanning.org/news/364-more-indonesian-villages-commit-funding-family-planning

Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD) [Sénégal]; ICF International. Sénégal: enquête démographique et de santé continue (EDS-continue 2012-2013). Calverton (MD): ICF International; 2014. Co-published by ANSD. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR288/FR288.pdf

Alkenbrack S, Shepherd C. Lessons learned from phaseout of donor support in a national family planning program: the case of Mexico. Washington (DC): POLICY Project; 2005. Available from: http://www.policyproject.com/pubs/generalreport/Mexico_Phaseout_of_FP_Donor_Suppot_Report.pdf

Beith A, Quesada N, Abramson W, Sánchez A, Olson N. Decentralizing and integrating contraceptive logistics systems in Latin America and the Caribbean, with lessons learned from Asia and Africa. Arlington (VA): USAID | DELIVER PROJECT; 2006. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadm542.pdf

Chokshi H, Mishra R, Sethi H, Jorgensen A. Health system strengthening and effective management for Jharkhand family planning. Washington (DC): Futures Group, Health Policy Project; 2014. Available from: http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/index.cfmid=publications&get=pubID&pubId=225

Family Planning 2020 (FP2020) [Internet]. Washington (DC): United Nations Foundation; c2015. Commitments; [cited 2015 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/commitments?commitment_type_id[]=160

FHI 360. Engaging innovative advocates as public health champions. Research Triangle Park (NC): FHI 360; 2010. Available from: http://www.fhi360.org/resource/engaging-innovative-advocates-public-health-champions

Fox A, Goldberg A, Gore R, Barnighausen T. Conceptual and methodological challenges to measuring political commitment to respond to HIV. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14 Suppl 2:S5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3194164/

Health Policy Initiative, Task Order 1. The RAPID model: an evidence-based advocacy tool to help renew commitment to family planning programs. Washington (DC): Futures Group; 2009. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnadq972.pdf

Health Policy Project [Internet]. Washington (DC): Futures Group; c2011. ImpactNow launched in Kenya; 2015 May 14 [cited 2015 Jun 2]. Available from: http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/index.cfm?id=ImpactNowNews

Health Policy Project [Internet]. Washington (DC): Futures Group; c2011. Malawi parliamentarians secure first national funding for family planning commodities; 2013 Jul 11 [cited 2015 Jun 2]. Available from: http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/index.cfmid=MalawiFPCommodities

Hecht R, Poirrier C, Roland M, Tolmie C. Accelerating progress in family planning: options for strengthening civil society-led monitoring and accountability. Washington (DC): Results for Development; 2014. Available from: http://r4d.org/knowledge-center/accelerating-progress-family-planning-options-strengthening-civil-society-led-monit

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). High impact practices in family planning list. Washington (DC): US Agency for International Development; 2015. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/high-impact-practices-in-family-planning-list

Institut National de la Statistique du Rwanda (INSR); ORC Macro. Rwanda demographic and health survey 2005. Calverton (MD): ORC Macro; 2006. Co-published by INSR. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR183/FR183.pdf

Kuang B, Smith E, Brodsky I. Family planning effort index: a global perspective on family planning program effort. Washington (DC): Futures Group, Health Policy Project; 2015.

Merck for Mothers. Senegal [fact sheet]. Kenilworth (NJ): Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; [2013]. Available from: http://www.merckformothers.com/docs/Senegal_fact_sheet.pdf

Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda]. Annual report 2008. Kigali (Rwanda): MOH; 2009. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/MOH-Reports/Final-MoH-annual-report-2008.pdf

Murunga V, Musila NR, Oronje RN, Zulu EM. Africa on the move! The role of political will and commitment in improving access to family planning in Africa. Washington (DC): Woodrow Wilson Center; 2012. Available from: http://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/AFIDEP.pdf

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda]; Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda]; and ICF International. Rwanda demographic and health survey 2010. Calverton (MD): ICF International; 2012. Co-published by NISR and MOH. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR259/FR259.pdf

Putjuk HF. Indonesia’s family planning program: from stagnation to revitalization. DevEx [Internet]. 2014 Sep 25 [cited 2015 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.devex.com/news/indonesia-s-family-planning-program-from-stagnation-to-revitalization-84387

Reyes H, Cruz M, Marin M. Tracking the innovative use of alcohol taxes to support family planning: Guatemala. Washington (DC): Futures Group, Health Policy Project; 2013. Available from: http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/257_GuatemalaEvaluationReportFINAL.pdf

Rw SB, Akin L, Akin A. The role and influence of stakeholders and donors on reproductive health services in Turkey: a critical review. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12(24):116-127. Available from: http://www.huksam.hacettepe.edu.tr/English/Files/SBO_article.pdf

Seltzer JR. The origins and evolution of family planning programs in developing countries. Santa Monica (CA): RAND; 2002. Available from: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monograph_reports/2007/MR1276.pdf

Solo J. Family planning in Rwanda: how a taboo became priority number one. Chapel Hill (NC): IntraHealth International; 2008. Available from: http://www.intrahealth.org/page/family-planning-in-rwanda-how-a-taboo-topic-became-priority-number-one

Stratton S. Senegal celebrates great progress in family planning during national review. Vital [Internet]. 2015 Feb 24 [cited 2015 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.intrahealth.org/blog/senegal-celebrates-great-progress-family-planning-during-national-review#.VQBxemd0x3w

United Nations (UN), Population Division. World contraceptive use 2011. New York: UN; 2011. Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/contraceptive2011/wallchart_front.pdf

USAID | DELIVER PROJECT. Contraceptive security and decentralization: lessons on improving reproductive health commodity security in a decentralized setting. Arlington (VA): USAID | DELIVER PROJECT; 2012. Available from: https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/csdece_lessimpr_0.pdf

USAID | DELIVER PROJECT. Global Fund in Rwanda agrees to finance contraceptives. Arlington (VA): USAID | DELIVER PROJECT; [2008]. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADN674.pdf

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Galvanizing commitment: creating a supportive environment for family planning. Washington (DC): USAID; 2015. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/galvanizing-commitment

Acknowledgements

This document was originally drafted by Jay Gribble, Maria Colopy, Nadia Olson, Tanvi Pandit-Rajani, and Shawn Malarcher. Critical review and helpful comments were provided by Gifty Addico, Moazzam Ali, Michal Avni, Smita Baruah, Meghan Bishop, Bettina Brunner, Linda Cahaelen, Ellen Eiseman, Sarah Fox, Mary Lyn Gaffield, Babacar Gueye, Rachael Hampshire, Roy Jacobstein, Benedict Light, Erin Mielke, Gael O’Sullivan, Julio Pacca, Leslie Patykewich, May Post, Michelle Prosser, Suzanne Reier, Elaine Rossi, Shelley Synder, Sara Stratton, Stan Terrell, Caitlin Thistle, and Caroll Vasquez.

This HIP brief is endorsed by: Abt Associates, Care, Chemonics International, EngenderHealth, FHI 360, Georgetown University/ Institute for Reproductive Health, International Planned Parenthood Federation, IntraHealth International, Jhpiego, John Snow, Inc., Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Management Sciences for Health, Marie Stopes International, Palladium, PATH, Pathfinder International, Population Council, Population Reference Bureau, Population Services International, University Research Co., LLC, United Nations Population Fund, and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

The World Health Organization/Department of Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/.

For more information about HIPs, please contact the HIP team at [email protected].