Leading and Managing: for rights-based family planning programs

Background

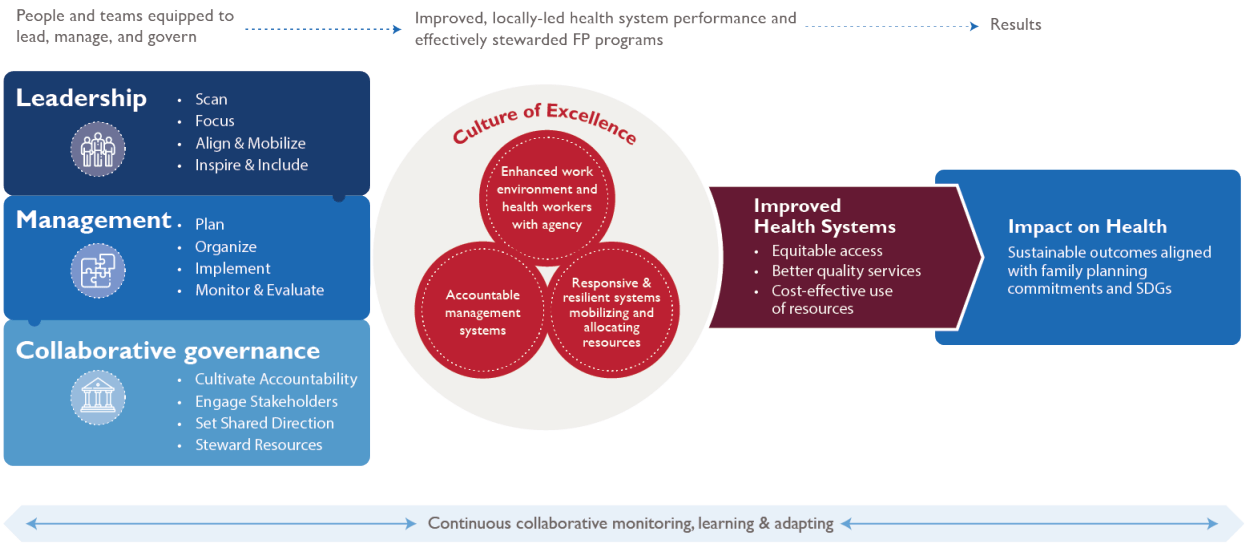

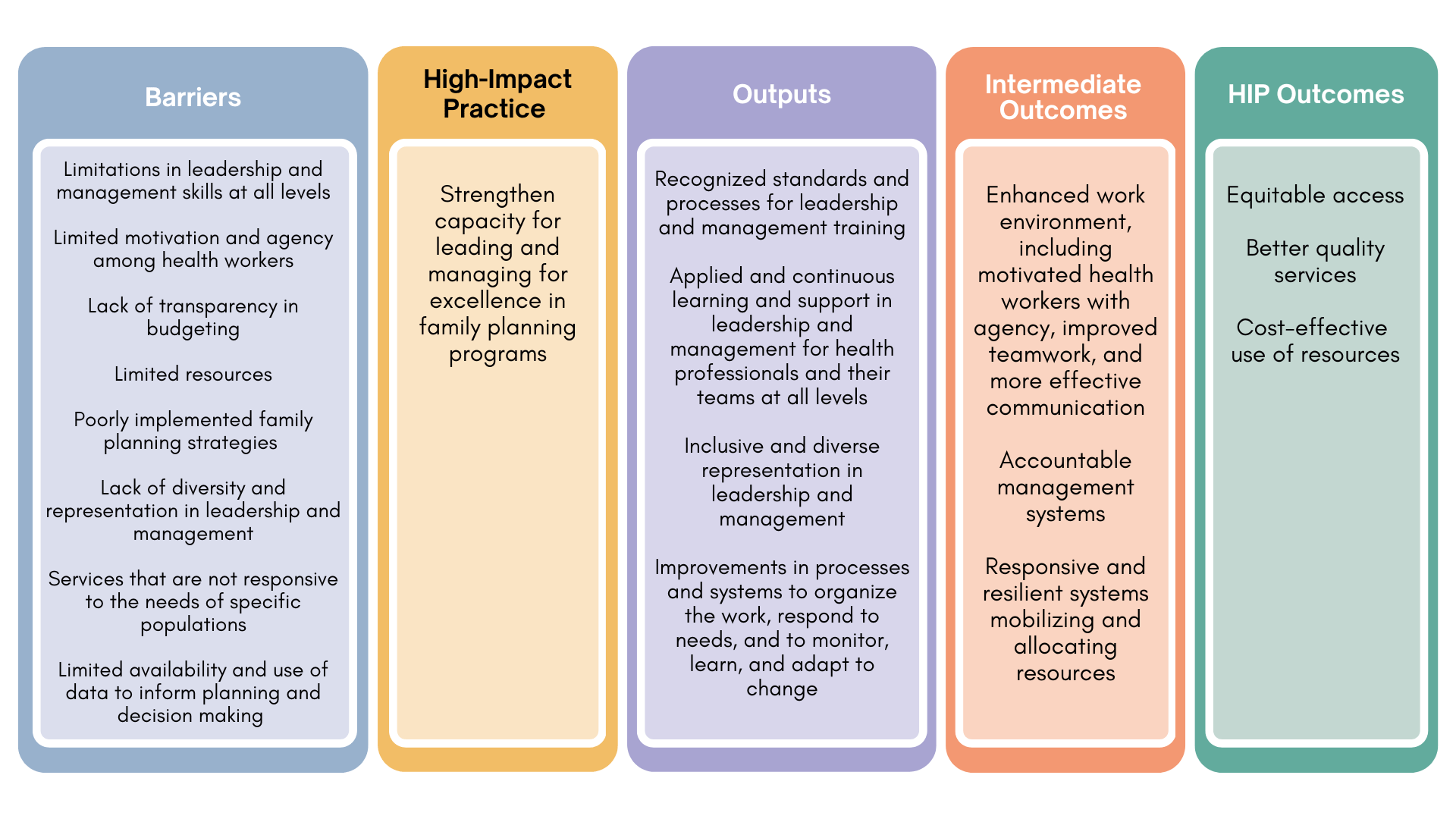

Leadership and management are essential elements for successful, rights-based family planning programs and can help ensure resources are used effectively to achieve results.1–4 Strong leadership and management create a culture of excellence and improved health system performance, ultimately contributing to improved health outcomes (Figure 1).1,5–8 Reports from a study conducted in semi- urban areas of East Africa, Francophone West Africa, India, and Nigeria among participants across tiers of local health governance showed that themes related to leadership and management issues were perceived as “essential elements for scaling up locally-driven family planning programs.”9

Since there are no universally accepted definitions of leadership and management, it is helpful to think about the behaviors and practices that comprise effective leadership and management (Table 1). Strengthening capacity for leading and managing involves improving the ability of individuals to effectively engage in these practices. While this brief focuses on leadership and management, collaborative governance is an important complement to these functions and so it is included in the model to provide a more comprehensive picture. The Enabling Environment Overview HIP brief describes collaborative governance as how different stakeholders work together in consensus-oriented decision making that advances voluntary family planning issues. Collaborative governance broadly is beyond the scope of this brief, but leaders and managers can contribute to good governance by applying the governing practices that are within their sphere of influence.

Practices for Effective Leadership and Management

| Leadership | Management |

|---|---|

|

|

While each function encompasses a unique set of characteristics, leadership and management are most effective when practiced together and leaders and managers must work in tandem to effect positive change.11 Good leaders with strong vision can be poor managers who are unable to motivate and retain staff to achieve goals. Similarly, a good manager who understands staffing, logistics, and financing can lack the skills to create a shared vision and effectively engage their teams to overcome challenges to achieve desired results.

Strengthening leadership and management practices applies to all staff at all levels of the health system from the health facility to supply chain management (see Supply Chain Management HIP brief), and from district to global levels. This attention to multiple levels is even more crucial as decentralization has become a key component of health reform in many countries and has led to the lower levels of the health system holding increasing authority over health budgets and services.12 Good leadership and management practices address diversity, equity, and inclusion by being intentionally inclusive and addressing inequities, for example around gender,13 race, and age, to make programs and systems more responsive and effective at reaching the unreached.

This HIP is one of several “high-impact practices” (HIPs) in family planning identified by the HIP partnership and vetted by the HIP Technical Advisory Group.14 Strengthening leadership and management capacity is critical to the performance of other HIPs and family planning programmatic interventions. Attention to leadership and management should therefore be integrated when implementing any of these practices to realize full potential. For more information about other HIPs, see https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/

Why is this practice important?

Improved work environment enhances health worker motivation and agency.* In family planning programs, provider-level barriers to positive health outcomes include a lack of knowledge and skills among providers about contraceptive methods, low health worker motivation to provide family planning, long wait times for clients to receive services, and disrespectful treatment of clients.15 Many of these issues can be addressed with adequate leadership and management practices to help motivate staff and improve the quality of services, such as recognizing the need for additional staff training, supportive supervision of providers, staff recognition, job aids, and improving logistics systems.15-17 Other analyses have demonstrated the importance of management practices such as having clear job descriptions for clinical staff as key to providing quality family planning services. 18,19

Health workers repeatedly report poor leadership and management by their managers or supervisors as a key factor in their lack of motivation, according to a systematic review of health worker motivation.20 Strong hospital or clinical management was reported in 80% of the reviewed studies as an important factor for health worker motivation. Having a strong organizational mission is another motivating factor for health workers,21 which can be achieved with strong leadership and vision. Health facilities in Kenya experienced improvement in services including integration of services for an efficient service delivery through leadership and peer teamwork in the face of scarce resources. Particular examples where staff displayed agency of decision making and worked as a team while courting management support proved effective in achieving shared and collective goals while overcoming structural deficiencies.23 Leadership style is also important to performance at all levels of the health system. A study in Indonesia found that better leadership style is positively correlated with the performance of employees in the Office of Population Control and Family Planning.24

Improved management systems lead to better health care performance. Systems depend on people and so improved management requires people with strengthened capacity in leading and managing. Health care staff, particularly physicians and nurses, are often put into positions to lead and manage health facilities without the skills to do so.25,26 While trained clinically, physicians and nurses often lack skills in human resource distribution, resource allocation, and recruitment, resulting in poorly managed health facilities. In Kenya, over 70% of clinical staff with management responsibility surveyed reported they had either “no preparation” or “very inadequate preparation” for this aspect of their work.27

There is a need for health care professionals to be equipped with leadership and management skills to carry out the “efficient handling of scarce resources in conditions of uncertainty.”28 A family planning and health worker analysis of 10 African countries concluded that leadership and management functions such as the way “health workers are trained, distributed, and supported may be as important as how many health workers are available.”28 A study in Ghana found that good facility management was critical for improving primary health care performance and health outcomes and highlights that improving health outcomes in primary health care will require strengthening management practices.30 Another study in six districts in Ghana found managerial capacity of district health managers was positively associated with district health performance, as assessed with a metric that included family planning acceptor rate.31

Improved capacity for programs to respond to changing community needs and to effectively scale up. The responsive and inclusive leadership and management practices lead to better decision making that takes multiple perspectives into consideration. For example, responsive policies, programs, and services have been linked as a direct outcome of youth participation and leadership in adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health and rights.32 A review of scale-up of health programs identified strong leadership and management as being a critical factor for success.33 While political leadership can help facilitate resources and commitment, leadership and management at the implementation level is equally critical and will ultimately drive the successful scale-up of health interventions.33

Leadership and management training around prioritization, planning, and identifying a shared vision among implementers and the community contributed to successful scale-up of the Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) program in Ghana.34 In Nigeria, health system factors were important in scaling up community-based distribution of injectable contraceptives, enabled by the actions and considerate decision making among frontline health workers.35

*Agency describes “the capacity of individuals to make their own free choices and act independently on them.” 22

What is the impact?

Demonstrating a direct causal impact between strengthening capacity for leading and managing and health service outputs and health outcomes is an ongoing challenge.6 Models can describe the effects of leadership and management practices using intermediate indicators, such as change in work climates, improved organizational management, or improved capacity to mobilize and allocate resources (Figure 1). These changes may then lead to impact described as: 1) more equitable access to services; 2) better quality services; and 3) more efficient and cost-effective use of resources, aligning with USAID’s Vision for Health System Strengthening intermediate outcomes of equity, quality, and resource optimization.36 This in turn is expected to lead to improved, sustainable health outcomes. Table 2 describes evidence from studies that explicitly aimed to strengthen capacity in leadership and management.

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

A range of leadership and management strengthening approaches have been implemented across regions. As an overarching tip, programs aimed to strengthen leadership and management capacity should be designed with sustainability of the intervention in mind, for example by incorporating into pre-service training, creating standards, and using applied learning approaches. While there is no one way to strengthen leadership and management capacity, below are key issues to consider.

Use mentoring and coaching approaches for ongoing support to leaders and managers. Mentorship and coaching are especially important to developing new leaders, and they enhance the learning that comes through other sources and provide ongoing support and inspiration.39,40 Mentorship and coaching have been key components of leadership and management programs that contribute to improvements in family planning related indicators, including the examples

in Cameroon and Ethiopia cited in Table 2. Efforts to improve district health management capacity in Ethiopia found that the most prominent improvement in adherence to management standards occurred during exposure to intensive mentorship and education.41 An innovative online coaching approach has been key to success in improving youth sexual and reproductive health interventions in urban areas in 11 countries in Africa and Asia and has included coaching governments on using data to monitor impact and increasing youth engagement.42

Create standards and certification for leadership and management roles. Standards related to leadership and management competencies are unfortunately rare, and there are no generally accepted standards and pathways to develop the management workforce for the health care profession, including for family planning.44 However, the climate has been changing. For example, the Ministry of Health in Ethiopia piloted a management capacity enhancement model using a hospital management indicator checklist in 2007. This is targeted at improving hospital services through institutionalizing management skills across cadres of health care providers.44,45

Train teams that work together through applied learning and collaborative learning approaches. Applied learning is the most effective way to gain practical skills in leadership and management, yielding skill retention rates of up to 75% compared with 5–10% from only reading or lectures.46 Using applied-learning approaches with teams working together in real workplace settings has more positive results than sending individuals to off-site leadership and management trainings in which the curriculum is not necessarily directly applicable to their work. Experience from Ghana found stand- alone workshops to be an ineffective tool for leadership training.34 In Kenya, long-term leadership training complemented with facility-based team coaching led to significant and sustained improvements in health service delivery indicators compared with minimal change in institutions without the intervention.47 Collaborative learning approaches that support leadership and management practices are critical to ensure health care leaders and managers have the knowledge and skills to help their organizations achieve their objectives.48

Include leadership and management capacity strengthening in pre-service and in-service training. Leadership and management training has been incorporated into medical and nursing school curricula in multiple countries. In Uganda, in addition to receiving clinical training, students are trained on human resources management, finance, logistics, and leadership. A review of lessons from Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Zambia on integration of leadership and management practices into preservice training identified critical success factors, including a needs assessment to identify gaps, prepared faculty, and senior-level staff with awareness of the importance of leadership and management.49 The Zambian Ministry of Health introduced an in-service leadership and management course, and an impact evaluation in 2014 found improvements in knowledge and in the workplace environment.50 In-service training should incorporate virtual/blended learning to increase convenience and lower costs and, as noted above, should be supported by mentoring and coaching approaches to sustain learning.51

Connect leaders and managers to a larger community of practice that shares common goals for family planning.52 Establishing or connecting with a community of practice enables leaders and managers to develop shared resources including experiences, tools, and problem-solving approaches.53 At national, regional, district, subdistrict, or facility levels, communities of practice could be established through mechanisms such as technical working groups, a stakeholder leadership group,54 or through the use of technology to establish communication arenas such as listservs and websites.

Improve leadership and management skills at multiple levels of the health system for greater impact. A study in Ethiopia showed the interaction among different levels in demonstrating “that having stronger management at the woreda [district] health office magnified the positive effects of strong management at the health center level” and that management capacity was associated with better performance particularly in districts with median management capacity. This suggests that investing in district-level leadership and management capacity development is an opportunity for improving health system performance.55 In Senegal, a study showed that “districts can play a leadership role in implementing family planning services and mobilizing some of their own resources and that international projects can facilitate capacity building and sustainability within public-sector systems.”56 In addition, social accountability initiatives can strengthen the capacity of community members and civil society to help hold facilities and decision makers accountable (see Social Accountability HIP brief).

Address inequities and imbalances of power in leadership and management, e.g., along gender, age, and racial lines. Leadership and management training initiatives should make a concerted effort to identify and cultivate more diverse leaders and create specific trainings for marginalized populations. The Empowering Women Leaders program brought together 70 women leaders for an intensive program of mentoring and training for skills development and building of networks for locally driven change, leading to increases in leadership knowledge and skills.13 It is important to cultivate a new generation of leaders, including looking to youth movements and initiatives to identify promising young leaders. Lessons from youth leadership initiatives include the need for intentional recruitment and actively building capabilities.32 There is a growing movement to shift power and decision making in global health, for as Büyüm et al. note, “leadership at global agenda-setting institutions does not reflect the diversity of people these institutions are intended to serve.”57

New leadership and management skills are needed for changing times and to deal with future challenges. Training leaders and managers should go beyond the standard subjects to develop leaders and managers who can drive innovation and are adaptive, resilient, inclusive, and empathetic.58 This requires different approaches and methodologies to deal with complex and changing environments in which family planning programs operate as well as emotional intelligence in leadership.†

†Emotional intelligence is defined as the ability to understand and manage your own emotions, as well as recognize and influence the emotions of those around you.59

Illustrative Results of Selected Leadership and Management Interventions

| Country | Scale of Implementation | Approach | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cameroon(Baba et al, 2016)4 | 6 tertiary hospitals in Cameroon | A quasi-experimental design was used to evaluate the relationship between a leadership, management, and governance capacity-building intervention (Leadership Development Program Plus [LDP+)]) and postpartum family planning service-delivery improvement in tertiary-care hospitals. | Hospital staff trained in leadership and management had statistically significant 4.4 point improvements in inspiring personnel in the leadership domain. In the management domain, there were 4.3, 2.9, and 2.2 point improvements from pre- to post-LDP+ in monitoring and evaluation, organizing behavior responses, and in planning-related behaviors, respectively. LDP+ impacts on services delivery showed improved attitudes, team cohesion, and problem-solving skills among staff. There were statistically significant increases in the proportion of clients who received family planning counseling (0% to 57%) and postnatal care (17% to 80%) when LDP is included in clinical training. |

| Zambia

(Foster et al 2018)37 |

5 nurse supervisors from each of 5 districts and 20 nurse facility heads across 20 rural facilities spread within the 5 districts | Leadership and management learning program offered to district and rural facility heads for 12 months. Program focused on increasing their ability to lead health care staff and strengthening their technology use ability. |

Nurses and nurse-midwives leading low-resource health facilities at the community level improved their capacity to engage community members and increased their ability to lead teams with improved ability to use technology. Results also show optimized investments in the community health system to achieve high-quality services as a result of the learning program. Improvements in clinical service delivery include:

|

| Ethiopia

(Argaw et al., 2021)38 |

Between 2017–2019, 184 districts and 519 health centers had healthcare workers participate in the leadership, management, and governance (LMG) program | Team-based in-service capacity development program with mixed modules, including 6-day instructional sessions and hands-on implementation of performance improvement projects. In addition, there were supplemental 3–4 coaching sessions and participation in knowledge sharing events. The trainees developed and implemented 656 performance improvement projects. |

Results show higher improvement in capacity of health workers, team coherence, and achievement of outputs in the LMG intervention districts compared to non-LMG intervention districts. Exposed primary health care facilities were shown to have better and higher scores in management systems, work climates, and ability to respond to new challenges than non-exposed facilities. The LMG intervention-exposed primary health care facilities also had a 6.84% higher maternal and child health service performance coverage, higher contraceptive acceptance rates, skilled birth attendance, postnatal care, and growth monitoring service coverages compared to nonintervention facilities. |

The following resources provide an illustrative range of materials to help strengthen leadership and management practices of teams working in family planning programs.

- Managers Who Lead: A Handbook for Improving Health Services. Provides managers with practical guidelines and approaches for leading teams to identify and find solutions for their challenges. Staff at any level of the health system can use this to improve their ability to lead and manage well. Available from:

- Leadership Development Program Plus (LDP+): A guide for facilitators. LDP+ is an experiential learning and performance improvement process that empowers people at all levels of an organization to learn leadership, management, and governing practices; face challenges; and achieve measurable results. Available in English, Spanish, French, and Portuguese.

- Reflection and Action to Improve Self-reliance and Effectiveness (RAISE) tool. This tool empowers governments to evaluate the effectiveness of their interventions, identify the elements that require strengthening, and implement course corrections to increase impact and ensure sustainability.

Implementation measurement

It is recommended that programs implementing interventions to strengthen capacity for leading and managing for excellence in family planning programs include the following indicators, adapted and defined for each context.

- Proportion of preservice health professional education curricula that include leadership and management content

- Proportion of persons in leadership positions that have formal training in management in health

- Proportion of organizations/facilities/districts that report performance improvements as a result of strengthening capacity in leadership and management (performance improvements can include changes in work climate, management systems, health service delivery, quality of care, utilization of services, etc.)

- Proportion of organizations/facilities/districts that report performance improvements as a result of strengthening capacity in leadership and management (performance improvements can include changes in work climate, management systems, health service delivery, quality of care, utilization of services, etc.)

- Proportion of facility, district health management teams, or other administrative units that have developed a monitoring plan, including annual work objectives and performance measures related to family planning

- Representation among leadership and management that reflects diversity and equity (adapt based on local contexts, e.g. proportion female, youth, etc.)

Priority Research Questions

- What are the costs and benefits of different approaches to strengthening leadership and management?

- What approaches to strengthening leadership and management lead to sustainable improvements in family planning outcomes?

- How can family planning interventions feasibly and effectively incorporate approaches to strengthen leadership and management capacity?

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Everybody’s Business — Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. WHO; 2007. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43918

- Dieleman M, Harnmeijer JW. Improving Health Worker Performance: In Search of Promising Practices. World Health Organization; 2006. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.kit.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/1174_Improving-health-worker-performance_Dieleman_Harnmeijer.pdf

- Beaglehole R, Dal Poz MR. Public health workforce: challenges and policy issues. HumResour Health. 2003;1(1):4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-1-4

- Baba Djara M, Conlin M, Shukla M. Cameroon PPFP Endline Study Report: The Added Value of Combining a Leadership Development Program with Clinical Training on Postpartum Family Planning Service Delivery. Management Sciences for Health; 2016.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Towards Better Leadership and Management in Health: Report of an International Consultation on Strengthening Leadership and Management in Low-Income Countries, 29 January -1 February, Accra, Ghana. WHO; 2007. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70023

- Peterson EA, Dwyer J, Howze-Shiplett M, Davison C, Wilson K, Noykhovich E. Presence of Leadership and Management in Global Health Programs: Compendium of Case Studies. Center for Global Health, George Washington University; 2011. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://msh.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/leadership_and_management_compendium.pdf

- Galer JB, Vrisendorp S, Ellis A. Managers Who Lead: A Handbook for Improving Health Services. Management Sciences for Health; 2005. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://msh.org/resources/managers-who-lead-a-handbook-for-improving-health-services/

- Management Sciences for Health (MSH). Leadership, Management, and Governance Evidence Compendium. From Intuition to Evidence: Why Leadership, Management, and Governance Matters for Health System Strengthening. MSH; 2017. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1864/LMG_Evidence_Compendium_Introduction_and_Pharm_chapters-508.pdf

- Mwaikambo L, Brittingham S, Ohkubo S, et al. Key factors to facilitate locally driven family planning programming: a qualitative analysis of urban stakeholder perspectives in Africa and Asia. Global Health. 2021;17(1):75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00717-0

- Vriesendorp S. Leading and managing: critical competencies for health systems strengthening. In: Health Systems in Action: An eHandbook for Leaders and Managers. Management Sciences for Health; 2010. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://msh.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/2015_08_msh_leading_managing_critical_competencies.pdf

- Kotter JP. What leaders really do. Harvard Business Review. December 2001. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://hbr.org/2001/12/what-leaders-really-do

- Kolehmainen-Aitken RL. Decentralization’s impact on the health workforce: perspectives of managers, workers and national leaders. Hum Resour Health. 2004;2(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-2-5

- West-Slevin K, Jorgensen A. Women Transforming: Empowering Women Leaders for Country-led Development. Health Policy Project; 2015. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/682_WomensLeadershipBrief.pdf

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Family planning high impact practices list. USAID; 2020. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/high-impact-practices-in-family-planning-list

- Tumlinson K, Speizer IS, Archer LH, Behetsa F. Simulated clients reveal factors that may limit contraceptive use in Kisumu, Kenya. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2013;1(3):407–416. http://dx.doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00075

- Provider-generated barriers to health services access and quality still persist. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2013;1(3):294. http://dx.doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00162

- Smith S, Broughton E, Coly A. Institutionalization of Improvement in 15 HCI-Supported Countries. University Research Co., LLC; 2012.

- Thatte N, Choi Y. Does human resource management improve family planning service quality? Analysis from the Kenya Service Provision Assessment 2010. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(3):356–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czu019

- Bennett S, Gzirishvili D, Kanfer R. An In-Depth Analysis of the Determinants and Consequences of Worker Motivation in Two Hospitals in Tbilisi, Georgia. Major Applied Research 5, Working Paper 9. Partnerships for Health Reform/Abt Associates; 2000. Accessed August 1, 2022. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnacl100.pdf

- Willis-Shattuck M, Bidwell P, Thomas S, Wyness L, Blaauw D, Ditlopo P. Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-247

- Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(8):1255–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00094-6

- Lundgren R, Uysal J, Barker K, et al. Social Norms Lexicon. Institute for Reproductive Health/Passages Project; 2021. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://irh.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Social-Norms-Lexicon_FINAL_03.04.21-1.pdf

- Mayhew SH, Sweeney S, Warren CE, et al. Numbers, systems, people: how interactions influence integration. Insights from case studies of HIV and reproductive health services delivery in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(Suppl 4):iv67–iv81. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx097

- Winokan JY, Bogar W, Watung SR, Mandagi M. The effect of leadership style and work climate on employee performance in the population and family planning department of Manado City. Tech Soc Sci J. 2022;27(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v27i1.5548

- Bradley EH., Taylor LA., Cuellar CJ. 2015. Management matters: a leverage point for health systems strengthening in global health. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(7):411–415. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2015.101

- Prenestini A, Sartirana M, Lega F. Involving clinicians in management: assessing views of doctors and nurses on hybrid professionalism in clinical directorates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):350. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06352-0

- Management Sciences for Health (MSH). Report on Management and Leadership Development Gaps for Kenya Health Managers, Nov 2007–August 2008. MSH; 2008.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5

- Pacqué-Margolis S, Cox C, Puckett A, Schaefer L. Exploring Contraceptive Use Differentials in Sub-Saharan Africa through a Workforce Lens. Technical brief 11. CapacityPlus, IntraHealth International; 2013. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.capacityplus.org/exploring-contraceptive-usedifferentials-in-sub-saharan-africa-health-workforce-lens.html

- Macarayan EK, Ratcliffe HL, Otupiri E, et al. Facility management associated with improved primary health care outcomes in Ghana. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0218662. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218662

- Heerdegen ACS, Aikins M, Amon S, Agyemang SA, Wyss K. Managerial capacity among district health managers and its association with district performance: a comparative descriptive study of six districts in the Eastern Region of Ghana. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227974. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227974

- Catino J, Battistini E, Babchek A. Young People Advancing Sexual and Reproductive Health: Toward a New Normal. YIELD Project; 2019. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.summitfdn.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Yield_full-report_June-2019_final.pdf

- Levine R. Case Studies in Global Health: Millions Saved. Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2007.

- Awoonor-Williams JK, Sory ES, Nyonator FK, Phillips JF, Wang C, Schmitt LM. Lessons learned from scaling up a community-based health program in the Upper East Region of northern Ghana. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2013;1(1):117–133. http://dx.doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-12-00012

- Akinyemi O, Harris B, Kawonga M. Health system readiness for innovation scale-up: the experience of community-based distribution of injectable contraceptives in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):938. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4786-6

- Vision for Health System Strengthening 2030. USAID. Updated June 10, 2022. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-systems-innovation/health-systems/Vision-HSS-2030

- Foster AA, Makukula MK, Moore C, et al. Strengthening and institutionalizing the leadership and management role of frontline nurses to advance universal health coverage in Zambia. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6(4):736–746. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00067

- Argaw MD, Desta BF, Muktar SA, et al. Comparison of maternal and child health service performances following a leadership, management, and governance intervention in Ethiopia: a propensity score matched analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):862. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06873-8

- Nzinga J, Mbaabu L, English M. Service delivery in Kenyan district hospitals – what can we learn from literature on midlevel managers? Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-10

- Health Policy Project (HPP). Strengthening Women’s Capacity to Influence Health Policy Making: How Coaching Helps Translate Learning into Action. HPP; 2014. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/268_WomensLeadershipBriefFINAL.pdf

- Liu L, Desai MM, Fetene N, Ayehu T, Nadew K, Linnander E. District-level health management and health system performance: the Ethiopia Primary Healthcare Transformation Initiative. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(7):973–980. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.236

- Bose K, Martin K, Walsh K, et al. Scaling access to contraception for youth in urban slums: the Challenge Initiative’s systems-based multi-pronged strategy for youthfriendly cities. Front Glob Womens Health. 2021;2:673168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2021.673168

- Chertavian G. Gerald Chertavian quotes. BrainyQuote. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.brainyquote.com/authors/gerald-chertavian-quotes

- Linnander EL, Mantopoulos JM, Allen N, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Professionalizing healthcare management: a descriptive case study. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017;6(10):555–560. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.40

- Hartwig K, Pashman J, Cherlin E, et al. Hospital management in the context of health sector reform: a planning model in Ethiopia [published correction appears in Int J Health Plann Manage. 2009 Apr-Jun;24(2):187-90]. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2008;23(3):203–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.915

- National Training Lab (NTL). Learning Retention Pyramid. NTL; 2011.

- Chelagat T, Kokwaro G, Onyango J, Rice J. Effect of project-based experiential learning on the health service delivery indicators: a quasi-experiment study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4949-5

- Lu HS. Collaborative learning needed for healthcare management education. Int J Econ Bus Manage Res. 2020;4(9):151–161. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://ijebmr.com/uploads/pdf/archivepdf/2020/IJEBMR_615.pdf

- Adano U, Jutras M. Integration of Leadership and Management Practices into Pre-service Medical Education Curriculum: Lessons from Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Zambia. Technical brief. Leadership, Management, and Governance Project; 2017.

- Mutale W, Vardoy-Mutale AT, Kachemba A, Mukendi R, Clarke K, Mulenga D. Leadership and management training as a catalyst to health system strengthening in low-income settings: evidence from implementation of the Zambia Management and Leadership course for district health managers in Zambia. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0174536. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174536

- Chokshi H, Sethi H. From Policy to Action: Using a Capacity-Building and Mentoring Program to Implement a Family Planning Strategy in Jharkhand, India. Futures Group, Health Policy Project; 2014. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/368_ProcessDocumentationReportJharkhand.pdf

- Wheatley M. Supporting Pioneering Leaders as Communities of Practice: How to Rapidly Develop New Leaders in Great Numbers. 2002. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://margaretwheatley.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Supporting-Pioneering-Leaders-as-Communities-of-Practice.pdf

- Wenger-Trayner E, Wenger-Trayner B. Introduction to communities of practice: a brief overview of the concept and its uses. 2015. Accessed August 1, 2022. http://wengertrayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

- Gormley WJ, McCaffery J. Guidelines for Forming and Sustaining Human Resources for Health Stakeholder Leadership Groups. CapacityPlus, IntraHealth International; 2011. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.capacityplus.org/files/resources/Guidelines_HRH_SLG.pdf

- Fetene N, Canavan ME, Megentta A, et al. District-level health management and health system performance. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0210624. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210624

- Aichatou B, Seck C, Baal Anne TS, Deguenovo GC, Ntabona A, Simmons R. Strengthening government leadership in family planning programming in Senegal: from proof of concept to proof of implementation in 2 Districts. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(4):568–581. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00250

- Büyüm AM, Kenney C, Koris A, Mkumba L, Raveendran Y. Decolonising global health: if not now, when?. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(8):e003394. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003394

- Daimler, M. Three leadership skill shifts for 2021 and beyond. Forbes. November 24, 2020. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/melissadaimler/2020/11/24/the-three-leadership-skill-shiftswe-learned-in-2020/

- Landry L. Why emotional intelligence is important in leadership. Business Insights blog. April 3, 2019. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/emotionalintelligence-in-leadership

The Leading and Managing for Rights-Based Family Planning Programs brief is available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/leaders-and-managers/

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Leading and Managing for Rights-Based Family Planning Programs. Washington, DC: HIP Partnership; 2022 Aug. Available from: https://www. fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/leaders-and-managers/

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by: Maggwa Baker (USAID), Premila Bartlett (USAID), Sheri Bastien (Norwegian University of Life Sciences), Kate Henderson (MSH), Shiphrah Kuria-Ndiritu (Amref Health Africa), Madison Mellish (Palladium), Aasha Pai (Mann Global Health), and Julie Solo (Consultant).

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Maria Carrasco (USAID), Chukwuemeka Nwachukwu (USAID), Laura Raney (FP2030), and Pellavi Sharma (USAID). It was updated from a previous version published in September 2013, available here.

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/ contraception.

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

To engage with the HIPs please go to: https://www. fphighimpactpractices.org/engage-with-the-hips/.