Enabling Environment Overview

Introduction

The purpose of this overview brief is to explain the enabling environment for voluntary, rights-based family planning and how the different components of the enabling environment work together to support equitable access to and use of family planning information and services. The brief provides a framework for how the enabling environment High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs) are related among themselves and play a supporting role with the service delivery and social and behavior change (SBC) HIPs to strengthen family planning programs.

In this brief, the term “enabling environment” refers to family planning and health. In the context of health and family planning, Hardee and colleagues present the enabling environment as the governance and political, social, and economic factors that affect the overall relationship of health policies and health outcomes.1 McGinn and Connor focus on the enabling environment as the policies, programs, and community environment, coupled with social and gender norms, that work to support health systems and facilitate healthy behaviors.2 FP2020 describes the enabling environment as including the policies, laws, regulations, and funding that either help or hinder the provision of voluntary family planning services.3 The World Health Organization views the enabling environment more broadly to include the availability of necessary products and technologies, budgetary allocations and financing, and leadership and coalition-building across a range of sectors.4 Based on these experts’ insights, we can think of the enabling environment for voluntary family planning as the collection of direct and indirect factors that exert positive and negative influences on the development and implementation of family planning policies and programs and achieving family planning goals.

Enabling Environment for Family Planning: A Framework for the High Impact Practices

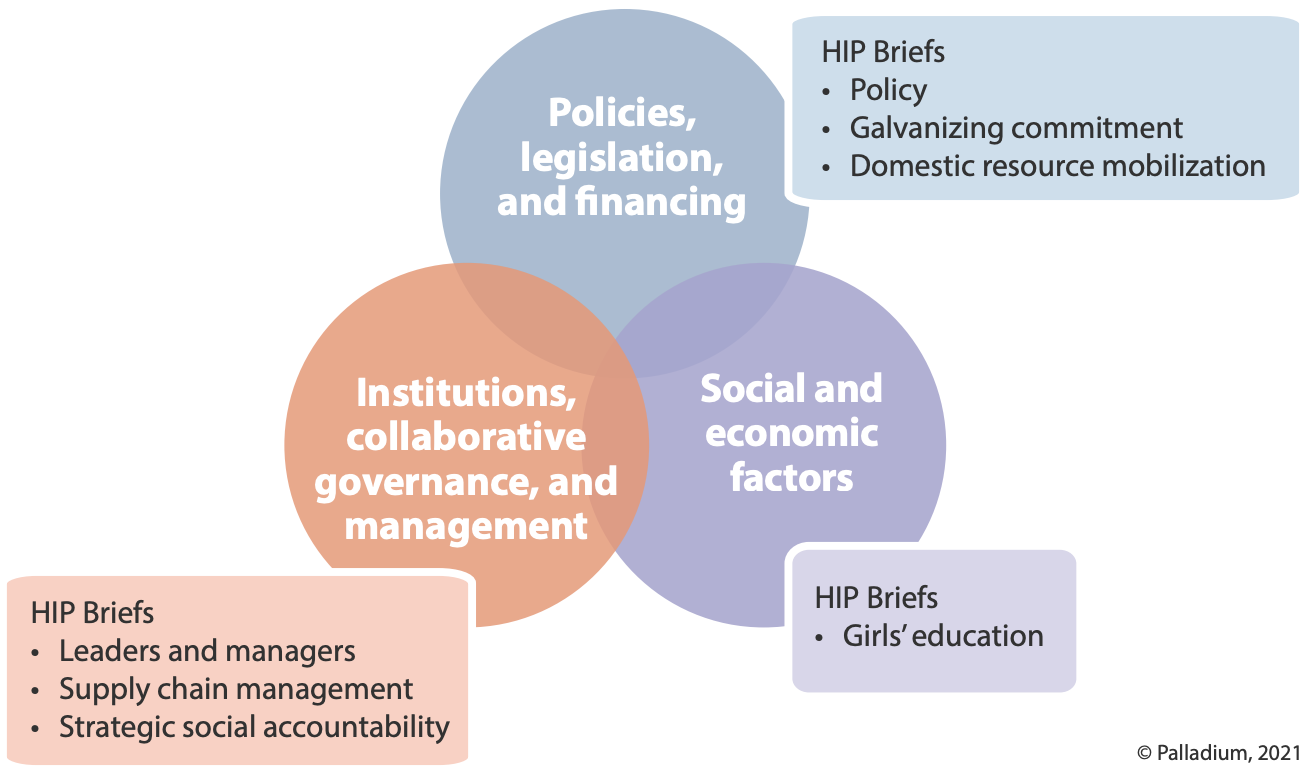

Building on the above definitions of enabling environment, for the purpose of the High Impact Practices in Family Planning, we consider the enabling environment for family planning to be a set of three interlinked groups of practices – (1) policies, legislation, financing; (2) institutions, governance, and management; and (3) social and economic factors. These three groupings are interrelated and examples of how they work together are provided below. The enabling environment HIPs refer to the conditions that, when well-functioning, facilitate an individual to make informed, voluntary decisions about family planning, and provide infrastructure to assist individuals to act on those decisions. The enabling environment HIPs, together with the service delivery and SBC HIPs, encompass the practices that together allow people to make informed choices and obtain the family planning method they want.

The following sections explain of the three groupings in the enabling environment and the high-impact practices included in each grouping. The HIPs presented here represent the current set of practices within each grouping and are not exhaustive of practices within the enabling environment that may be deemed as high impact in the future.

Policies, legislation and financing. This grouping currently includes three HIP briefs: policy, domestic public financing, and galvanizing commitment. These practices represent what is agreed upon by decision makers as to how family planning will be codified and operationalized within the government and that support or inhibit access to and use of voluntary family planning by individuals and couples. Unlike policies and domestic financing, which are linked to concrete results, commitment is more difficult to directly observe and measure, but it underpins the successful implementation of all HIPs.

Laws set out standards, procedures, and principles that governments and citizens must follow.5 Examples of how legislation has been used in family planning include: identifying funding streams, articulating citizens’ rights related to contraception, limiting commercial advertising for contraception, and addressing the importation and manufacturing of contraceptives. Country-specific experiences of family planning-related laws include the Congress of Guatemala passing a law in 2004 that required 15% of the taxes collected on alcoholic beverages be used for reproductive health; the law was later refined in 2010 to ensure that 30% of the funds be used for the purchase of contraceptive commodities. Madagascar approved a new family planning law in 2017 that reversed French colonial laws prohibiting distribution of contraception to youth or married women without spousal consent. In both cases, civil society played a critical role in advocating for the legal changes—overcoming different types of political opposition—to improve access to voluntary family planning.

Policies addressing family planning issues are more common than laws, but laws take precedence over policies and policies must adhere to laws. A policy outlines a government ministry’s goals and the approaches it will use to achieve the goals. Family planning policies often address two distinct sets of issues: (1) macro-level policies that provide high-level guidance as to how programs and services should be implemented and (2) operational policies that provide more specific guidance for implementation. Policies play an important role in ensuring equitable access and a rights-based approach to voluntary family planning to all people and especially marginalized and underserved groups, such as people with disabilities, youth, and hard-to-reach groups. They also provide a foundation for governments’ stewardship role in ensuring the public can obtain health services either though the public or private sector.

Financing for family planning is included in this grouping because financing generally exists as a result of legislative efforts and approvals, such as through an annual budget cycle. Common approaches for augmenting funding for family planning include increasing budget allocations, improving budget execution of approved budgets, increasing efficiency of expenditures, and leveraging additional sources of funding, such as through social and public insurance programs. In addition to public sector funding, the private sector can play an important role in financing through advancing a total market approach and leveraging private capital for family planning.

Institutions, collaborative governance, and management. This grouping includes three HIP briefs: leaders and managers, supply chain management, and social accountability. Institutions reflect how and where family planning is positioned within national and subnational governments. Institutions related to family planning increasingly extend beyond the health sector to include the important roles of education, planning and finance, and other sectors. Collaborative governance refers to how different stakeholders work together in consensus-oriented decision making that advances voluntary family planning issues; and management refers to the capacities needed for effective functioning of the family planning program.

Within the ministry of health, the family planning department—often housed in a family health or reproductive health division—is generally the institution responsible for leading program efforts. In many countries, a national population council plays the important role of championing family planning and population issues within the governments. Of importance also is coordination of family planning program implementation across the different levels of the health system—from national to subnational/district health to facilities.

Collaborative governance of family planning generally requires a whole-of-society engagement, including the public and private sectors, as well as citizen voices. These different sectors often work together through a national or subnational coordinating group, such as a technical working group. Given the importance of the nongovernmental and private sectors in achieving family planning goals and objectives, this type of collaborative governance structure creates a space for non-governmental organizations, faith-based organizations, and academic and research institutions—as well as donors and implementing partners—to interact. Also within collaborative governance are the accountability relationships that exist among the government, providers, and citizens, and how each dyad works together to ensure commitments are upheld.

Management refers to the capacities that program staff need for effective program operations, including program leadership and management; data systems, management, and use; commodity and supply chain management and logistics; and how programs adapt to remain responsive under strains and challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and humanitarian crises. These types of practices tend to focus on capacity strengthening of individuals and organizations, as well as through health system strengthening.

Social and economic factors. This grouping includes one HIP brief: educating girls; it also includes an evidence summary on the effect of economic empowerment on family planning use. It is somewhat different from the other two groupings because it reflects the broader forces at play that influence people’s positive and negative attitudes and behaviors around family planning.

Norms, for example, shape many aspects of individual and social behavior, including family planning use, timing and spacing of children, and adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Norms can affect the extent to which women can make decisions about a range of health-related factors, and broader issues, such as educational attainment, working outside the home, and occupational choices. Social factors may also include negative attitudes toward ethnic and sexual minority groups, religious groups, people with disabilities, or age groups—as well as different types of political opposition. Social and economic factors may have a less direct effect on the enabling environment for family planning than the other two groups of factors do; however, addressing norms and beliefs—such as through educating girls—is associated with creating a more favorable enabling environment for voluntary family planning. Economic factors also influence the enabling environment. In places with insufficient funding for family planning, out-of-pocket expenditures for family planning can put undue hardship on users with limited financial resources, which may contribute to increased unmet need and unintended pregnancies. Economic downturns in a country, such as those experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, can cause funds for family planning to be redirected to other government priorities.

Working within the enabling environment groupings. These three groupings of enabling environment HIPs (Figure 1) do not work in isolation of each other; rather, they work together in complementary ways to strengthen effective policy and program implementation. A policy or regulation may be required to establish a technical working group, and the work of the technical working group is part of the institutions and collaborative governance grouping. The working group may focus on a variety of topics, such as adolescent reproductive health, and the openness to addressing that topic is shaped by the social and economic context. Policies may exist to advance girls’ education, but without financing and political commitment, there is little chance that the policy will have the desired outcome of strengthening educational initiatives. Effective leaders and managers and a well-functioning supply chain are needed for programs to achieve the goals and objectives that have been established within policies. These examples illustrate how the three groups are interrelated and set the stage for strengthening service delivery and advancing social and behavior change.

Enabling environment practices support and leverage service delivery and SBC HIPs

The enabling environment for voluntary family planning provides the context in which family planning policies and programs are developed and implemented, and these HIPs can support the service delivery and SBC HIPs.

Service delivery of family planning is the embodiment of many family planning policies and legislation, and without political commitment and financing for family planning, services would not be provided. Services also link with institutions and collaborative governance, as the ministry of health provides technical oversight of service delivery (e.g., clinical guidelines, procurement regulations, medical eligibility criteria). Similarly, collaborative governance structures foster better coordination among the family planning stakeholders that provide oversight and implementation of programs. Strengthening leadership and management capacity is critical to the successful implementation of HIPs and family planning programmatic interventions. Without adequate financing for family planning—commodities and supplies, salaries, outreach, training, and other programmatic elements—family planning programs cannot effectively respond to the public’s reproductive health needs. Social accountability mechanisms are used to engage citizens and health sector actors to work together to improve services that meet the needs of communities.

Enabling environment HIPs also support the SBC HIPs’ socio-ecological framework, which includes the influences of organizations, communities, and the enabling environment. SBC can influence what decision makers commit to in their written/verbal expressions, the institutions they establish, and the financing they appropriate. The enabling environment includes how social and economic factors affect the uptake and use of voluntary family planning, and changes to social norms are made through implementing SBC HIPs.

These mutually reinforcing groupings of practices within the enabling environment create a space that allows family planning programs to exist and flourish, and when linked with effective service delivery practices and social and behavior change, the HIPs represent the full range of practices needed to achieve family planning outcomes, which help users achieve their fertility goals and improve health outcomes.

Tips for implementation

- Think and work politically: Much of the enabling environment happens behind the scenes, relying on evidence, relationships, and effective communication. For enabling environment work to progress, actors need to think and work politically—using political economy analysis and other tools to understand the context and develop effective responses to it, as well as being flexible and adapting to changing circumstances as policies and programs are designed and implemented. In addition, stakeholders need to understand their comparative advantages in advancing the voluntary family planning agenda and work collaboratively. The family planning financing blueprints provide examples of how stakeholders can better understand their roles in advancing different approaches to increase funding for family planning programs.

- Support participatory collaborative governance and policy processes: Because the enabling environment relies on engagement among different stakeholders, it is critical that there be space in dialogue and decision making for citizens, civil society, professional associations, and the private sector—in addition to the public sector. And within the public sector, there is the need for dialogue among the health and finance sectors, as well as among national and subnational governments. In addition, civil society has a critical role in monitoring and advocating for changes to different policy instruments and holding decision makers accountable for following through on commitments they have made.

- Use evidence to inform decision making: Evidence is key to decision making, and timely, high-quality data, information, and evidence can help ensure effective decisions are made. Evidence, which can come from policy monitoring, service statistics, survey data, supply chain data, and other sources, needs to be packaged and communicated to decision makers in effective, interpretable ways. In addition to how evidence is presented, there is also a need to encourage the use of evidence in decision making.

- Understanding processes and acting timely. Policy development generally follows a proscribed process, as does the budget cycle. Similarly, supply chain and commodity procurement follow precise steps. To support the enabling environment for family planning, stakeholders need to understand the various processes at national and subnational levels, and collaborate in developing changes and achieving improvements.

Tools and Resources

Many of the enabling environment HIPs are interrelated and the following tools can assist in different aspects of developing and implementing these practices. For more specific tools to assist with individual practices, please refer to the tool and resource section of each HIP brief.

20 Essentials on Family Planning Policy Environments is a collection of tools to help family planning program planners, implementers, decision makers, and advocates who work within and seek to understand and influence family planning policy environments. It is divided into four categories of topics: measurement and assessment tools; influencing policy environments; policy environment overviews; and policy resources on key topics.

Thinking and Acting Politically Through Applied Political Economy Analysis is a tool designed to assist stakeholders in examining power dynamics and economic and social forces that influence development. Through working to respond more rigorously to realities on the ground, PEA can help to operationalize the process of thinking politically and add significant value to strategies, projects, and activities.

Policy Implementation Assessment Tool is a tool designed to assess how well a particular policy is being implemented based on input from policymakers involved in developing the policy and stakeholders involved in its implementation. The tool considers seven aspects of policy implementation and provides adaptable questionnaires for each aspect of the policy implementation.

Voice, agency, empowerment – handbook on social participation for universal health coverage is a handbook for policymakers that addresses social and citizen participation in order to develop responsive health policies and programmes, which are more likely to be implemented by a broad stakeholder group.

References

- Hardee K, Irani L, MacInnis R, Hamilton M. Linking Health Policy With Health Systems and Health Outcomes: A Conceptual Framework. Futures Group, Health Policy Project; 2012. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/186_HealthPolicySystemOutcomesConceptualALDec.pdf

- McGinn EK, Connor HJ. The SEED Assessment Guide for Family Planning Programming. EngenderHealth; 2011. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.engenderhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/SEED-Assessment-Guide-for-Family-Planning-Programming.pdf

- Creating an enabling environment. FP2020. Accessed February 2, 2022. http://2016-2017progress.familyplanning2020.org/en/fp2020-in-countries/creating-an-enabling-environment

- World Health Organization (WHO). Consolidated Guideline on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Women Living With HIV. WHO; 2017. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254885/9789241549998-eng.pdf

- Hughes J. What is the difference between politics and law? Keystone LawStudies. March 28, 2018. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.lawstudies.com/article/what-is-the-difference-between-politics-and-law/

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Family Planning Enabling Environment Overview Brief. Washington, DC: HIP Partnership; 2022 Mar. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/enabling-environment-overview/

Acknowledgments

This brief was written by: Jay Gribble (Palladium), Beth Rottach (Palladium), and Sara Stratton (Palladium). This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical input and helpful comments: Federico Tobar (UNFPA), Marouf Balde (USAID), Davide Debende (UNFPA), Ginette Hounkanrin (Pathfinder), Anand Sinha (Packard Foundations), Saswati Das (UNFPA), John Pile (consultant), Didier Mbayi Kangudie (USAID), Baker Maggwa (USAID), Norbert Coulibaly (Ouagadougou Partnership Coordinating Unit), Jane Schueller (USAID), Zuhura Hamis Mbuguni (Ministry of Health, Tanzania), Karem Morales (Ministry of Health, Guatemala), Mary Mulombe-Phiri (Ministry of Health, Malawi), Sylvie Tidahy (Ministry of Health, Madagascar), Aminata Cisse Traore (Ministry of Health, Mali), Aoua Guindo (Ministry of Health, Mali), Kassoumou Diarra (Ministry of Health, Mali), Karen Hardee (What Works Association), Barbara Seligman (PRB), Jennie Greaney (UNFPA), Maria Carrasco (USAID), Alex Mickler (USAID), Emeka Okechukwa (USAID).

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

To engage with the HIPs please go to: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/engage-with-the-hips/