SBC Overview: Integrated framework for effective implementation of the social and behavior change high impact practices in family planning

Introduction

The purpose of this overview brief is to explain what social and behavior change (SBC) for family planning is, and why it is important in supporting individuals and couples to achieve their reproductive intentions, including their desired family size. The brief provides a framework to show how the different SBC High Impact Practices (HIPs) work together to strengthen family planning programs, and offers tips on how to choose and implement SBC programs.

SBC is an evidence-driven approach to improve and sustain changes in individual behaviors, social norms, and the enabling environment. SBC programs follow a systematic process (e.g., the P-Process or SBC Flow Chart) to design and implement interventions at the individual, community, and societal levels that support the adoption of healthy practices. These programs employ a deep understanding of human behavior that draws on theory and practice from a variety of fields, including communication, social psychology, anthropology, behavioral economics, sociology, human-centered design, and social marketing.

Evidence shows that SBC interventions are an essential component of high-quality family planning programs but remain underutilized. Investments in SBC interventions enhance those made in service delivery and policy and can be highly cost-effective. SBC interventions can be used to address a range of behavioral determinants influencing the uptake and continuation of modern contraceptive methods so that individuals and couples can achieve their reproductive intentions. These factors include social and gender roles and norms about family, sexuality, and fertility; couples’ communication and other partner-related factors; perceived personal and social costs; method-specific barriers to use (e.g., myths and misconceptions and fear of side effects); perceived low risk of getting pregnant; weak, inconsistent, or ambivalent fertility preferences; and generic disapproval of preventing pregnancy. SBC interventions also play an important role in improving client-provider interaction, improving perceptions about good quality services and trust in the health system, and reinforcing linkages with other health areas and creating a supportive normative and structural environment for family planning. As such, SBC complements the areas of service delivery and the enabling environment to create a set of interconnected HIPs that work together to strengthen family planning programs.

A Framework for the SBC HIPs

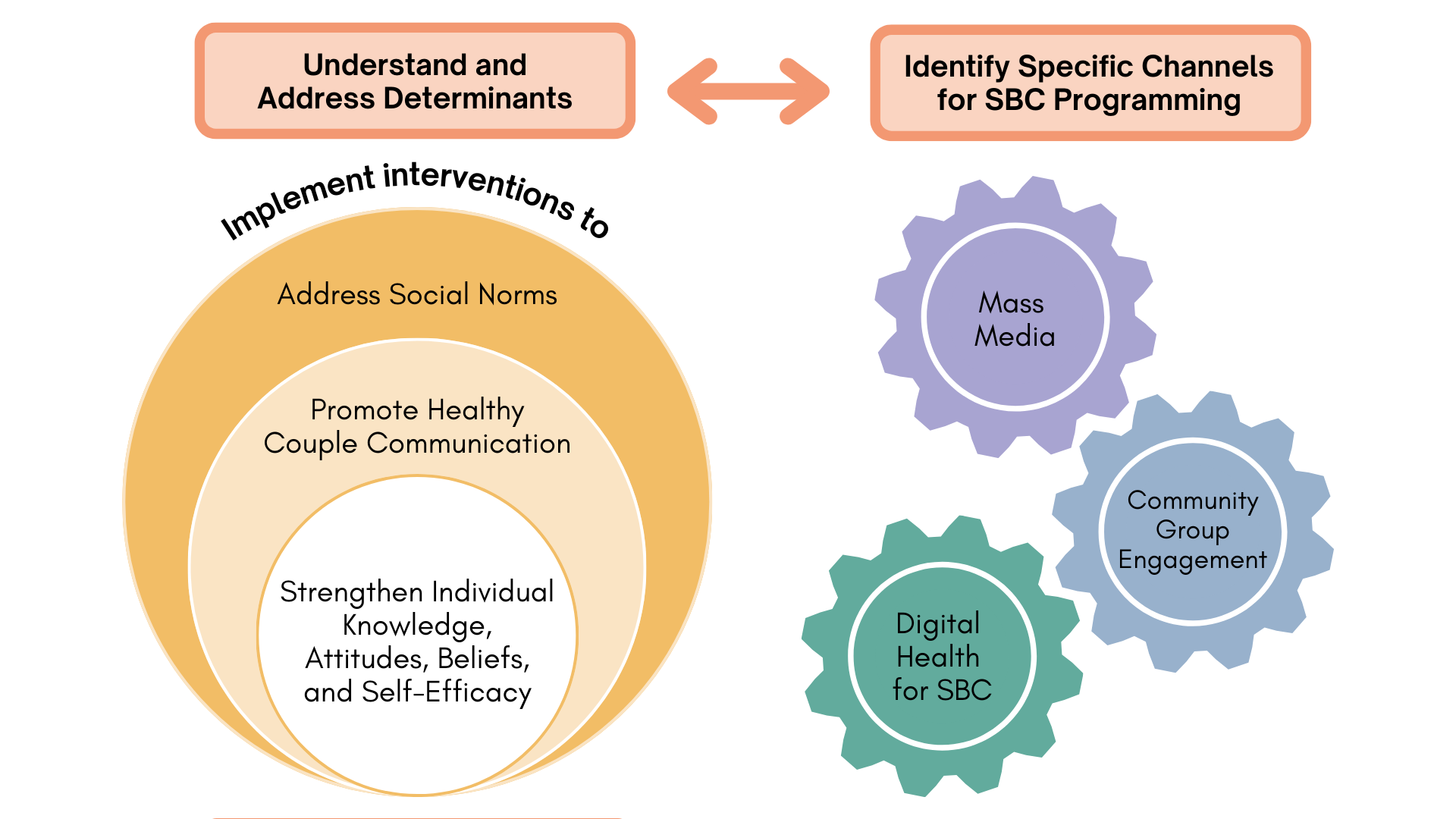

The SBC HIPs include six briefs that document proven and promising practices to help individuals and couples achieve their reproductive intentions and desired family size. These include three briefs that explain how to understand and address different determinants of family planning behavior, and three briefs that help to identify a mix of channels to reach your audience (Figure 1).

Understand and Address Determinants

Three HIP briefs outline intervention approaches that address the determinants of SBC at different levels of the social ecological model, which recognizes that determinants of health behaviors exist on multiple levels, are interrelated, and extend beyond the individual.

Specifically, socio-ecological models highlight that interpersonal relationships, community structures, and social and gender norms all influence individual choices and behaviors.

At the individual level, accurate knowledge about fertility and family planning is essential to informed choice.* Other individual factors influencing someone’s ability to reach their fertility intentions include beliefs, attitudes, and personal agency, including self-efficacy. The Knowledge, Beliefs, Attitudes, and Self-efficacy HIP brief explains the link between these individual level factors and family planning outcomes and documents SBC interventions that have been effective.

At the interpersonal level, there are various forms of communication that influence family planning use, e.g., between peers; parent or trusted adult to adolescent; and provider to client. Couples’ communication and joint decision making, which are influenced by gender roles and norms, are particularly important in the voluntary uptake of contraceptive methods. The Promoting Healthy Couples’ Communication to Improve Reproductive Health Outcomes HIP brief establishes the evidence linking couples’ communication to family planning and reproductive health outcomes, and documents evidence from numerous studies that describe the role of SBC interventions in facilitating this critical behavior.

At the community level, social and gender norms—or the perceived informal, mostly unwritten, rules that define acceptable, appropriate, and obligatory behaviors within a given community or group, including those based on gender—influence an individual’s or couple’s desire for, and access to, family planning methods. The Social Norms HIP brief describes the evidence from interventions that use reflective dialogue, interpersonal communication, mass and/or social media, digital technologies, or a combination of these channels to fortify or shift social norms to increase social support for voluntary family planning. While social norms are context specific, and manifest differently across country and community contexts, this evidence base is informative when creating interventions adapted to the context and intended audience.

*Informed choice emphasizes that family planning clients select the method that best satisfies their personal, reproductive and health needs, based on a thorough understanding of their contraceptive options.1

Identify Intervention Options

SBC interventions to address behavioral determinants can use a variety of communication channels and other intervention approaches. Currently, there are three HIPs that address specific communication channels for SBC: mass media, community group engagement (CGE), and digital technologies. Other SBC approaches can also be leveraged.

Mass media programming in reproductive health can influence individual behaviors by providing accurate information, building self-efficacy, and promoting attitudes and social norms that support healthy reproductive behaviors. Many of the most effective mass media SBC programs are based on social learning and related theories, which emphasize the role of observation and social comparison processes in building motivation and self-efficacy to perform specific behaviors.2 For example, role models in media (e.g., characters in stories) are often employed to show audiences how someone may navigate their contraceptive journey—how they deal with setbacks and overcome personal, social, and other challenges—to achieve their desired goals. The Mass Media HIP brief describes the evidence on, and experience with, mass media programming in family planning. The distinguishing characteristic of mass media programs, relative to other SBC interventions, is that they can reach a large audience—often national in scope— with consistent, high-quality messages, primarily through TV and radio (e.g., public service announcements or advertisements, talk shows, or serial dramas).

CGE interventions typically follow a defined process to identify and respond to perceived community and social drivers of, and barriers to, family planning and reproductive health behaviors. CGE interventions may include activities such as reflective dialogues, mapping exercises, exploratory games, community theater, and/or prioritization exercises.

Although activities may be facilitated by outsiders, such as NGO staff, public servants, or extension workers, they rely on active participation of local community groups and members to build collective efficacy, expand critical consciousness, and catalyze community and social change. The Community Group Engagement HIP brief shares evidence from such interventions that work with and through community groups to influence individual behaviors and/or social norms.

Digital technologies and social media have the potential to provide accurate information to individuals when and where they need it, often with the benefit of anonymity and confidentiality. Making information available through digital applications may also reduce the time and cost related to seeking or receiving information through more traditional sources, such as print or interpersonal communication (including counseling). Furthermore, it shows that digital interventions can be used to shift perceived norms around family planning.3 The Digital Health for Social and Behavior Change HIP brief outlines the evidence for this promising practice and provides tips on how to implement digital interventions for family planning programs. Digital technologies are relatively new, and evidence is emerging to guide programs on how to best utilize digital technologies to achieve family planning outcomes.

While these briefs outline the evidence for each specific channel, SBC programs are most effective when they use a multi-channel approach, and there is consistent evidence that shows the greater the exposure to SBC campaigns through different channels, the greater the odds of behavior change (known as a dose-response relationship). Because of this, SBC programs often employ multiple channels and approaches to reach the broad range of people who may influence use of family planning—women and girls, men and boys, partners and family members, community and religious leaders, facility- and community-based health providers, and so on. Program designers and implementers should carefully consider which approaches and channels will be most likely to be effective given their particular context and the preferences of their target audience(s).

SBC practices support and enhance service delivery and enabling environment HIPs. SBC approaches can support service delivery interventions before, during, and after a client-provider interaction. Before a client seeks out family planning and reproductive health services, SBC approaches are important to increase awareness of, and interest in, family planning; foster supportive social norms; and create a supportive enabling environment.

During service delivery, SBC approaches can be used to empower clients, improve provider behavior, and build trust. After a client leaves a clinic, SBC can enhance follow-up, support behavioral maintenance, and reinforce health and cross-sectoral linkages.† Specifically, SBC approaches can be used to support community health workers through job aids and counseling skills to help dispel rumors and address social barriers to family planning; promote postpartum and postabortion family planning by addressing myths and misconceptions around modern contraceptive methods; create behavioral-based job aids for pharmacies and drug shops, and contribute to effective social marketing through the design of communication messages to improve knowledge, attitudes, and use of family planning products.

SBC approaches are also an important tool in creating an enabling environment for family planning, including for adolescents and ensuring equitable access to high-quality family planning information and services. They can be used to help address social and economic factors, such as educating girls, by shaping social norms that support girls’ education. SBC approaches can also be used to support high-performing institutions, better governance, and management of programs. For example, SBC programs are a helpful tool in promoting social accountability by bringing together community members with health workers and local officials to establish common goals. Lastly, SBC approaches can be leveraged to galvanize commitment and create supportive laws, policies, and financing for family planning.

†For further guidance and implementation examples see the Circle of Care Model.4

Tips for Implementation

- Use formative research based on theoretical models to guide which determinant to address. It is important to match the intervention level (e.g. individual, relational, social) to the level of the determinant that is most influencing the health outcome. For example, if social norms are a critical barrier to desired family planning behaviors, an intervention focused on individual knowledge is not likely to result in significant behavioral change. Remember, though, that the different levels of influence in the social ecological model are closely interrelated, and the evidence shows that the most successful SBC interventions are often those that address these multiple layers of influence simultaneously. Behavioral theories can be useful tools to help identify measurable determinants of family planning behaviors and inform selection of programmatic approaches.

- Ensure early and frequent pretesting of materials, messages, and approaches to ensure that programs are designed with the full input of the intended audience and their Pretesting measures the reaction of the selected group of individuals and helps determine whether the priority audience will find the components understandable, believable, and appealing. Pretesting gathers information about whether the messages are clear and understood, whether the materials and language are acceptable, that they are relevant to the intended audience, and whether any calls to action actually inspired the audience to act. There are several approaches to pretesting such as conducting focus group discussions or holding interviews with the target audience. No matter which approach is used, frequent pretesting with the target audience early in the design process can help to inform rapid iterations of solutions before implementation.

- Select channels to meet the target audience and objectives based on formative Choose the channels and options that have proven to work, that formative research has shown will most effectively reach and engage your target audience, and that are within the available budget. Mass media may include messaging to increase knowledge (e.g., providing information about family planning in a short TV spot), promote couples’ communication (through role modeling in a serial drama or call to action in a TV spot), and shift social norms (using long-format serial dramas and supported by community group engagement). On the other hand, digital SMS messages may be useful to increase individual knowledge (e.g., providing method-specific information), or remind users to take a specific action, but are less likely to impact social norms. Formative research can also guide you in understanding which channels of information people trust or need. Ideally, seek to use a range of approaches to reach audiences in a coordinated manner, creating a “surround sound” effect so that the audience receives messages through multiple channels over a defined period of time, and each channel reinforces the others to strengthen the overall salience and impact of the key messages. The NURHI 2 project provides a good example of how a transmedia approach can be used to spread a message across multiple media platforms.5,6

- Work with existing community groups and communication platforms. Ensure that the budget and timeline are adequate to engage a diverse range of community members. Using existing social infrastructure (e.g., religious organizations, youth or women’s groups, and/or popular radio programs) encourages sustainability and increases the potential for scale-up. It can also help to ensure that interventions are culturally appropriate and locally driven. This approach leverages the existing relationships and trust that those platforms offer. Programs should, however, intentionally include vulnerable and/or marginalized populations that might be commonly excluded from existing groups.

- Segment audiences into subgroups based on demographic, psychographic, life stage, and/ or behavioral factors and tailor interventions accordingly. Segmentation can help to identify and prioritize the potential for behavior change among a specific group and SBC programs can then tailor services and shape communication efforts accordingly.7 Effective segmentation recognizes that behavior change may vary between specific subgroups that have, or are perceived to have, similar characteristics and that different groups will respond differently to SBC approaches. For example, audience segmentation can help to identify potential family planning users who face a specific barrier to uptake— such as those with a desire to avoid or delay pregnancy but who are influenced by myths and misconceptions about modern contraceptive methods. Segmentation can also help identify audiences who are facing key life moments, such as marriage or the birth of a first child, where they are more open to new ideas and information, including discussion on family planning.

- Intentionally incorporate equity and the social determinants of health into SBC programs for family planning.8 Economic, social, and environmental factors can lead to inequities in family planning programs. As such, SBC programs should take into account opportunities and approaches that they can leverage to contribute to more equitable outcomes. This may include meaningful engagement with communities to ensure programs are driven by community needs and values, long-term multisectoral partnerships to address social determinants of health, intentionally addressing equal access to information and services provided by the SBC program, and using an intersectional gender lens to analyze and address the specific social determinants of health that disadvantage specific subgroups.

- Use a gender-synchronized approach in SBC programs for family planning.9 It is important to ensure that SBC programs that engage men and/ or boys maintain a gender transformative and gender-synchronized approach—that is, they are working with both men and women, girls and boys to ensure that interventions are mutually reinforcing and outcomes do not reinforce inequitable power dynamics.10 Family planning and reproductive health are important parts of the lives of all people, regardless of gender. Evidence shows that engaging men and boys in family planning programs can decrease unintended pregnancy. However, programs that pay limited or no attention to gender and power dynamics can reinforce existing inequitable decision making and power structures that reduce the agency of women and girls to make family planning decisions.

- Design and use monitoring and evaluation methodologies to assess the impact of interventions and make real-time adjustments to programming.11 To ensure that SBC programs are being implemented as designed, and are having the intended impact, SBC programs should systematically include SBC measurement tools and indicators in monitoring and evaluation.12 Consider the use of social listening approaches, which can be an important tool for collecting information about target audiences’ knowledge and attitudes, as well as their exposure and responses to social media interventions.13 When designing and monitoring programs for adolescents and youth, it is important to ensure that evaluation methodologies are appropriate for their needs. This type of SBC data can be used to monitor program quality and efficiency, improve program implementation, and advocate for further investment.

Additional tips for implementation are provided in each of the HIP briefs.

Tools and Resources

The SBC HIPs are interrelated and the following tools can assist in different aspects of developing and implementing these practices. For more specific tools to assist with individual practices, please see the tools and resources section of each HIP brief.

- The Business Case for Investing in Social and Behavior Change for Family Planning. The Business Case uses an evidence-based approach to answer questions about the effectiveness, cost- effectiveness, and return on investment of SBC in family planning.

- The Behavioural Drivers Model: A Conceptual Framework for Social and Behaviour Change Programming. The Behavioural Drivers Model can be used as a basis to conduct participatory situational assessments, design and operationalize strategies and programmes, monitor interventions, and evaluate effectiveness.

- The Compass for SBC. The Compass is a curated collection of SBC resources that offers the highest quality “how-to” tools and packages of materials from SBC It is designed to help SBC professionals improve their work by providing practical resources.

- Behavior Change Impact. Behavior Change Impact is a collection of databases, as well as accompanying reports, briefs, factsheets, and infographics, that provide program planners, implementers, and policy makers with the evidence they need to make the case for the value of SBC and to strengthen the impact of their SBC efforts.

- C-Modules. C-Modules are a six-module learning package for facilitated, face-to-face workshops on social and behavior change communication. Designed for communication practitioners in small- and medium-sized development organizations.

- Social and Behavior Change Indicator Bank for Family Planning and Service Delivery. The family planning indicator bank is a collection of sample indicators specifically for use in SBC programs that provides illustrative quality indicators specifically for global programs using SBC approaches to address FP challenges.

- A Short Guide to Social and Behavior Change (SBCC) Theory and Models. This PowerPoint presentation provides background on the theories and models commonly used in SBC programs.

References

- Kim YM, Kols A, Mucheke S. Informed choice and decision-making in family planning counseling in Int Fam Plann Persp. 1998;24(1):4–11, 42.

- Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3). Social Learning Theory: An HC3 Research Primer. HC3; 2014. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://www. org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/ SocialLearningTheory.pdf

- Castle S, Silva M. Family Planning and Youth in West Africa: Mass Media, Digital Media, and Social and Behavior Change Communication Strategies. Breakthrough RESEARCH Literature Review. Population Council; 2019. Accessed August 10, 2022. https:// breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/ uploads/2019/09/Mass-Media-Literature-Review.pdf

- Circle of Care Breakthrough ACTION. 2021. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/circle-of-care-model/

- Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI 2). Transmedia: Scripting, Production and Effect on Ideation. NURHI 2; 2015. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://www.nurhi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ Transmedia-Scripting-Production-and-Effect-on-Ideation. pdf

- Higgs ES, Goldberg AB, Labrique AB, et al. Understanding the role of mHealth and other media interventions for behavior change to enhance child survival and development in low- and middle-income countries: an evidence J Health Commun. 2014;19 (Suppl 1):164–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.929763

- Advanced audience segmentation for social and behavior Breakthrough ACTION. Updated September 2021. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://thecompassforsbc.org/how-to-guides/advanced-audience- segmentation-social-and-behavior-change

- Breakthrough Intentionally Incorporating the Social Determinants of Health into Social and Behavior Change Programming for Family Planning: A Technical Report. Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs; 2022. Accessed August 10, 2022. https:// breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/01/Intentionally-Incorporating-SDOH- into-SBC-Programming-for-FP.pdf

- Greene ME, Perlson SM. Gender synchronization: updating and expanding the concept. Presented at: 2016 IGWG Plenary; October 26, 2016; Washington, Accessed August 10, 2022. https://www.igwg.org/ wp-content/uploads/2017/06/IGWG_Plenary2016_ GenderSynch_Greene.pdf

- Breakthrough Know, Care, Do: A Theory of Change for Engaging Men and Boys in Family Planning. Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs; 2021. Accessed August 10, 2022. https:// breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Know-Care-Do-Engaging-Men-Boys.pdf

- Dougherty L, Silva M, Spielman K. Strengthening Social and Behavior Change Monitoring and Evaluation for Family Planning in Francophone West Africa. Breakthrough RESEARCH Final Report. Population Council; 2020. Accessed August 10, 2022. https:// org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/BR_WABA_FP_IndicMap_Report.pdf

- Breakthrough RESEARCH. Twelve Recommended SBC Indicators for Family Planning. Population Council; Accessed August 10, 2022. https:// breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/ uploads/2020/11/BR_SBCInd_Brief.pdf

- Breakthrough RESEARCH. Informing Social and Behavior Change Programs Using Social Listening and Social Monitoring. Population Council; 2020. Accessed August 10, https://breakthroughactionandresearch. org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/BR_Brief_SocList_ Mntrng.pdf

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). SBC Overview: Integrated Framework for Effective Implementation of the Social and Behavior Change High Impact Practices in Family Planning. Washington, DC: HIP Partnership; 2022 August. Available from: https://www. fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/sbc-overview/

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: This brief was written by: Maria A. Carrasco (USAID) and Joanna Skinner (JHU).

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Sonja Caffe (PAHO), Norbert Coulibaly (Ouagadougou Partnership Coordinating Unit), Richard Fitton (British Medical Association), Chris Gallavotti (BMGF), Jill Gay (What Works Association), Xaher Gul (Breakthrough RESEARCH), Kamden Hoffmann (MIHR), Nrupa Jani (Breakthrough RESEARCH), Gael O’Sullivan (Kantar Public), Alice Payne Merritt (JHU), Lucy Wilson (Consultant). It was updated from a previous version published in April 2018, available here.

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/ health-topics/contraception.

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

To engage with the HIPs please go to: https://www. fphighimpactpractices.org/engage-with-the-hips/.